Two striking events in the reign of Alexander 3. Alexander III - a short biography. Enthronement

Russia has only one possible ally. This is its army and navy.

Alexander 3

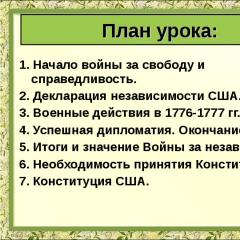

Thanks to his foreign policy, Alexander 3 received the nickname “Tsar-Peacemaker.” He sought to maintain peace with all his neighbors. However, this does not mean that the emperor himself did not have more distant and specific goals. He considered the main “allies” of his empire to be the army and navy, to which he paid a lot of attention. In addition, the fact that the emperor personally followed foreign policy indicates the priority of this direction for Alexander 3. The article examines the main directions of the foreign policy of Alexander 3, and also analyzes where he continued the line of previous emperors and where he introduced innovations.

Main tasks of foreign policy

The foreign policy of Alexander 3 had the following main objectives:

- Avoidance of war in the Balkans. The absurd and treacherous actions of Bulgaria literally dragged Russia into a new war that was not beneficial for it. The price of maintaining neutrality was the loss of control over the Balkans.

- Maintaining peace in Europe. Thanks to the position of Alexander 3, several wars were avoided at once.

- Solving problems with England regarding the division of spheres of influence in Central Asia. As a result, a border was established between Russia and Afghanistan.

Main directions of Foreign Policy

Alexander 3 and the Balkans

After the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878, the Russian Empire finally established itself as the protector of the South Slavic peoples. The main result of the war was the formation of the independent state of Bulgaria. The key factor in this event was the Russian army, which not only instructed the Bulgarian, but also fought for the independence of Bulgaria. As a result, Russia hoped to receive a reliable ally with access to the sea in the person of the then ruler Alexander Battenberg. Moreover, the role of Austria-Hungary and Germany is increasingly increasing in the Balkans. The Habsburg Empire annexed Bosnia and also increased its influence over Serbia and Romania. After Russia helped the Bulgarians create their own state, a constitution was developed specifically for them. However, in 1881, Alexander Battenberg led a coup d'état and abolished the newly adopted constitution, establishing virtual one-man rule.

This situation could threaten the rapprochement of Bulgaria with Austria-Hungary, or the beginning of a new conflict with the Ottoman Empire. In 1885, Bulgaria completely attacked Serbia, which further destabilized the situation in the region. As a result, Bulgaria annexed Eastern Rumelia, thereby violating the terms of the Berlin Congress. This threatened to start a war with the Ottoman Empire. And here the peculiarities of Alexander III’s foreign policy emerged. I understand the senselessness of a war for the interests of ungrateful Bulgaria; the emperor recalled all Russian officers from the country. This was done in order not to drag Russia into a new conflict, especially one that broke out due to the fault of Bulgaria. In 1886, Bulgaria broke off diplomatic relations with Russia. Independent Bulgaria, created in fact through the efforts of the Russian army and diplomacy, began to show excessive tendencies towards unifying part of the Balkans, violating international treaties (including with Russia), causing serious destabilization in the region.

Finding new allies in Europe

Until 1881, the “Union of Three Emperors” was actually in effect, signed between Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary. It did not provide for joint military action; in fact, it was a non-aggression pact. However, in the event of a European conflict, it could become the basis for the formation of a military alliance. It was at this point that Germany entered into another secret alliance with Austria-Hungary against Russia. In addition, Italy was drawn into the alliance, the final decision of which was influenced by contradictions with France. This was the actual consolidation of a new European military bloc - the Triple Alliance.

In this situation, Alexander 3 was forced to start looking for new allies. The final point in the severance of relations with Germany (despite the family ties of the emperors of the two countries) was the “customs” conflict of 1877, when Germany significantly increased the duty on Russian goods. At this moment there was a rapprochement with France. The agreement between the countries was signed in 1891 and became the basis for the formation of the Entente bloc. Rapprochement with France at this stage was able to prevent the Franco-German war, as well as the brewing conflict between Russia and Austria-Hungary.

Asian politics

During the reign of Alexander 3 in Asia, Russia had two areas of interest: Afghanistan and the Far East. In 1881, the Russian army annexed Ashgabat, and the Trans-Caspian region was formed. This caused a conflict with England, since it was not satisfied with the approach of the Russian army to its territories. The situation threatened war; there was even talk of attempts to create an anti-Russian coalition in Europe. However, in 1885, Alexander 3 moved towards rapprochement with England and the parties signed an agreement on the creation of a commission that was supposed to establish the border. In 1895, the border was finally drawn, thereby reducing tension in relations with England.

In the 1890s, Japan began to rapidly gain strength, which could have disrupted Russia's interests in the Far East. That is why in 1891 Alexander 3 signed a decree on the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

In what areas of foreign policy did Alexander 3 adhere to traditional approaches?

As for the traditional approaches to the foreign policy of Alexander 3, they consisted of the desire to preserve Russia’s role in the Far East and Europe. To achieve this, the emperor was ready to enter into alliances with European countries. In addition, like many Russian emperors, Alexander 3 devoted great influence to strengthening the army and navy, which he considered “Russia’s main allies.”

What were the new features of Alexander 3’s foreign policy?

Analyzing the foreign policy of Alexander 3, one can find a number of features that were not inherent in the reign of previous emperors:

- The desire to act as a stabilizer of relations in the Balkans. Under any other emperor, the conflict in the Balkans would not have passed without Russia's participation. In a situation of conflict with Bulgaria, a scenario of a forceful solution to the problem was possible, which could lead to a war either with Turkey or with Austria-Hungary. Alexander understood the role of stability in international relations. That is why Alexander 3 did not send troops into Bulgaria. In addition, Alexander understood the role of the Balkans for stability in Europe. His conclusions turned out to be correct, because it was this territory that at the beginning of the twentieth century finally became the “powder keg” of Europe, and it was in this region that the countries began the First World War.

- The role of “conciliatory force”. Russia acted as a stabilizer of relations in Europe, thereby preventing a war with Austria, as well as a war between France and Germany.

- Alliance with France and reconciliation with England. In the mid-nineteenth century, many were confident in the future union with Germany, as well as in the strength of this relationship. However, in the 1890s, alliances began to be formed with France and England.

And another small innovation, compared to Alexander 2, was personal control over foreign policy. Alexander 3 removed the previous Minister of Foreign Affairs A. Gorchakov, who actually determined foreign policy under Alexander 2, and appointed an obedient executor N. Girs.

If we sum up the 13-year reign of Alexander 3, then we can say that in foreign policy he took a wait-and-see attitude. For him there were no “friends” in international relations, but, first of all, the interests of Russia. However, the emperor sought to achieve them through peace agreements.

The name of Emperor Alexander III, one of the greatest statesmen of Russia, was consigned to desecration and oblivion for many years. And only in recent decades, when the opportunity arose to speak unbiasedly and freely about the past, evaluate the present and think about the future, the public service of Emperor Alexander III arouses great interest of all who are interested in the history of their country.

Emperor Alexander III was not destined to reign by birth. Being the second son of Alexander II, he became the heir to the Russian throne only after the premature death of his older brother Tsarevich Nikolai Alexandrovich in 1865. At the same time, on April 12, 1865, the Highest Manifesto announced to Russia the proclamation of Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich as the heir-Tsarevich, and a year later the Tsarevich married the Danish princess Dagmara, who was named Maria Feodorovna in marriage.

On the anniversary of his brother’s death on April 12, 1866, he wrote in his diary: “I will never forget this day... the first funeral service over the body of a dear friend... I thought in those minutes that I would not survive my brother, that I would constantly cry at just one thought that I no longer have a brother and friend. But God strengthened me and gave me strength to take on my new assignment. Perhaps I often forgot my purpose in the eyes of others, but in my soul there was always this feeling that I should not live for myself, but for others; heavy and difficult duty. But: “Thy will be done, O God”. I repeat these words constantly, and they always console and support me, because everything that happens to us is all the will of God, and therefore I am calm and trust in the Lord!” The awareness of the gravity of obligations and responsibility for the future of the state, entrusted to him from above, did not leave the new emperor throughout his short life.

