Methods of zoopsychological research methods of zoopsychology methods of zoopsychology. Experimental method in animal psychology Observation method in animal psychology description

In zoopsychological research methods:

1. The "labyrinth" method. The experimental animal is given the task of finding a path to a specific goal that is not directly perceived by it (food or shelter). The experiments use both two-dimensional, one-level mazes, where the animal moves in one plane, and three-dimensional, two-level mazes, where the animal can move in two planes. When deviating from the right path, animal punishment is sometimes used. The results of an animal's passage through a maze are determined, as a rule, by the speed of reaching the “goal” and by the number of mistakes made. This method allows us to study the ability of animals to learn, to develop motor skills, as well as the ability to spatial orientation.

2. The "workaround" method. Feature - the animal directly perceives the object towards which its actions are directed already at the beginning of the experience. Usually this object is food. Unlike the “maze” method, in this method the animal has to go around one or more obstacles to reach the object. In experiments using the workaround method, the speed and trajectory of the animal’s movement, the degree of complexity of the task, and the speed of its solution when the animal searches for a workaround and achieves the result are taken into account and assessed.

3. Method of "differentiation training". used to identify an animal’s ability to distinguish objects and their characteristics, while the objects are presented simultaneously or sequentially. When the object is chosen correctly, the animal is rewarded, this method is called positive training; in other cases, simultaneously with the reinforcement of the correct choice, punishment is applied for the wrong choice, this method is called positive-negative training. By consistently reducing the differences between the characteristics of objects, the researcher can identify in an animal the limits of discrimination (differentiation) of a given quality of objects. In this way, the peculiarities of vision in animals of different species are studied (acuity, color perception, perception of sizes and shapes), the processes of formation of skills, the memory of animals (based on the time of storage of training results), as well as the ability of animals to generalize.

4. “Sample selection” method. This method is a variant of the differential training method and is used to study the sensory systems of higher animals (monkeys). The animal must choose from a number of objects the object that matches the sample. The sample is presented to the animal at the beginning of the experiment, and the correct choice is usually positively reinforced during the experiment.

5. The “problem cell (box)” method. In experiments where this method is used, the animal must open (sometimes in a certain sequence) the gates on the cage door or box lid in order to receive reinforcement (food or freedom). This method makes it possible to study complex forms of learning and motor elements of the intellectual behavior of animals. The use of this method is especially productive when studying animals with developed grasping limbs (rats, raccoons, monkeys). When setting up experiments to identify the higher mental abilities of animals, they are usually given the opportunity to use various tools (sticks, blocks, etc.) to solve the problem. Using this method, with a gradual complication of the task, in the process of experiments, it is possible to obtain valuable data not only on the effector, but also on the sensory components of animal intelligence.

6. A method for analyzing ordinary, non-reinforced manipulation of various objects. This research method makes it possible to judge the effector abilities of animals, their orientation-research activities, play behavior, abilities for analysis and synthesis, and also allows us to trace the background of human labor activity.

In addition, it should be noted that in all zoopsychological studies, the results of observations are usually recorded using photography, film and video, sound recording and other means of recording animal behavior.

-

zoopsychology And comparative psychology

IN zoopsychological research the most commonly used are the following methods -

Methods research V zoopsychology And comparative psychology. IN zoopsychological research the most commonly used are the following methods: 1. Method"L...more details." -

Methods research V zoopsychology And comparative psychology. IN zoopsychological research the most commonly used are the following methods -

Methods research V zoopsychology And comparative psychology. IN zoopsychological research the most commonly used are the following methods -

Item zoopsychology And comparative psychology.

Special area - studying animal intelligence. Sometimes comparative psychology perceived as method, and not an independent science. -

Just download the cheat sheets zoopsychology And comparative psychology

Animal intelligence and methods his studying. -

Home / Zoopsychology And comparative psychology/ Answers to questions about zoopsychology. “Previous question. Animal intelligence and methods his studying. -

Just download the cheat sheets zoopsychology And comparative psychology- and you are not afraid of any exam! Community.

In the middle of the 20th century, anthropomorphism received a new development, which was due to the beginning of extensive research sea... -

Just download the cheat sheets zoopsychology And comparative psychology- and you are not afraid of any exam!

