What are parentheses used for? Again there are parentheses, and in the parentheses there is gossip. Parentheses in periodic decimals

The word "brackets" in English is translated as or parentheses.

Parentheses are used to separate a word or phrase from the rest of the sentence. They are often used to describe something in a sentence that the writer has not yet mentioned.

The most commonly used parentheses ( round brackets - ()) and square brackets ( square brackets).

Parentheses are always used in pairs and their purpose is to add necessary information without breaking the main sentence, in such a way that if you remove the words in brackets, the sentence remains intact.

Round Brackets ()

Unlike square brackets, information enclosed in parentheses is part of a sentence, but does not convey the main meaning.

Example:

When he saw Sally (a girl he used to go to school with) in the shop, he could not believe his eyes.

Some grammarians believe that (whenever possible) we should use commas.

My car is in the drive (with the window open).

I just had an accident with our new car. (Sssh! My husband doesn’t know yet.)

The weather is wonderful. (If only it were always like this!)

The party was fantastic (as always)!

As you can see, the information in brackets is not an integral part of the sentence and its meaning will not change if the information in brackets is removed. Thus, parentheses can be perceived as a temporary interruption of a sentence in writing.

In many cases, a pair of commas or hyphens can replace parentheses:

When he saw Sally, a girl he used to go to school with, in the shop, he could not believe his eyes.

When he saw Sally — a girl he used to go to school with — in the shop, he could not believe his eyes.

However, such a replacement is appropriate only when the additional sentence, which is interspersed into the main one, has a direct connection with the main sentence.

It is considered good manners Not use long sentences in brackets because this can make the sentence difficult to understand.

For this reason, try to use parentheses as little as possible, especially when the closing parenthesis occurs at the end of a sentence. The period is always placed after the closing parenthesis.

The train will call at Gillingham (Kent) and Rainham (Kent) .

Square Brackets

As opposed to parentheses, square brackets are typically used to enclose text that explains something not directly related to the main sentence.

For example:

I love dark chocolate.

"Pronoun", "verb", "adjective" and "noun" are explanatory words, they are not part of the sentence "I love dark chocolate" and therefore must be clearly separated from the main words of the sentence using square brackets.

Another example of the use of square brackets is in quotations, when the words do not relate to the quote itself, but are included in it as explanatory words.

“According to John, he said he ‘couldn’t believe it when he saw her as they used to go to school together.’ He was very surprised to see her after all these years.”

Square brackets are for informational purposes, but are not the main part of the quotation.

Video in English with tips on using brackets in writing.

Video clip with a rap song prepared by a student for a lesson English language. The song talks about parentheses in English in verse.

English Joke

A seaman meets a pirate in a bar, and talk turns to their adventures on the sea. The seaman notes that the pirate has a peg-leg, a hook, and an eye patch.

The seaman asks, "So, how did you end up with the peg-leg?"

The pirate replies, “We were in a storm at sea, and I was swept overboard into a school of sharks. Just as my men were pulling me out, a shark bit my leg off.”

"Wow!" said the seaman. "What about your hook?"

“Well,” replied the pirate, “We were boarding an enemy ship and were fighting the other sailors with swords. One of the enemy cut my hand off."

"Incredible!" remarked the seaman. "How did you get the eye patch?"

"A seagull dropping fell into my eye," replied the pirate.

"You lost your eye to a seagull dropping?" the sailor asked incredulously.

“Well,” said the pirate, “it was my first day with my hook.”

In this article we will talk about parentheses in mathematics, let’s figure out what types of them are used and what they are used for. First, we will list the main types of brackets, introduce their designations and terms that we will use when describing the material. After that, let's move on to specifics and use examples to understand where and what brackets are used.

Page navigation.

Basic types of brackets, notation, terminology

Several types of brackets have been used in mathematics, and they, of course, have acquired their own mathematical meaning. Mainly used in mathematics three types of brackets: parentheses matched by ( and ) , square [ and ] , and curly braces ( and ) . However, there are also other types of brackets, for example, backsquare ] and [, or angle brackets and > .