The educators of Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich were Adjutant General, Count V.A. Perovsky, a man of strict moral rules, appointed by his grandfather Emperor Nicholas I. The education of the future emperor was supervised by the famous economist, professor at Moscow University A.I. Chivilev. Academician Y.K. Grot taught Alexander history, geography, Russian and German; prominent military theorist M.I. Dragomirov - tactics and military history, S.M. Soloviev - Russian history. The future emperor studied political and legal sciences, as well as Russian legislation, from K.P. Pobedonostsev, who had a particularly great influence on Alexander. After graduation, Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich traveled throughout Russia several times. It was these trips that laid in him not only love and the foundations of deep interest in the fate of the Motherland, but also formed an understanding of the problems facing Russia.

As heir to the throne, the Tsarevich participated in meetings of the State Council and the Committee of Ministers, was the chancellor of the University of Helsingfors, ataman of the Cossack troops, and commander of the guards units in St. Petersburg. In 1868, when Russia suffered a severe famine, he became the head of a commission formed to provide assistance to the victims. During the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878. he commanded the Rushchuk detachment, which played an important and difficult role tactically: it held back the Turks from the east, facilitating the actions of the Russian army, which was besieging Plevna. Realizing the need to strengthen the Russian fleet, the Tsarevich made an ardent appeal to the people for donations to the Russian fleet. In a short time the money was collected. The Volunteer Fleet ships were built on them. It was then that the heir to the throne became convinced that Russia had only two friends: its army and navy.

He was interested in music, fine arts and history, was one of the initiators of the creation of the Russian Historical Society and its chairman, and was involved in collecting collections of antiquities and restoring historical monuments.

|

The government, formed with the participation of the Chief Prosecutor of the Holy Synod K.P. Pobedonostsev, concentrated his attention on strengthening the “traditionalist” principles in politics, economics and culture of the Russian Empire. In the 80s - mid 90s. a series of legislative acts appeared that limited the nature and actions of those reforms of the 60-70s, which, according to the emperor, did not correspond to the historical purpose of Russia. Trying to prevent the destructive force of the opposition movement, the emperor introduced restrictions on zemstvo and city self-government. The elective principle in the magistrate court was reduced, and in the counties the execution of judicial duties was transferred to the newly established zemstvo chiefs.

At the same time, steps were taken aimed at developing the state's economy, strengthening finances and carrying out military reforms, and resolving agrarian-peasant and national-religious issues. The young emperor also paid attention to the development of the material well-being of his subjects: he founded the Ministry of Agriculture to improve agriculture, established noble and peasant land banks, with the assistance of which nobles and peasants could acquire land property, patronized domestic industry (by increasing customs duties on foreign goods ), and by constructing new canals and railways, including through Belarus, contributed to the revival of the economy and trade.

|

State policy in Belarus was dictated, first of all, by the reluctance to “forcibly break the historically established system of life” of the local population, the “forceful eradication of languages” and the desire to ensure that “foreigners become modern sons, and not remain eternal adopted children of the country.” It was at this time that general imperial legislation, administrative and political management and the education system were finally established on the Belarusian lands. At the same time, the authority of the Orthodox Church rose.

In foreign policy affairs, Alexander III tried to avoid military conflicts, which is why he went down in history as the “Tsar-Peacemaker.” The main direction of the new political course was to ensure Russian interests by finding support for “ourselves.” Having become closer to France, with which Russia had no controversial interests, he concluded a peace treaty with her, thereby establishing an important balance between European states. Another extremely important policy direction for Russia was maintaining stability in Central Asia, which shortly before the reign of Alexander III became part of the Russian Empire. The borders of the Russian Empire then advanced to Afghanistan. In this vast space, a railway was laid connecting the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea with the center of Russian Central Asian possessions - Samarkand and the river. Amu Darya. In general, Alexander III persistently strove for complete unification of all border regions with indigenous Russia. To this end, he abolished the Caucasian governorship, destroyed the privileges of the Baltic Germans and prohibited foreigners, including Poles, from acquiring land in Western Russia, including Belarus.

The emperor also worked hard to improve military affairs: the Russian army was significantly enlarged and armed with new weapons; Several fortresses were built on the western border. The navy under him became one of the strongest in Europe.

|

An extremely important matter of the era of Alexander III were parochial schools. The Emperor saw the parish school as one of the forms of cooperation between the State and the Church. The Orthodox Church, in his opinion, has been the educator and teacher of the people from time immemorial. For centuries, schools at churches were the first and only schools in Rus', including Belaya. Until the mid-60s. In the 19th century, almost exclusively priests and other members of the clergy were tutors in rural schools. On June 13, 1884, the Emperor approved the “Rules on Parish Schools.” Approving them, the emperor wrote in a report about them: “I hope that the parish clergy will be worthy of their high calling in this important matter.” Church and parochial schools began to open in many places in Russia, often in the most remote and remote villages. Often they were the only source of education for the people. At the accession of Emperor Alexander III to the throne, there were only about 4,000 parochial schools in the Russian Empire. In the year of his death there were 31,000 of them and they educated more than a million boys and girls.

Along with the number of schools, their position also strengthened. Initially, these schools were based on church funds, on funds from church fraternities and trustees and individual benefactors. Later, the state treasury came to their aid. To manage all parochial schools, a special school council was formed under the Holy Synod, publishing textbooks and literature necessary for education. While taking care of the parochial school, the emperor realized the importance of combining the fundamentals of education and upbringing in a public school. The emperor saw this education, which protects the people from the harmful influences of the West, in Orthodoxy. Therefore, Alexander III was especially attentive to the parish clergy. Before him, the parish clergy of only a few dioceses received support from the treasury. Under Alexander III, the release of funds from the treasury to provide for the clergy began. This order marked the beginning of improving the life of the Russian parish priest. When the clergy expressed gratitude for this undertaking, he said: “I will be quite happy when I manage to provide for all the rural clergy.”

Emperor Alexander III treated the development of higher and secondary education in Russia with the same care. During his short reign, Tomsk University and a number of industrial schools were opened.

The tsar's family life was impeccable. From his diary, which he kept daily when he was his heir, one can study the daily life of an Orthodox person no worse than from the famous book by Ivan Shmelev “The Summer of the Lord.” Alexander III received true pleasure from church hymns and sacred music, which he valued much higher than secular music.

Emperor Alexander reigned for thirteen years and seven months. Constant worries and intensive studies early on broke his strong nature: he began to feel increasingly unwell. Before the death of Alexander III, St. confessed and received communion. John of Kronstadt. Not for a minute did the king’s consciousness leave him; Having said goodbye to his family, he said to his wife: “I feel the end. Be calm. “I am completely calm”... “About half past 3 he took communion,” the new Emperor Nicholas II wrote in his diary on the evening of October 20, 1894, “slight convulsions soon began, ... and the end quickly came!” Father John stood at the head of the bed for more than an hour and held his head. It was the death of a saint!” Alexander III died in his Livadia Palace (in Crimea) before reaching his fiftieth birthday.

The personality of the emperor and his significance for the history of Russia are rightly expressed in the following verses:

In the hour of turmoil and struggle, having ascended under the shadow of the throne,

He extended his powerful hand.

And the noisy sedition around them froze.

Like a dying fire.

He understood the spirit of Rus' and believed in its strength,

Loved its space and breadth,

He lived like a Russian Tsar, and he went to his grave,

Like a true Russian hero.

The initial period of the reign of Alexander III. After the death of Alexander II, his second son Alexander III (1881-1894) ascended the throne. A man of rather ordinary abilities and conservative views, he did not approve of many of his father’s reforms and did not see the need for serious changes (primarily in solving the key issue - providing peasants with land, which could significantly strengthen the social support of the autocracy). At the same time, Alexander III was not devoid of natural common sense and, unlike his father, had a stronger will.

Soon after the assassination of Alexander II, which sowed panic in high circles, the leaders of Narodnaya Volya were arrested. April 3, 1881 involved in the assassination attempt on the late Emperor SL. Perovskaya, A.I. Zhelyabov, N.I. Kibalchich, N.I. Rysakov and T.M. Mikhailov were hanged, and G.M. Gelfman soon died in prison.

On March 8 and 21, meetings of the Council of Ministers were held at which the Loris-Melikov project was discussed. Chief Prosecutor of the Holy Synod, former educator of Alexander III and prominent conservative K. P. Pobedonostsev sharply opposed the project, considering it a prototype of the constitution. And although the guardians of the project made up the majority, Alexander III postponed its consideration, after which they did not return to it.

April 29, 1881 A royal manifesto written by Pobedonostsev was published. It spoke of protecting the autocracy from any “encroachments,” that is, from constitutional changes. Having seen hints in the manifesto of abandoning reforms altogether, the liberal ministers resigned - D.A. Milyutin, M.T. Loris-Melikov, A.A. Abaza (Minister of Finance). Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich was removed from the leadership of the fleet.

The director of the Police Department, which replaced the III Division, became V.K. Pleve, and in 1884 - I.P. Durnovo. The political search was directly led by Lieutenant Colonel G.P. Sudeikin, who, largely with the help of converted revolutionaries, primarily S.P. .Degaev, almost completely defeated “People's Will”. True, in December 1883 he himself was killed by Degaev. who considered his cooperation with the police unprofitable, but this, of course, could not save the revolutionary movement.

In parallel with the police in March, the “Holy Squad”, which emerged in March 1881, fought against the revolutionaries, which included more than 700 officials, generals, bankers, including P. A. Shuvalov, S. Yu. Witte, B. V. Sturmer S. With the help of its own agents, this voluntary organization tried to undermine the revolutionary movement. But already at the end of 1881, Alexander III ordered the dissolution of the “Holy Squad,” the existence of which indirectly indicated the inability of the authorities to independently cope with “sedition.”

In August 1881, according to the “Regulations on measures to protect state order and public peace,” the Minister of Internal Affairs and provincial authorities received the right to arrest, expel and bring to trial suspicious persons, close educational institutions and enterprises, ban the publication of newspapers, etc. . Any locality could be declared in fact a state of emergency. Introduced for 3 years, the “Regulation” was extended several times and was in force until 1917.

But the authorities did not limit themselves to repression alone, trying to carry out certain positive changes. The first government of Alexander III included several liberal ministers, primarily the Minister of Internal Affairs N. P. Ignatiev and Finance N. X. Bunge. Their activities are associated with such measures as the abolition in 1881 of the temporary obligation of peasants, the reduction of redemption payments, and the gradual abolition of the heavy poll tax. In November 1881, a commission headed by Loris-Melikov’s former deputy, M. S. Kakhanov, began work on a local government reform project. However, in 1885 the commission was dissolved, and its activities had no real results.

In April 1882, Ignatiev proposed to Alexander III to convene a Zemsky Sobor in May 1883, which was supposed to confirm the inviolability of the autocracy. This caused sharp criticism from Pobedonostsev, and the tsar, who did not want any elected representation, was also dissatisfied. Moreover, autocracy, in his opinion, needed no confirmation. As a result, in May 1882, N.P. Ignatiev was replaced as Minister of Internal Affairs by the conservative D.A. Tolstoy.

The period of counter-reforms. Ignatiev's resignation and his replacement by Tolstoy marked a departure from the policy of moderate reforms carried out in 1881-1882 and a transition to the offensive against the transformations of the previous reign. True, it was only about “correcting” the “extremes” committed under Alexander II, which were, in the opinion of the Tsar and his entourage, “alien” in the Russian environment. The corresponding measures were called counter-reforms.

In May 1883, during the coronation celebrations, Alexander III made a speech to representatives of peasant self-government - volost elders, in which he called on them to follow the “advice and leadership of their leaders of the nobility” and not rely on “free additions” to the peasants’ plots. This meant that the government intended to continue to rely on the “noble” class, which had no historical perspective, and did not want to solve the country’s most important problem - land.

The first major counter-reform was the university statute of 1884, which sharply limited the autonomy of universities and increased tuition fees.

In July 1889, the zemstvo counter-reform began. Contrary to the opinion of the majority of members of the State Council, the position of zemstvo chiefs was introduced, designed to replace peace mediators and justices of the peace. They were appointed by the Minister of Internal Affairs from among the hereditary nobles and could approve and remove representatives of peasant self-government, impose punishments, including corporal, resolve land disputes, etc. All this created great opportunities for arbitrariness, strengthened the power of the nobles over the peasants and in no way did not improve the work of zemstvo bodies.

In June 1890, the “Regulations on provincial and district zemstvo institutions” were adopted. It introduced the class principle of elections to zemstvos. The first curia was noble, the second - urban, the third - peasant. For nobles, the property qualification was lowered, and for representatives of cities it was increased. As for the representatives from the peasants, they were appointed by the governor from among the candidates elected by the peasants. However, having again encountered the opposition of the majority of the State Council, Alexander III refrained from completely eliminating the election and all-class status of zemstvo bodies.

In 1892, a new city regulation was adopted, according to which the electoral qualification was increased, and the mayor and members of the city government became civil servants subordinate to the governors.

Counter-reforms in the field of justice lasted for several years. In 1887, the ministers of the interior and justice received the right to declare court sessions closed, and the property and educational qualifications for jurors increased. In 1889, cases of crimes against the order of government, malfeasance, etc. were removed from the jurisdiction of jury courts. However, the publicity of most courts, competitiveness, and the irremovability of judges remained in force, and the plans of the Minister of Justice appointed in 1894 in 1894 N V. Muravyov's complete revision of the judicial statutes of 1864 was prevented by the death of Alexander III.

Censorship policies have become stricter. According to the “Temporary Rules on the Press,” adopted in August 1882, the Ministries of Internal Affairs, Education and the Synod could close “seditious” newspapers and magazines. Publications that received a warning from the authorities were subject to preliminary censorship. Special circulars prohibited coverage in the press of such topics as the labor question, land redistribution, problems of educational institutions, the 25th anniversary of the abolition of serfdom, and the actions of the authorities. Under Alexander III, the liberal newspapers “Strana”, “Golos”, “Moscow Telegraph”, the magazine “Domestic Notes” edited by M. E. Saltykov-Shchedrin, a total of 15 publications, were closed. The non-periodical press was also persecuted, although not as harshly as newspapers and magazines. Total in 1881-1894. 72 books were banned - from the freethinker L.N. Tolstoy to the completely conservative N.S. Leskov. “Seditious” literature was confiscated from libraries: works by L.N. Tolstoy, N.A. Dobrolyubov, V.G. Korolenko, issues of the magazines “Sovremennik” for 1856-1866, “Notes of the Fatherland” for 1867-1884. More than 1,300 plays were banned.

A policy of Russification of the outskirts of the empire and infringement of local autonomy was actively pursued. In Finland, instead of the previous financial autonomy, mandatory acceptance of Russian coins was introduced, and the rights of the Finnish Senate were curtailed. In Poland, now called not the Kingdom of Poland, but the Privislensky region, compulsory teaching in Russian was introduced, and the Polish Bank was closed. The policy of Russification was actively pursued in Ukraine and Belarus, where virtually no literature was published in national languages, and the Uniate Church was persecuted. In the Baltics, local judicial and administrative bodies were actively replaced by imperial ones, the population converted to Orthodoxy, and the German language of the local elite was supplanted. The policy of Russification was also carried out in Transcaucasia; The Armenian Church was persecuted. Orthodoxy was forcibly introduced among Muslims and pagans of the Volga region and Siberia. In 1892-1896. The Multan case, fabricated by the authorities, was investigated, accusing Udmurt peasants of making human sacrifices to pagan gods (in the end, the defendants were acquitted).

The rights of the Jewish population, whose residence the government sought to limit to the so-called “Pale of Settlement,” were limited. Their residence in Moscow and the Moscow province was limited. Jews were prohibited from purchasing property in rural areas. In 1887, the Minister of Education I.P. Delyanov reduced the enrollment of Jews in higher and secondary educational institutions.