Parentheses in mathematics are mostly used in pairs: an open parenthesis (with a corresponding closing parenthesis), an open square bracket [with a closing square bracket], and finally an open curly brace (and a closing curly brace). But there are also other combinations of them, for example, ( and ] or [ and ) . Paired brackets enclose a mathematical expression and force it to be viewed as a structural unit, or as part of some larger mathematical expression.

As for unpaired brackets, the most common ones are a single curly bracket of the form ( , which is a system sign and denotes the intersection of sets, as well as a single square bracket [ , denoting the union of sets.

So, having decided on the designations and names of the brackets, we can move on to the options for their use.

Parentheses to indicate the order of actions

One of the purposes of parentheses in mathematics is to indicate the order in which actions are performed or to change the accepted order of actions. For these purposes, parentheses are generally used in pairs, enclosing an expression that is part of the original expression. In this case, you should first perform the actions in brackets according to the accepted order (first multiplication and division, and then addition and subtraction), and then perform all other actions.

Let's give an example that explains how to use parentheses to explicitly indicate which actions need to be performed first. The expression without parentheses 5+3−2 implies that first 5 is added to 3, after which 2 is subtracted from the resulting sum. If you put parentheses in the original expression like this (5+3)−2, then nothing will change in the order of actions. And if the brackets are placed as follows 5+(3−2) , then you should first calculate the difference in the brackets, then add 5 and the resulting difference.

Now let’s give an example of setting parentheses that allow you to change the accepted order of actions. For example, the expression 5 + 2 4 implies that first the multiplication of 2 by 4 will be performed, and only then the addition of 5 will be performed with the resulting product of 2 and 4. The expression with brackets 5+(2·4) assumes exactly the same actions. However, if you put the brackets like this (5+2)·4, then you will first need to calculate the sum of the numbers 5 and 2, after which the result will be multiplied by 4.

It should be noted that expressions may contain several pairs of parentheses indicating the order in which actions are performed, for example, (4+5 2)−0.5:(7−2):(2+1+12). In the written expression, the actions in the first pair of brackets are performed first, then in the second, then in the third, after which all other actions are performed in accordance with the accepted order.

Moreover, there can be parentheses within parentheses, parentheses within parentheses within parentheses, and so on, for example, and . In these cases, the actions are performed first within the inner brackets, then within the brackets containing the inner brackets, and so on. In other words, actions are performed starting from the inner brackets, gradually moving towards the outer brackets. So the expression ![]() implies that the actions in the inner brackets will be performed first, that is, the number 3 will be subtracted from 6, then 4 will be multiplied by the calculated difference and the number 8 will be added to the result, so the result in the outer brackets will be obtained, and finally the resulting result will be divided by 2.

implies that the actions in the inner brackets will be performed first, that is, the number 3 will be subtracted from 6, then 4 will be multiplied by the calculated difference and the number 8 will be added to the result, so the result in the outer brackets will be obtained, and finally the resulting result will be divided by 2.

In writing, brackets of different sizes are often used, this is done in order to clearly distinguish internal brackets from external ones. In this case, inner brackets are usually used smaller than outer ones, for example,  . For the same purposes, sometimes pairs of brackets are highlighted in different colors, for example, (2+2· (2+(5·4−4) )·(6:2−3·7)·(5−3). And sometimes, pursuing the same goals, along with parentheses, they use square and, if necessary, curly brackets, for example, ·7 or {5++7−2}:

.

. For the same purposes, sometimes pairs of brackets are highlighted in different colors, for example, (2+2· (2+(5·4−4) )·(6:2−3·7)·(5−3). And sometimes, pursuing the same goals, along with parentheses, they use square and, if necessary, curly brackets, for example, ·7 or {5++7−2}:

.