Social movement. After the assassination of Alexander II, liberals sent an address to the new tsar condemning the terrorists and expressing hope for the completion of reforms, which, however, did not happen. In conditions of intensified reaction, opposition sentiments are growing among ordinary zemstvo employees - doctors, teachers, statisticians. More than once zemstvo officials tried to act beyond the scope of their powers, which led to clashes with the administration.

The more moderate part of the liberals preferred to refrain from manifestations of opposition. The influence of liberal populists (N.K. Mikhailovsky, N.F. Danielson, V.P. Vorontsov) grew. They called for reforms that would improve the lives of the people, and above all for the abolition of landownership. At the same time, liberal populists did not approve of revolutionary methods of struggle and preferred cultural and educational work, acting through the press (the magazine “Russian Wealth”), zemstvos, and public organizations.

However, in general, government oppression (often quite senseless) stimulated discontent among the intelligentsia and contributed to its transition to radical positions.

The main ideologists of the reaction are the chief prosecutor of the Synod, K. P. Pobedonostsev, the editor-in-chief of Moskovskie Vedomosti and Russky Vestnik, M. N. Katkov, and the editor of the magazine Citizen, V. P. Meshchersky. They condemned liberal reforms, defended the narrowly understood identity of Russia and welcomed the counter-reforms of Alexander III. “Stand up, gentlemen,” Katkov wrote gloatingly about the counter-reforms. “The government is coming, the government is coming back.” Meshchersky was supported, including financially, by the par himself.

There is a crisis in the revolutionary movement associated with the defeat of Narodnaya Volya. True, scattered populist groups continued to operate after this. The circle of P.Ya. Shevyrev - A.I. Ulyanov (brother of V.I. Lenin) even prepared an assassination attempt on Alexander III on March 1, 1887, which ended with the arrest and execution of five conspirators. Many revolutionaries completely abandoned their previous methods of struggle, advocating an alliance with the liberals. Other revolutionaries, disillusioned with populism with its naive hopes for the peasantry, became increasingly imbued with the ideas of Marxism. In September 1883, former members of the “Black Redistribution” who lived in Switzerland - P. B. Axelrod, G. V. Plekhanov, V. I. Zasulich, L. G. Deich - created the social democratic group “Emancipation of Labor” , which began to publish Marxist literature in Russian and laid the theoretical foundations of Russian social democracy. Its most prominent figure was G. V. Plekhanov (1856-1918). In his works “Socialism and Political Struggle” and “Our Disagreements,” he criticized the populists and pointed out Russia’s unpreparedness for a socialist revolution. Plekhanov considered it necessary to form a social democratic party and carry out a bourgeois democratic revolution, which would create the economic prerequisites for the victory of socialism.

Since the mid-80s, Marxist circles have emerged in Russia itself in St. Petersburg, Odessa, Kiev, Kharkov, Kazan, Vilno, Tula, etc. Among them, the circles of D. N. Blagoev, N. E. Fedoseev, M. I. stood out. Brusnev, P.V. Tochissky. They read and distributed Marxist literature and carried out propaganda among the workers, but their significance was still small.

Work question. The situation of workers in Russia, the number of which had noticeably increased compared to the pre-reform period, was difficult: there was no labor protection, social insurance, or restrictions on the length of the working day, but an almost uncontrolled system of fines, low-paid female and child labor, mass layoffs, and reductions in wages were widespread. All this led to labor conflicts and strikes.

In the 80s, the government began to take measures to regulate relations between workers and employers. In 1882, the use of child labor was limited, and a factory inspectorate was created to oversee this. In 1884, a law introduced training for children who worked in factories.

An important milestone in the development of the strike movement and labor legislation was the strike at Morozov’s Nikolskaya manufactory in Orekhovo-Zuevo in January 1885. It was organized in advance, 8 thousand people took part in it, and it was led by P. A. Moiseenko and V. S. Volkov . The workers demanded that the manufacturer streamline the system of fines and dismissal rules, and that the government limit the arbitrariness of employers. More than 600 people were expelled to their native villages, 33 were put on trial but acquitted (Moiseenko and Volkov, however, were expelled after the trial administratively).

At the same time, the government satisfied some of the workers' demands. Already in June 1885, the exploitation of women and children at night was prohibited, a system of fines was streamlined, the income from which now went not to the employer, but to the needs of the workers themselves, and the procedure for hiring and firing workers was regulated. The powers of the factory inspection were expanded, and provincial presences were created for factory affairs.

A wave of strikes swept through enterprises in the Moscow and Vladimir provinces, St. Petersburg, and Donbass. These and other strikes forced factory owners in some cases to increase wages, shorten working hours, and improve workers' living conditions.

Foreign policy. During the reign of Alexander III, Russia did not wage wars, which earned the tsar the reputation of a “peacemaker.” This was due both to the opportunity to play on the contradictions between European powers and general international stability, and to the emperor’s dislike of wars. The executor of Alexander III's foreign policy plans was Foreign Minister N.K. Gire, who did not play an independent role like Gorchakov.

Having ascended the throne, Alexander III continued to establish ties with Germany, the most important trading partner and potential ally in the fight against England. In June 1881 Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary renewed the “Union of the Three Emperors” for 6 years. The parties promised to maintain neutrality in the event of war between one of them and the fourth power. At the same time, Germany entered into a secret agreement with Austria-Hungary directed against Russia and France. In May 1882, Italy joined the alliance of Germany and Austria-Hungary, which was promised assistance in the event of a war with France. This is how the Triple Alliance emerged in the center of Europe.

The “Union of the Three Emperors” brought certain benefits to Russia in its rivalry with England. In 1884, Russian troops completed the conquest of Turkmenistan and approached the borders of Afghanistan, which was under the protectorate of England; from here it was a stone's throw to the main British colony - India. In March 1885, a clash occurred between a Russian detachment and Afghan troops led by British officers. The Russians won. England, seeing this as a threat to its Indian possessions, threatened Russia with war, but was unable to put together an anti-Russian coalition in Europe. Support for Russia from Germany and Austria-Hungary, who did not want England to become too strong, played a role in this. Their position helped Alexander III get Turkey to close the Black Sea straits to the British fleet, which protected southern Russia from it. England had to recognize Russian conquests in Central Asia. Already in 1885, the drawing of the Russian-Afghan border by Russian-British commissions began.

Under Alexander III, Russia's position in the Balkans weakened. In 1881, a pro-German group came to power in Bulgaria. In 1883, Bulgaria entered into an agreement with Austria-Hungary. In 1885, Alexander III opposed the annexation of Eastern Rumelia to Bulgaria (in violation of the decisions of the Berlin Congress), although he threatened Turkey that he would not tolerate its invasion of Rumelia. In 1886, after the pro-Austrian regime came to power in Bulgaria, Russia tore relations with her In this conflict, Germany and Austria-Hungary did not support Russia, because they themselves wanted to strengthen their position in the Balkans. After 1887, the “Union of Three Emperors” was not renewed.

In the context of worsening relations with France, Bismarck signed a “reinsurance agreement” with Russia for 3 years in 1887. It provided for the neutrality of Russia in the event of an attack by France on Germany and the neutrality of Germany in the event of an attack on Russia by Austria-Hungary. Then, in 1887, Alexander III managed to keep Germany from attacking France, the defeat of which would have unnecessarily strengthened Germany. This led to a worsening of Russian-German relations and an increase in import duties on each other's goods by both countries. In 1893, a real customs war began between the two countries.

In conditions of hostility with England, Germany and Austria-Hungary, Russia needed an ally. They became France, which was constantly threatened by German aggression. Back in 1887, France began to provide large loans to Russia, which helped stabilize Russian finances. French investments in the Russian economy were also significant.

In August 1891, Russia and France signed a secret agreement on joint action in the event of an attack on one of them. In 1892, a draft military convention was developed, which provided for the number of troops on both sides in the event of war. The Russian-French alliance was finally formalized in January 1894. It seriously changed the balance of power in Europe, splitting it into two military-political groupings.

Socio-economic development. Under Alexander III, measures were taken to modernize the economy, on the one hand, and economic support for the nobility, on the other. Major successes in economic development were largely associated with the activities of the ministers of finance - N. X. Bunge, I. V. Vyshnegradsky, S. Yu. Witte.

Industry. By the 80s of the XIX century. The industrial revolution ended in Russia. The government patronized the development of industry with loans and high duties on imported products. True, in 1881 an industrial crisis began, associated with the economic consequences of the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878. and reduction in the purchasing power of the peasantry. In 1883 the crisis gave way to depression, in 1887 a revival began, and in 1893 a rapid growth of industry began. Mechanical engineering, metallurgy, coal and oil industries continued to develop successfully. Foreign investors increasingly invested their money in them. In terms of the rate of coal and oil production, Russia ranked 1st in the world. The latest technologies were actively introduced at enterprises. It should be noted that heavy industry provided less than 1/4 of the country's output, noticeably inferior to light industry, primarily textiles.

Agriculture. In this industry, the specialization of individual regions increased, the number of civilian workers increased, which indicated a transition to the bourgeois path of development. In general, grain farming continued to predominate. Productivity increased slowly due to the low level of agricultural technology. The fall in world grain prices had a detrimental effect. In 1891 - 1892 A terrible famine broke out, killing more than 600 thousand. people Under these conditions, the shortage of land among peasants became an extremely acute problem; Alexander III did not want to hear about increasing peasant plots at the expense of landowners; True, in 1889 a law was passed that encouraged the resettlement of peasants to empty areas - the settlers received tax benefits, exemption from military service for 3 years and a small cash allowance, but permission for resettlement was given only by the Ministry of the Interior. In 1882, the Peasant Bank was created, which provided low-interest loans to peasants to purchase land. The government tried to strengthen the peasant community and at the same time reduce the negative features of communal land use: in 1893, the exit of peasants from the community was limited, but at the same time it was difficult to redistribute land, which reduced the interest of the most enterprising peasants in the careful use of their plots. It was prohibited to mortgage and sell communal lands. An attempt to regulate and thereby reduce the number of family divisions, made in 1886, failed: the peasants simply ignored the law. To support the landed estates, the Noble Bank was created in 1885, which, however, did not stop their ruin.

Transport. Intensive construction of railways continued (under Alexander III, more than 30 thousand km were built). The railway network near the western borders, which was of strategic importance, developed especially actively. The iron ore-rich region of Krivoy Rog was connected with the Donbass, the Urals - with the central regions, both capitals - with Ukraine, the Volga region, Siberia, etc. In 1891, construction began on the strategically important Trans-Siberian Railway, connecting Russia with the Far East. The government began to buy out private railways, up to 60% of which by the mid-90s ended up in the hands of the state. The number of steamships by 1895 exceeded 2,500, increasing more than 6 times compared to 1860.

Trade. The development of commerce was stimulated by the growth of the transport network. The number of shops, stores, and commodity exchanges has increased. By 1895, domestic trade turnover increased 3.5 times compared to 1873 and reached 8.2 billion rubles.

In foreign trade, exports in the early 90s exceeded imports by 150-200 million rubles, largely due to high import duties, especially on iron and coal. In the 80s, a customs war began with Germany, which limited the import of Russian agricultural products. In response, Russia raised duties on German goods. The first place in Russian exports was occupied by bread, followed by timber, wool, and industrial goods. Machines, raw cotton, metal, coal, tea, and oil were imported. Russia's main trading partners were Germany and England. Holland. USA.

Finance. In 1882-1886, the heavy capitation tax was abolished, which, thanks to the skillful policy of the Minister of Finance Bunge, was generally compensated by increasing indirect taxes and customs duties. In addition, the government refused to guarantee the profitability of private railways at the expense of the treasury.

In 1887, Bunge, who was accused of being unable to overcome the budget deficit, was replaced by I.V. Vyshnegradsky. He sought to increase cash savings and increase the exchange rate of the ruble. To this end, successful exchange operations were carried out, indirect taxes and import duties increased again, for which a protectionist customs tariff was adopted in 1891. In 1894, under S. Yu. Witte, a wine monopoly was introduced. As a result of these and other measures managed to overcome the budget deficit.

Education. Counter-reforms also affected the education sector. They were aimed at raising a trustworthy, obedient intelligentsia. In 1882, instead of the liberal A.N. Nikolai, the reactionary I.P. Delyanov became the Minister of Education. In 1884, parochial schools came under the jurisdiction of the Synod. Their number increased by 1894 almost 10 times; the level of teaching in them was low; the main task was considered to be education in the spirit of Orthodoxy. But still, parochial schools contributed to the spread of literacy.

The number of gymnasium students continued to grow (in the 90s - more than 150 thousand people). In 1887, Delyanov issued a “circular about cooks’ children,” which made it difficult to admit children of laundresses, cooks, footmen, coachmen, etc. to the gymnasium. Tuition fees have increased.

In August 1884 a new University Charter was adopted, which essentially abolished the autonomy of universities, which now fell under the control of the trustee of the educational district and the Minister of Education. The rector, deans and professors were now appointed, not so much taking into account scientific merit as political reliability. A fee was introduced for students to attend lectures and practical classes.

In 1885, the uniform for students was reintroduced; in 1886, the period of military service for persons with higher education was increased to 1 year. Since 1887, a certificate of political reliability was required for admission to universities. The government has significantly reduced spending on universities, making scientific research more difficult. Some free-thinking professors were fired, others left in protest. Under Alexander III, only one university was opened - in Tomsk (1888). In 1882, higher medical courses for women were closed, and in 1886, admission to all higher courses for women ceased, the elimination of which was sought by K. P. Pobedonostsev. True, the Bestuzhev courses in St. Petersburg nevertheless resumed work, albeit in a limited number.

Culture of Russia in the 2nd half of the 19th century. The science. This period was marked by new important discoveries in various branches of science. I.M. Sechenov created the doctrine of brain reflexes, laying the foundations of Russian physiology. Continuing research in this direction, I. P. Pavlov developed a theory of conditioned reflexes. I. I. Mechnikov made a number of important discoveries in the field of phagocytosis (the protective functions of the body), created a school of microbiology and comparative pathology, together with N. F. Gamaleya organized the first bacteriological station in Russia, and developed methods to combat rabies. K. A. Timiryazev did a lot to study photosynthesis and became the founder of domestic plant physiology. V.V. Dokuchaev gave rise to scientific soil science with his works “Russian Chernozem” and “Our Steppes Before and Now”.

Chemistry has achieved the greatest successes. A. M. Butlerov laid the foundations of organic chemistry. D.I. Mendeleev in 1869 discovered one of the basic laws of natural science - the periodic law of chemical elements. He also made a number of discoveries not only in chemistry, but also in physics, metrology, hydrodynamics, etc.

The most prominent mathematician and mechanic of his time was P. L. Chebyshev, who was engaged in research in the field of number theory, probability, machines, and mathematical analysis. In an effort to put the results of his research into practice, he also invented a plantigrade machine and an adding machine. S. V. Kovalevskaya, author of works on mathematical analysis, mechanics and astronomy, became the first woman professor and corresponding member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. A. M. Lyapunov gained worldwide fame for his research in the field of differential equations.

Russian physicists made a significant contribution to the development of science. A.G. Stoletov conducted a number of important studies in the field of electricity, magnetism, gas discharge, and discovered the first law of the photoelectric effect. In 1872, A. N. Lodygin invented a carbon incandescent lamp, and P. Ya. Yablochkov in 1876 patented an arc lamp without a regulator (Yablochkov candle), which from 1876 began to be used for street lighting.

In 1881, A.F. Mozhaisky designed the world's first aircraft, the tests of which, however, were unsuccessful. In 1888, self-taught mechanic F.A. Blinov invented a caterpillar tractor. In 1895, A.S. Popov demonstrated the world's first radio receiver, which he had invented, and soon achieved a transmission and reception range of 150 km. The founder of astronautics, K. E. Tsiolkovsky, began his research, having designed a simple wind tunnel and developed the principles of the theory of rocket propulsion.