In conclusion of this point, I would like to say that before performing actions in an expression, it is very important to correctly parse the parentheses in pairs indicating the order in which the actions are performed. To do this, arm yourself with colored pencils and start going through the brackets from left to right, marking them in pairs according to the following rule.

As soon as the first closing parenthesis is found, it and the opening parenthesis closest to it to the left should be marked with some color. After this, you need to continue moving to the right until the next unmarked closing bracket. Once it is found, you should mark it and the closest unmarked opening parenthesis with a different color. And so on, continue moving to the right until all brackets are marked. To this rule we just need to add that if there are fractions in the expression, then this rule must be applied first to the expression in the numerator, then to the expression in the denominator, and then move on.

Negative numbers in brackets

Another purpose of parentheses is revealed when expressions with them appear and need to be written. Negative numbers in expressions are enclosed in parentheses.

Here are examples of entries with negative numbers in brackets: 5+(−3)+(−2)·(−1) ,  .

.

As an exception negative number is not enclosed in parentheses when it is the first number from the left in an expression, or the first number from the left in the numerator or denominator of a fraction. For example, in the expression −5·4+(−4):2 the first negative number −5 is written without parentheses; in the denominator of the fraction ![]() The first number from the left, −2.2, is also not enclosed in parentheses. Notations with brackets of the form (−5)·4+(−4):2 and

The first number from the left, −2.2, is also not enclosed in parentheses. Notations with brackets of the form (−5)·4+(−4):2 and ![]() . It should be noted here that notations with brackets are more strict, since expressions without brackets sometimes allow different interpretations, for example, −5 4+(−4):2 can be understood as (−5) 4+(−4): 2 or as −(5·4)+(−4):2. So, when composing expressions, you should not “strive for minimalism” and do not put the negative number on the left in brackets.

. It should be noted here that notations with brackets are more strict, since expressions without brackets sometimes allow different interpretations, for example, −5 4+(−4):2 can be understood as (−5) 4+(−4): 2 or as −(5·4)+(−4):2. So, when composing expressions, you should not “strive for minimalism” and do not put the negative number on the left in brackets.

Everything said in this paragraph above also applies to variables, powers, roots, fractions, expressions in brackets and functions preceded by a minus sign - they are also enclosed in parentheses. Here are examples of such records: 5·(−x) , 12:(−2 2) , ![]() , .

, .

Parentheses for expressions with which actions are performed

Parentheses are also used to indicate expressions with which some action is carried out, be it raising to a power, taking a derivative, etc. Let's talk about this in more detail.

Parentheses in expressions with powers

An expression that is an exponent does not have to be placed in parentheses. This is explained by the superscript notation of the indicator. For example, from the notation 2 x+3 it is clear that 2 is the base, and the expression x+3 is the exponent. However, if the degree is denoted using the ^ sign, then the expression relating to the exponent will have to be placed in parentheses. In this notation, the last expression will be written as 2^(x+3) . If we didn't put the parentheses when we wrote 2^x+3, it would mean 2 x +3.

The situation is slightly different with the basis of the degree. It is clear that it makes no sense to put the base of the degree in brackets when it is zero, natural number or any variable, since in any case it will be clear that the exponent refers specifically to this base. For example, 0 3, 5 x 2 +5, y 0.5.

But when the basis of the degree is fractional number, a negative number or some expression, then it must be enclosed in parentheses. Let's give examples: (0.75) 2 , , ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

If you do not put in brackets the expression that is the base of the degree, then you can only guess that the exponent refers to the entire expression, and not to its individual number or variable. To explain this idea, let’s take a degree whose base is the sum x 2 +y, and the indicator is the number -2; this degree corresponds to the expression (x 2 +y) -2. If we did not put the base in brackets, the expression would look like this x 2 +y -2, which shows that the power -2 refers to the variable y, and not to the expression x 2 +y.

In conclusion of this paragraph, we note that for degrees whose bases are trigonometric functions or, and the indicator is, a special form of recording is adopted - the indicator is written after sin, cos, tg, ctg, arcsin, arccos, arctg, arcctg, log, ln or lg. For example, we give the following expressions sin 2 x, arccos 3 y, ln 5 e and. These notations actually mean (sin x) 2 , (arccos y) 3 , (lne) 5 and . By the way, the last entries with bases enclosed in brackets are also acceptable and can be used along with those indicated earlier.

Parentheses in expressions with roots

There is no need to enclose expressions under the radical (()) in parentheses, since its leading character serves their role. So the expression essentially means.

Parentheses in expressions with trigonometric functions

Negative numbers and expressions related to or often need to be enclosed in parentheses to make it clear that the function is being applied to that expression and not to something else. Here are examples of entries: sin(−5) , cos(x+2) ,  .

.

There is one peculiarity: after sin, cos, tg, ctg, arcsin, arccos, arctg and arcctg it is not customary to write numbers and expressions in parentheses if it is clear that the functions are applied to them and there is no ambiguity. So it is not necessary to enclose single non-negative numbers in brackets, for example, sin 1, arccos 0.3, variables, for example, sin x, arctan z, fractions, for example,  , roots and powers, for example, etc.

, roots and powers, for example, etc.

And in trigonometry, multiple angles x, 2 x, 3 x, ... stand out, which for some reason are also not usually written in parentheses, for example, sin 2x, ctg 7x, cos 3α, etc. Although it is not a mistake, and sometimes it is preferable, to write these expressions with parentheses to avoid possible ambiguities. For example, what does sin2 x:2 mean? Agree, the notation sin(2 x): 2 is much clearer: it is clearly visible that two x are related to the sine, and the sine of two x is divisible by 2.

Parentheses in expressions with logarithms

Numerical expressions and expressions with variables with which logarithm is carried out are enclosed in parentheses when written, for example, ln(e −1 +e 1), log 3 (x 2 +3 x+7), log((x+ 1)·(x−2)) .

You can omit the use of parentheses when it is clear to which expression or number the logarithm is applied. That is, it is not necessary to put parentheses when the sign of the logarithm is positive number, fraction, degree, root, some function, etc. Here are examples of such entries: log 2 x 5 , , .

Brackets within

Parentheses are also used when working with . Under the limit sign, you need to write in parentheses expressions that represent sums, differences, products, or quotients. Here are some examples:  And .

And .

You can omit the brackets if it is clear which expression the limit sign lim refers to, for example, and .

Parentheses and derivative

Parentheses have found their use when describing a process. So the expression is taken into brackets, followed by the sign of the derivative. For example, (x+1)’ or  .

.

Integrands in parentheses

Parentheses are used in . An integrand representing a certain sum or difference is placed in parentheses. Here are some examples: .

Parentheses separating a function argument

In mathematics, parentheses have taken their place in denoting functions with their own arguments. So the function f of the variable x is written as f(x) . Similarly, the arguments of functions of several variables are listed in parentheses, for example, F(x, y, z, t) is a function F of four variables x, y, z and t.

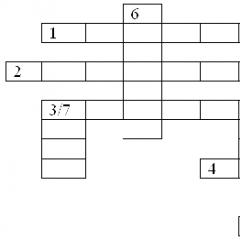

Parentheses in periodic decimals

To indicate the period in, it is customary to use parentheses. Let's give a couple of examples.

In the periodic decimal fraction 0.232323... the period is made up of two digits 2 and 3, the period is enclosed in parentheses, and is written once from the moment it appears: this is how we get the entry 0,(23). Here's another example of a periodic decimal fraction: 5.35(127) .

Parentheses to denote numeric intervals

For designation, pairs of brackets of four types are used: () , (] , [) and . Inside these brackets, two numbers are indicated, separated by a semicolon or comma - first the smaller one, then the larger one, limiting the numerical interval. A parenthesis adjacent to a number means that the number is not included in the gap, and a square bracket means that the number is included. If the gap is associated with infinity, then a parenthesis is placed with the infinity symbol.