2nd half of the 19th century was marked by new discoveries of Russian travelers - N. M. Przhevalsky, V. I. Roborovsky, N. A. Severtsov, A. P. and O. A. Fedchenko in Central Asia, P. P. Semenov-Tian-Shan- Sky in the Tien Shan, Ya. Ya. Miklouho-Maclay in New Guinea. The result of the expeditions of the founder of Russian climatology A.I. Voeikov across Europe, America and India was the major work “Climates of the Globe”.

Philosophical thought. During this period, philosophical thought flourished. The ideas of positivism (G.N. Vyrubov, M.M. Troitsky), Marxism (G.V. Plekhanov), religious philosophy (V.S. Solovyov, N.F. Fedorov), later Slavophilism (N.Ya. Danilevsky, K.N. Leontiev). N.F. Fedorov put forward the concept of mastering the forces of nature, overcoming death and resurrection with the help of science. The founder of the “philosophy of unity” V.S. Solovyov nurtured the idea of merging Orthodoxy and Catholicism and developed the doctrine of Sophia - the comprehensive divine wisdom that rules the world. N. Ya. Danshkevsky put forward a theory of cultural-historical types that develop similarly to biological ones; He considered the Slavic type to be gaining strength and therefore the most promising. K. Ya. Leontyev saw the main danger in Western-style liberalism, which, in his opinion, leads to the homogenization of individuals, and believed that only autocracy can prevent this homogenization.

Historical science is reaching a new level. In 1851-. 1879 29 volumes of “History of Russia from Ancient Times” by the outstanding Russian historian S. M. Solovyov were published, which outlined the history of Russia until 1775. Although the author was not yet aware of many sources, and a number of the positions he put forward were not confirmed, his work still retains its scientific significance. Solovyov’s pen also includes studies on the partitions of Poland, on Alexander I, inter-princely relations, etc. Solovyov’s student was V. O. Klyuchevsky, the author of the works “The Boyar Duma of Ancient Rus'”, “The Origin of Serfdom in Russia”, “The Lives of Old Russian Saints as a Historical source”, etc. His main work was “Course of Russian History”. An important contribution to the study of the history of the Russian community, church, and zemstvo councils was made by A.P. Shchapov. Research into the era of Peter I and the history of Russian culture brought fame to P. Ya. Milyukov. The history of Western Europe was studied by such prominent scientists as V. I. Gerye, M. M. Kovalevsky, P. G. Vinogradov, N. I. Kareev. Prominent scholars of antiquity were M. S. Kutorga, F. F. Sokolov, F. G. Mishchenko. Research on the history of Byzantium was carried out by V. G. Vasilievsky, F. I. Uspensky, Yu. A. Kulakovsky.

Literature. In the 60s, critical realism became the leading trend in literature, combining a realistic reflection of reality with interest in the individual. Prose takes first place compared to the previous period. Its brilliant examples were the works of I.S. Turgenev “Rudin”, “Fathers and Sons”, “On the Eve”, “The Noble Nest” and others, in which he showed the life of representatives of the noble society and the emerging common intelligentsia. I. A. Goncharov’s works “Oblomov”, “Cliff”, “Ordinary History” were distinguished by their subtle knowledge of life and the Russian national character. F. M. Dostoevsky, who in the 40s joined the Petrashevites, later revised his views and saw the solution to the problems facing Russia not in reforms or revolution, but in the moral improvement of man (novels “The Brothers Karamazov”, “Crime and Punishment” ", "Demons", "Idiot", etc.). L. Ya. Tolstoy, author of the novels “War and Peace”, “Anna Karenina”, “Resurrection”, etc., rethought Christian teaching in a unique way, developed the idea of the superiority of feelings over reason, combining harsh (and not always constructive) criticism of Russian society time with the idea of non-resistance to evil through violence. A. N. Ostrovsky depicted in his plays “The Dowry”, “The Thunderstorm”, “The Forest”, “Guilty Without Guilt” and others the lives of merchants, officials, and artists, showing interest in both purely social and eternal human issues. The outstanding satirist M. E. Saltykov-Shchedrin highlighted the tragic sides of Russian reality in “The History of a City,” “The Golovlev Gentlemen,” and “Fairy Tales.” A.P. Chekhov paid special attention in his work to the problem of the “little man” suffering from the indifference and cruelty of others. The works of V. G. Korolenko are imbued with humanistic ideas - “The Blind Musician”, “Children of the Dungeon”, “Makar’s Dream”.

F. I. Tyutchev continued the philosophical tradition in Russian poetry in his works. A. A. Fet dedicated his work to the celebration of nature. The poetry of N. A. Nekrasov, dedicated to the life of the common people, was extremely popular among the democratic intelligentsia.

Theater. The leading theater in the country was the Maly Theater in Moscow, on the stage of which P. M. Sadovsky, S. V. Shumsky, G. N. Fedotova, M. N. Ermolova played. The Alexandria Theater in St. Petersburg was also an important center of culture, where V.V. Samoilov, M.G. Savina, P.A. Strepetova played, however, being in the capital, it suffered more from interference from the authorities. Theaters emerge and develop in Kyiv, Odessa, Kazan, Irkutsk, Saratov, etc.

Music. The national traditions in Russian music, laid down by Glinka, were continued by his student A. S. Dargomyzhsky and the composers of the “Mighty Handful” (named so by V. V. Stasov, which included M. A. Balakirev, M. P. Mussorgsky, A. P. Borodin, N. A. Rimsky-Koreakov, Ts. A. Cui. One of the most outstanding composers of this period was P. I. Tchaikovsky, author of the operas "Eugene Onegin", "Mazeppa", "Iolanta", "The Queen of Spades" , ballets "Swan Lake", "Sleeping Beauty", "The Nutcracker". A conservatory was opened in St. Petersburg in 1862, and in Moscow in 1866. Choreographers M. Petipa and L. Ivanov played a huge role in the development of ballet.

Painting. Characteristic democratic ideas penetrated into the painting of the post-reform period, as evidenced by the activities of the Itinerants. In 1863, 14 students of the Academy of Arts refused the mandatory competition on the theme of German mythology, far from modern life, left the Academy and created the Artel of St. Petersburg Artists, which in 1870 was transformed into the Association of Traveling Art Exhibitions. Its members included portraitist I. N. Kramskoy, masters of genre painting V. G. Perov and Ya. A. Yaroshenko, landscape painters I. I. Shishkin and I. I. Levitan. V. M. Vasnetsov ("Alyonushka", “Ivan Tsarevich on the Gray Wolf”, “The Knight at the Crossroads”), V. I. Surikov dedicated his work to Russian history (“The Morning of the Streltsy Execution”, “Boyaryna Morozova”, “Menshikov in Berezovo”). I. E. Repin wrote both on modern (“Barge Haul Haulers on the Volga”, “Religious Procession in the Kursk Province”, “They Didn’t Expect”), and on historical topics (“Cossacks writing a letter to the Turkish Sultan”, “Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan”). The largest battle painter of that time was V.V. Vereshchagin (“Apotheosis of War”, “Mortally Wounded”, “Surrender!”). The creation of the Tretyakov Gallery, which exhibited a collection of paintings by the merchant-philanthropist P. M. Tretyakov, which he donated to the city of Moscow in 1892, played a major role in the popularization of Russian art. In 1898, the Russian Museum opened in St. Petersburg.

Sculpture. Prominent sculptors of that time were A. M. Opekushin (monuments to A. S. Pushkin, M. Yu. Lermontov, K. M. Baer), M. A. Antokolsky (“Ivan the Terrible”, “Peter I”, “Christ before people"), M. O. Mikeshin (monuments to Catherine II, Bogdan Khmelnitsky, supervision of work on the monument “Millennium of Russia”).

Architecture. The so-called Russian style was formed, imitating the decor of ancient Russian architecture. The buildings of the City Duma in Moscow (D. N. Chichagov), the Historical Museum in Moscow (V. O. Sherwood), and the Upper Trading Rows (now GUM) (A. N. Pomerantsev) were built in this manner. Residential buildings in large cities were built in the Renaissance-Baroque style with its characteristic richness of forms and decoration.

Family of Emperor Alexander III

Spouse. Alexander Alexandrovich received his wife, as well as the title of Tsarevich, “as an inheritance” from his elder brother, Tsarevich Nicholas. It was a Danish princess Maria Sophia Frederica Dagmara (1847-1928), in Orthodoxy Maria Feodorovna.