For clarification, we give examples of numerical intervals with all types of brackets in their designation: (0, 5) , [−0.5, 12) ,  ,

, (−∞, −4]

, (−3, +∞)

, (−∞, +∞)

.

,

, (−∞, −4]

, (−3, +∞)

, (−∞, +∞)

.

In some books you can find notations for numerical intervals in which instead of a parenthesis (a back square bracket ] is used, and instead of a bracket) a bracket [ is used. In this notation, the notation ]0, 1[ is equivalent to the notation (0, 1) . Similar to 0, 1] the entry (0, 1] corresponds.

Designations for systems and sets of equations and inequalities

To write , as well as systems of equations and inequalities, use a single curly brace of the form ( . In this case, equations and/or inequalities are written in a column, and on the left they are bordered by a curly brace.

Let us show with examples how the curly brace is used to denote systems. For example,  - a system of two equations with one variable, - a system of two inequalities with two variables, and

- a system of two equations with one variable, - a system of two inequalities with two variables, and  - a system of two equations and one inequality.

- a system of two equations and one inequality.

The curly brace of a system means intersection in the language of sets. So the system of equations is essentially the intersection of the solutions of these equations, that is, all general solutions. And to denote a union, a collection sign is used in the form of a square bracket rather than a curly one.

So, sets of equations and inequalities are denoted similarly to systems, only instead of a curly bracket, a square [ is written. Here are a couple of examples of recording aggregates:  And .

And .

Often systems and aggregates can be seen in one expression, for example, .

Curly brace to indicate a piecewise function

In the notation piecewise function A single curly brace is used; this brace contains function-defining formulas indicating the corresponding numeric intervals. As an example illustrating how a curly brace is written in the notation of a piecewise function, we can give the modulus function:  .

.

Brackets to indicate the coordinates of a point

Parentheses are also used to indicate the coordinates of a point. The coordinates of points on, in the plane and in three-dimensional space, as well as the coordinates of points in n-dimensional space, are written in parentheses.

For example, the notation A(1) means that point A has coordinates 1, and the notation Q(x, y, z) means that point Q has coordinates x, y and z.

Brackets for listing elements of a set

One way to describe sets is a listing of its elements. In this case, the elements of the set are written in curly brackets separated by commas. For example, let's give the set A = (1, 2,3, 4), from the above notation we can say that it consists of three elements, which are the numbers 1, 2,3 and 4.

Brackets and vector coordinates

When vectors begin to be considered in a certain coordinate system, the concept arises. One way to denote them involves listing the vector coordinates one by one in parentheses.

In textbooks for school students you can find two options for notating the coordinates of vectors; they differ in that one uses curly brackets, and the other uses round brackets. Here are examples of notation for vectors on the plane: or , these notations mean that vector a has coordinates 0, −3. In three-dimensional space, vectors have three coordinates, which are indicated in brackets next to the name of the vector, for example,  or

or  .

.

In higher educational institutions Another designation for vector coordinates is more common: an arrow or dash is often not placed above the name of the vector, an equal sign appears after the name, after which the coordinates are written in parentheses, separated by commas. For example, the notation a=(2, 4, −2, 6, 1/2) is a designation for a vector in five-dimensional space. And sometimes the coordinates of a vector are written in brackets and in a column; for example, let’s give a vector in two-dimensional space.

Brackets to indicate matrix elements

Parentheses have also found their use when listing elements matrices. The elements of matrices are most often written inside paired parentheses. For clarity, here is an example:  . However, sometimes square brackets are used instead of parentheses. The newly written matrix A in this notation will take the following form:

. However, sometimes square brackets are used instead of parentheses. The newly written matrix A in this notation will take the following form:  .

.

References.

- Mathematics. 6th grade: educational. for general education institutions / [N. Ya. Vilenkin and others]. - 22nd ed., rev. - M.: Mnemosyne, 2008. - 288 p.: ill. ISBN 978-5-346-00897-2.

- Algebra: textbook for 7th grade general education institutions / [Yu. N. Makarychev, N. G. Mindyuk, K. I. Neshkov, S. B. Suvorova]; edited by S. A. Telyakovsky. - 17th ed. - M.: Education, 2008. - 240 p. : ill. - ISBN 978-5-09-019315-3.

- Algebra: textbook for 8th grade. general education institutions / [Yu. N. Makarychev, N. G. Mindyuk, K. I. Neshkov, S. B. Suvorova]; edited by S. A. Telyakovsky. - 16th ed. - M.: Education, 2008. - 271 p. : ill. - ISBN 978-5-09-019243-9.

- Gusev V. A., Mordkovich A. G. Mathematics (a manual for those entering technical schools): Proc. allowance.- M.; Higher school, 1984.-351 p., ill.

- Pogorelov A.V. Geometry: Textbook. for 7-11 grades. avg. school - 2nd ed. - M.: Education, 1991. - 384 pp.: ill. - ISBN 5-09-003385-4.

- Geometry, 7-9: textbook for general education institutions / [L. S. Atanasyan, V. F. Butuzov, S. B. Kadomtsev, etc.]. – 18th ed. – M.: Education, 2008.- 384 p.: ill.- ISBN 978-5-09-019109-8.

- Rudenko V. N., Bakhurin G. A. Geometry: Prob. textbook for grades 7-9. avg. school / Ed. A. Ya. Tsukarya. - M.: Education, 1992. - 384 pp.: ill. - ISBN 5-09-004214-4.

In the previous lesson we dealt with factorization. We mastered two methods: putting the common factor out of brackets and grouping. In this lesson - the following powerful method: abbreviated multiplication formulas. In short - FSU.

Abbreviated multiplication formulas (square of sum and difference, cube of sum and difference, difference of squares, sum and difference of cubes) are extremely necessary in all branches of mathematics. They are used in simplifying expressions, solving equations, multiplying polynomials, reducing fractions, solving integrals, etc. etc. In short, there is every reason to deal with them. Understand where they come from, why they are needed, how to remember them and how to apply them.

Do we understand?)

Where do abbreviated multiplication formulas come from?

Equalities 6 and 7 are not written in a very familiar way. It's kind of the opposite. This is on purpose.) Any equality works both from left to right and from right to left. This entry makes it clearer where the FSUs come from.

They are taken from multiplication.) For example:

(a+b) 2 =(a+b)(a+b)=a 2 +ab+ba+b 2 =a 2 +2ab+b 2

That's it, no scientific tricks. We simply multiply the brackets and give similar ones. This is how it turns out all abbreviated multiplication formulas. Abbreviated multiplication is because in the formulas themselves there is no multiplication of brackets and reduction of similar ones. Abbreviated.) The result is immediately given.

FSU needs to be known by heart. Without the first three, you can’t dream of a C; without the rest, you can’t dream of a B or A.)

Why do we need abbreviated multiplication formulas?

There are two reasons to learn, even memorize, these formulas. The first is that a ready-made answer automatically reduces the number of errors. But this is not the main reason. But the second one...

If you like this site...

By the way, I have a couple more interesting sites for you.)

You can practice solving examples and find out your level. Testing with instant verification. Let's learn - with interest!)

You can get acquainted with functions and derivatives.