Nikolai Alexandrovich met his bride in 1864, when, having completed his home education, he went on a trip abroad. In Copenhagen, in the palace of the Danish king Christian XI, he was introduced to the royal daughter Princess Dagmara. The young people liked each other, but even without this their marriage was a foregone conclusion, as it corresponded to the dynastic interests of the Danish royal house and the Romanov family. The Danish kings had family connections with many of the royal houses of Europe. Their relatives ruled England, Germany, Greece and Norway. The marriage of the heir to the Russian throne with Dagmara strengthened the dynastic ties of the Romanovs with European royal houses.

On September 20, the engagement of Nikolai and Dagmara took place in Denmark. After this, the groom still had to visit Italy and France. In Italy, the Tsarevich caught a cold and began to have severe back pain. He reached Nice and there he finally went to bed. Doctors declared his condition threatening, and Dagmara went to the south of France with her queen mother, accompanied by Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich. When they arrived in Nice, Nikolai was already dying. The Tsarevich understood that he was dying, and he himself joined the hands of his bride and brother, asking them to get married. On the night of April 13, Nikolai Alexandrovich died from tuberculous inflammation of the spinal cord.

Alexander, unlike his father and grandfather, was not a great lover of women and a connoisseur of female beauty. But Dagmara, an eighteen-year-old beautiful graceful brown-haired woman, made a great impression on him. The new heir's falling in love with the bride of his deceased brother suited both the Russian imperial and Danish royal families. This means that he will not have to be persuaded into this dynastic union. But still, we decided to take our time and wait a little for the sake of decency with the new matchmaking. Nevertheless, in the Romanov family they often remembered the sweet and unhappy Minnie (as Dagmara was called Maria Feodorovna at home), and Alexander did not stop thinking about her.

In the summer of 1866, the Tsarevich began his trip to Europe with a visit to Copenhagen, where he hoped to see his dear princess. On the way to Denmark, he wrote to his parents: “I feel that I can and even really love dear Minnie, especially since she is so dear to us. God willing, everything will work out as I wish. I really don’t know what dear Minnie will say to all this; I don’t know her feelings towards me, and it really torments me. I'm sure we can be so happy together. I earnestly pray to God to bless me and ensure my happiness.”

The royal family and Dagmara received Alexander Alexandrovich cordially. Later, already in St. Petersburg, the courtiers said that the Danish princess did not want to miss the Russian imperial crown, so she quickly came to terms with replacing the handsome Nicholas, with whom she was in love, with the clumsy but kind Alexander, who looked at her with adoration. But what could she do when her parents decided everything for her long ago!

The explanation between Alexander and Dagmara took place on June 11, about which the newly minted groom wrote home on the same day: “I was already planning to talk to her several times, but I still didn’t dare, although we were together several times. When we looked at the photographic album together, my thoughts were not at all on the pictures; I was just thinking about how to proceed with my request. Finally I made up my mind and didn’t even have time to say everything I wanted. Minnie threw herself on my neck and began to cry. Of course, I also couldn’t help but cry. I told her that our dear Nyx prays a lot for us and, of course, is rejoicing with us at this moment. Tears kept flowing from me. I asked her if she could love anyone else besides dear Nyx. She answered me that there was no one except his brother, and again we hugged tightly. There was a lot of talk and reminiscing about Nix and his death. Then the queen, king and brothers came, everyone hugged us and congratulated us. Everyone had tears in their eyes."

On July 17, 1866, the young couple were engaged in Copenhagen. Three months later, the heir's bride arrived in St. Petersburg. On October 13, she converted to Orthodoxy with the new name Maria Feodorovna, and the grand ducal couple became engaged, and two weeks later, on October 28, they got married.

Maria Fedorovna quickly learned Russian, but until the end of her life she retained a slight, peculiar accent. Together with her husband, she made a slightly strange couple: he was tall, overweight, “masculine”; She is short, light, graceful, with medium-sized features of a pretty face. Alexander called her “beautiful Minnie”, was very attached to her and only allowed her to command him. It is difficult to judge whether she truly loved her husband, but she was also very attached to him and became his most devoted friend.

The Grand Duchess had a cheerful, cheerful character, and at first many courtiers considered her frivolous. But it soon became clear that Maria Fedorovna was extremely intelligent, had a good understanding of people and was able to judge politics sensibly. She turned out to be a faithful wife and a wonderful mother to her children.

Six children were born into the friendly family of Alexander Alexandrovich and Maria Feodorovna: Nikolai, Alexander, Georgy, Mikhail, Ksenia, Olga. The childhood of the Grand Dukes and Princesses was happy. They grew up surrounded by parental love and the care of specially trained nannies and governesses sent from Europe. At their service were the best toys and books, summer holidays in the Crimea and the Baltic Sea, as well as in the St. Petersburg suburbs.

But it did not at all follow from this that the children turned out to be spoiled sissies. Education in the Romanov family was traditionally strict and rationally organized. Emperor Alexander III considered it his duty to personally instruct the governesses of his offspring: “They should pray well to God, study, play, and be naughty in moderation. Teach well, don’t push, ask according to the full strictness of the laws, don’t encourage laziness in particular. If there is anything, then address it directly to me, I know what needs to be done, I repeat, I don’t need porcelain, I need normal, healthy, Russian children.”

All children, especially boys, were brought up in Spartan conditions: they slept on hard beds, washed with cold water in the morning, and received simple porridge for breakfast. Older children could be present with their parents and their guests at the dinner table, but they were served food last, after everyone else, so they did not get the best pieces.

The education of imperial children was designed for 12 years, 8 of which were spent on a course similar to the gymnasium. But Alexander III ordered not to torment the great princes and princesses with ancient languages that were unnecessary to them. Instead, natural science courses were taught, including anatomy and physiology. Russian literature, three major European languages (English, French and German) and world and Russian history were required. For physical development, children were offered gymnastics and dancing.

The emperor himself taught children traditional Russian games in the fresh air and the usual activities of a simple Russian person in organizing his life. His heir Nikolai Alexandrovich, being an emperor, enjoyed sawing wood and could light the stove himself.

Taking care of his wife and children, Alexander Alexandrovich did not know what dramatic future awaited them. The fate of all the boys was tragic.

Grand Duke Nikolai Alexandrovich (05/06/1868-16(07/17/1918)- heir to the throne, the future Emperor Nicholas II the Bloody (1894-1917), became the last Russian Tsar. He was overthrown from the throne during the February bourgeois revolution of 1917 and in 1918, along with his entire family, was shot in Yekaterinburg.

Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich (1869-1870)- died in infancy.

Grand Duke Georgy Alexandrovich (1871-1899)- Heir-Tsarevich under his elder brother Nicholas II in the absence of male children. Died of consumption (tuberculosis).

Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich (1878-1918)- Heir-Tsarevich under his elder brother Nicholas II after the death of his brother Georgy Alexandrovich and before the birth of Grand Duke Alexei Nikolaevich. In his favor, Emperor Nicholas II abdicated the throne in 1917. He was shot in Perm in 1918.

To the wife of Alexander III Maria Feodorovna and daughters Grand Duchess Ksenia Alexandrovna (1875-1960) who was married to her cousin Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, And Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna (1882-1960) managed to escape abroad.

But in those days when Alexander Alexandrovich and Maria Feodorovna were happy with each other, nothing foreshadowed such a tragic outcome. Parental care brought joy, and family life was so harmonious that it formed a striking contrast with the life of Alexander II.

The heir-Tsarevich managed to look convincing when he demonstrated an even, respectful attitude towards his father, although in his soul he could not forgive him for betraying his sick mother for the sake of Princess Yuryevskaya. In addition, the presence of a second family for Alexander II could not but unnerve his eldest son, as it threatened to disrupt the order of succession to the throne in the Romanov dynasty. And although Alexander Alexandrovich could not condemn his father openly and even promised him after his death to take care of Princess Yuryevskaya and her children, after the death of his parent he tried to quickly get rid of the morganatic family by sending him abroad.