Ushakov's Dictionary

Bracket

bracket, brackets, wives

1. Small staple; decrease to 1, 2 and 3 meaning “First a nail, then another, then a bracket.” Krylov.

2. A punctuation mark is a vertical line, usually semicircular, that is placed in front and behind various explanatory words (introductory and otherwise). Open parentheses (Place a parenthesis before a word). Close parentheses (Put a parenthesis after a word). Put, write the word in brackets. Place in parentheses.

| Mathematical sign - plumb line, semicircular ( so-called"round" bracket), or straight (with ends bent at right angles, "square"), or curved ("curly"), which is placed in front and behind the algebraic expression and indicates that the action is performed on this entire expression. Expand brackets (perform the specified action on the expression enclosed in brackets). Place outside the brackets or outside the brackets (the common factor included in each of the terms of the algebraic expression is written once outside the brackets).

3. A method of cutting hair in which it is cut in a straight line on the forehead and back of the head. Haircut in brackets ( cm. ). “The black curls lie in a bracket.” A.Koltsov. The kid was tall, fresh, healthy, *****

Dictionary of gold mining of the Russian Empire

Bracket

and. A metal strip bent at an angle, driven inside the barrel and used to break viscous rocks. To speed up the operation, iron brackets are stuffed into the barrels, against which the pebbles rub and the clay breaks. GZh, 1846, No. 6: 345.

Phraseological Dictionary of the Russian Language

Bracket

Say(or notice, note etc.) in brackets what - to mention something by the way, incidentally, by the way

Phraseological Dictionary (Volkova)

Bracket

In parentheses(be said, speaking, etc.) - trans. by the way, by the way.

I only note in parentheses that there is no despicable slander,... which your friend with a smile... would not repeat a mistake a hundred times. A. Pushkin.

In parentheses, we note that he guessed completely. Dostoevsky.

Ozhegov's Dictionary

SK ABOUT BKA 1, And, and. A written or printed sign, usually in pairs, that serves to distinguish a type. parts of the text, and in mathematics to indicate the order of performing mathematical operations. Parentheses (semicircular). Square brackets (). Curly braces (( )). Broken brackets (). Put the word in brackets. Put in brackets, put out of brackets. Open the brackets. Say, notice in parentheses(translated: mention in passing, by the way).

| decrease parenthesis, And, and.

| adj. bracket, oh, oh.

SK ABOUT BKA 2, And, and. A method of cutting hair in which it is cut evenly around the entire head and forehead. Get your hair cut into braces.

Parentheses

§ 188. Brackets contain words and sentences inserted into a sentence for the purpose of explaining or supplementing the thought expressed, as well as for any additional comments (for dashes with such insertions, see §). The following may be included in a sentence:

1. Words or sentences that are not syntactically related to a given sentence and are given to explain the entire thought as a whole or part of it, for example:

- Halfway through the stretch the forest ended and elani (fields) opened up on the sides...

L. Tolstoy

Ovsyanikov adhered to ancient customs not out of superstition (his soul was quite free), but out of habit.

Turgenev

2. Words and sentences that are not syntactically related to this sentence and are given as an additional comment, including those expressing questions or exclamation, for example:

- Believe me (conscience is our guarantee), marriage will be torment for us.

Pushkin

Having reconciled my inexperienced soul with time (who knows?), I would have found a friend after my heart.

Pushkin

Our poets are masters themselves, and if our patrons (damn them!) don’t know this, then so much the worse for them.

Pushkin

3. Words and sentences, although syntactically related to a given sentence, are given as an additional, secondary note, for example:

- Sad (as they say, mechanically) Tatyana silently leaned, bowing her head languidly.

Pushkin

But the goal of the eyes and judgments at that time was the fatty pie (unfortunately, over-salted).

Pushkin

It remains for us to summarize the individual features scattered in this article (for the incompleteness and awkwardness of which we apologize to the readers) and draw a general conclusion.

Dobrolyubov

§ 189. Phrases indicating the attitude of listeners to the speech of a person being presented are placed in brackets, for example:

- (Applause.)

(Laughter.)

(Movement in the hall.)

§ 190. Directly following the quotation, parentheses indicate the name of the author and the title of the work from which the quotation is taken.

§ 191. Stage directions in a dramatic text are placed in brackets.