According to the status of the heir, Alexander Alexandrovich was supposed to be engaged in a variety of government activities. He himself most liked things related to charity. His mother, Empress Maria Alexandrovna, a famous philanthropist, managed to instill in her son a positive attitude towards helping the suffering.

By coincidence, the heir's first position was the post of chairman of the Special Committee for the collection and distribution of benefits to the hungry during the terrible crop failure of 1868, which befell a number of provinces in central Russia. Alexander's activity and management in this position immediately brought him popularity among the people. Even near his residence, the Anichkov Palace, a special mug for donations was displayed, into which St. Petersburg residents daily put from three to four thousand rubles, and on Alexander’s birthday there were about six thousand in it. All these funds went to the starving people.

Later, mercy for the lower strata of society and sympathy for the hardships of their lives would find expression in the labor legislation of Emperor Alexander III, which stood out for its liberal spirit against the background of other political and social initiatives of his time.

The Grand Duke's mercy impressed many. F. M. Dostoevsky wrote about him in 1868: “How glad I am that the heir appeared before Russia in such a good and majestic form, and that Russia thus testifies to her hopes for him and her love for him. Yes, even half the love I have for my father would be enough.”

Mercy may have also dictated the Tsarevich's peacefulness, which was unusual for a member of the Romanov family. He took part in the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878. Alexander did not show any special talents at the theater of war, but he acquired a strong conviction that war brings incredible hardships and death to the ordinary soldier. Having become emperor, Alexander pursued a peacemaking foreign policy and in every possible way avoided armed conflicts with other countries, so as not to shed blood in vain.

At the same time, some of Alexander’s actions are an excellent illustration of the fact that loving and pitying all of humanity often turns out to be simpler and easier than respecting an individual person. Even before the start of the Russian-Turkish war, the heir had an unpleasant quarrel with a Russian officer of Swedish origin, K. I. Gunius, who was sent by the government to America to purchase guns. Alexander Alexandrovich did not like the samples brought. He harshly and rudely criticized the choice. The officer tried to object, then the Grand Duke shouted at him, using vulgar expressions. After his departure from the palace, Gunius sent the Tsarevich a note demanding an apology, and otherwise threatened to commit suicide in 24 hours. Alexander considered all this stupidity and did not think to apologize. A day later the officer was dead.

Alexander II, wanting to punish his son for his callousness, ordered him to follow Gunius’ coffin to the grave. But the Grand Duke did not understand why he should have felt guilty for the suicide of an overly scrupulous officer, since rudeness and insults towards subordinates were practiced by the male part of the Romanov family.

Among Alexander Alexandrovich’s personal interests, one can highlight his love for Russian history. He contributed in every possible way to the founding of the Imperial Historical Society, which he himself headed before ascending the throne. Alexander had an excellent historical library, which he replenished throughout his life. He gladly accepted historical works brought to him by the authors themselves, but, carefully arranging them on the shelves, he rarely read. He preferred the historical novels of M. N. Zagoskin and I. I. Lazhechnikov to scientific and popular books on history and judged Russia’s past from them. Alexander Alexandrovich had a special curiosity about the past of his family and wanted to know how much Russian blood flowed in his veins, since it turned out that on the female side he was more likely German. The information extracted from the memoirs of Catherine II that her son Paul I could have been born not from her legal husband Peter III, but from the Russian nobleman Saltykov, oddly enough, pleased Alexander. This meant that he, Alexander Alexandrovich, was more Russian in origin than he had previously thought.

From fiction, the Tsarevich preferred the prose of Russian writers of the past and his contemporaries. The list of books he read, compiled in 1879, includes works by Pushkin, Gogol, Turgenev, Goncharov and Dostoevsky. The future emperor read “What to do?” Chernyshevsky, became acquainted with illegal journalism published in foreign emigrant magazines. But in general, Alexander was not an avid bookworm, reading only what a very averagely educated person of his time could not do without. In his leisure hours, he was occupied not by books, but by theater and music.

Alexander Alexandrovich and Maria Fedorovna visited the theater almost weekly. Alexander preferred musical performances (opera, ballet), and did not disdain operetta, which he attended alone, since Maria Feodorovna did not like her. Amateur performances were often staged in the Anichkov Palace of the Grand Duke, in which family members, guests, and children’s governesses played. The directors were professional actors who considered it an honor to work with the heir's troupe. Alexander Alexandrovich himself often played music at home concerts, performing simple works on the horn and bass.

The Tsarevich was also famous as a passionate collector of works of art. He himself was not very well versed in art and preferred portraits and battle paintings. But in his collections, which filled the Anichkov Palace and chambers in the imperial residences that belonged to him, there were works by the Itinerants, whom he disliked, and works by old European masters and modern Western artists. As a collector, the future emperor relied on the taste and knowledge of connoisseurs. On the advice of Pobedonostsev, Alexander also collected ancient Russian icons, which formed a separate, very valuable collection. In the 1880s. The Grand Duke purchased for 70 thousand rubles a collection of Russian paintings by gold miner V. A. Kokorev. Subsequently, the collections of Alexander III formed the basis of the collection of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

The serene life of the Tsarevich's family, slightly overshadowed only by the presence of his father's morganatic family, ended on March 1, 1881. Alexander III, from the age of twenty, was preparing to reign for sixteen years, but did not imagine that the throne would go to him so unexpectedly and in such tragic circumstances.

Already on March 1, 1881, Alexander received a letter from his teacher and friend, Chief Prosecutor of the Synod K. P. Pobedonostsev, which said: “You are getting a Russia that is confused, shattered, confused, yearning to be led with a firm hand, so that the ruling the authorities saw clearly and knew firmly what they wanted and what they did not want and would not allow in any way.” But the new emperor was not yet ready for firm, decisive actions and, according to the same Pobedonostsev, in the first days and weeks of his reign he looked more like a “poor sick, stunned child” than a formidable autocrat. He wavered between his desire to fulfill his earlier promises to his father to continue reforms and his own conservative ideas about what the power of the emperor should look like in autocratic Russia. He was haunted by the anonymous message he received immediately after the terrorist attack that ended the life of Alexander II, which stood out among the sympathetic condolences, which, in particular, stated: “Your father is not a martyr or a saint, because he suffered not for the church, not for the cross, not for the Christian faith, not for Orthodoxy, but for the sole reason that he dissolved the people, and this dissolved people killed him.”

The hesitation ended by April 30, 1881, when a manifesto was born that defined the conservative-protective policy of the new reign. Conservative journalist M.N. Katkov wrote about this document: “Like manna from heaven, the people's feelings were waiting for this royal word. It is our salvation: it returns the Russian autocratic Tsar to the Russian people.” One of the main compilers of the manifesto was Pobedonostsev, who took as a model the Manifesto of Nicholas I of December 19, 1815. People knowledgeable in politics again saw the shadow of Nicholas’s reign, only the place of a temporary worker, as Arakcheev and Benckendorff had been in their time, was now taken by another person . As A. Blok wrote, “Pobedonostsev spread his owl’s wings over Russia.” Modern researcher V.A. Tvardovskaya even saw special symbolism in the fact that the beginning of the reign of Alexander III was marked by the execution of five Narodnaya Volya members, while the reign of Nicholas I began with the execution of five Decembrists.

The manifesto was followed by a series of measures repealing or limiting the reform decrees of the previous reign. In 1882, new “Temporary Rules on the Press” were approved, which lasted until 1905, putting all press and book publishing in the country under government control. In 1884, a new university charter was introduced, which virtually destroyed the autonomy of these educational institutions and made the fate of teachers and students dependent on their loyalty to the authorities. At the same time, the fee for obtaining higher education has doubled, from 50 to 100 rubles per year. In 1887, the infamous “cook’s children” circular was adopted, which recommended limiting the admission to the gymnasium of children of domestic servants, small shopkeepers, artisans and other representatives of the lower classes. In order to maintain public peace, even the celebration of the 25th anniversary of the abolition of serfdom was prohibited.

All these measures did not give the imperial family confidence in their own safety. The public regicide, organized by the People's Will, instilled fear in the Winter Palace, from which its inhabitants and their immediate circle could not get rid of.