1. Representatives of reflexology - I.P. Pavlov (author method development of classical conditioned reflexes, as well as theories about the type of GNI), Edward Thorndike... -

Just download the cheat sheets zoopsychology And comparative psychology- and you are not afraid of any exam! Community.

Animal intelligence and methods his studying.

Similar pages found:10

As already indicated, materialistic zoopsychology proceeds in its scientific search from the fact that the basis for the source of mental reflection in animals is their behavior, “animal practice.” The qualitative difference between the latter and human practice is that animals do not rise above the level of general adaptive objective activity, while in humans, the highest, productive form of objective activity, inaccessible to animals, is of decisive importance - labor. At the same time psychological analysis of specific forms of motor activity of animals, the structure of their actions, acts of their behavior, aimed at individual components of the environment, gives a clear idea of certain mental qualities and processes.

A specific psychological analysis of an animal’s behavior is carried out by an animal psychologist through a detailed study of the movements of the experimental animal in the course of solving certain problems. These tasks are set so that the movements of the animal can be used to judge the mental quality being studied with the greatest accuracy. At the same time, the physiological state of the animal, the external conditions under which the experiment is carried out, and in general all significant factors that can influence the result of the experiment must be taken into account.

An important role is played in zoopsychological research and observation of animal behavior in natural conditions. Here it is important to trace the changes that occur in the behavior of the animal during certain changes in the environment. This allows us to judge both the external causes of mental activity and the adaptive functions of the latter. Both in laboratory and field conditions, a researcher’s highly developed observational skills are the most important key to the success of his work.

Although the study of the structure of an animal’s behavior primarily involves a qualitative assessment of its activity, inaccurate quantitative assessments are of considerable importance in animal psychological research. This refers to the characteristics of both the behavior of the animal and external conditions (environmental parameters).

An example of a skillful combination of observation and experiment, quantitative and qualitative analysis of animal behavior can be found in the scientific work of the outstanding Soviet zoopsychologist N. N. Ladygina-Kots. So, for example, back in 1917-1919. She studied the motor skills of macaque monkeys using the "problem cage" method, that is, an experimental setup equipped with locking mechanisms that the animal had to unlock. The researchers who used this method before her were essentially only interested in the speed of solving the problem and the “ceiling” of the animal’s capabilities as the experimental situation gradually became more complex. Ladygina-Kots used the “problem cell” for a fundamentally different purpose - to understand the psyche of the monkey, to study its motor and cognitive abilities. And therefore, during the experiment, she followed not only the movement of the stopwatch hand, but primarily the movements of the experimental animal’s hands, realizing that these movements were directly related to the “mental life” of the monkey.

Already in those years, while still a young scientist, Ladygina-Kots was looking for manifestations of the psyche in the characteristics of the animal’s motor activity, in specific forms of influence on the objects around it. And in her subsequent works, she convincingly showed that an animal psychologist should study not so much what an animal does, but how it does it. Therefore, Ladygina-Kots warned about the danger of infringing on the motor activity of the animal under study, limiting its initiative and artificially imposing certain movements, as this inevitably leads to distorted or even incorrect conclusions, and at the same time to the loss of the most valuable information about the mental qualities of the animal. In this regard, Ladygina-Kots always treated with due caution the results of studying the mental activity of animals in laboratory experimental conditions alone, clearly saw the limits of the possibilities of its application and supplemented her own experimental data with the results of observations of free, non-imposed animal behavior.

A very important point in zoopsychological research is also taking into account the biological adequacy of the experimental conditions and the methodology used. If an experiment is carried out without taking into account the specific biology of the species being studied and the natural behavior of a given animal in an experimentally simulated life situation, then the result of the study will be distorted and can easily turn out to be an artifact, as the following example shows.

Almost at the same time, in 1913-1914, two outstanding researchers of animal behavior, K. Hess and K. Frisch, studied the ability of bees to distinguish colors. Hess released the bees in a dark room, where they could fly to two light sources - different colors and different lightness. Using various combinations, the scientist found that bees always fly to a lighter source, regardless of wavelength. From this he concluded that bees do not distinguish colors.

Frisch, having structured the experiment differently, came to the exact opposite conclusion. In his experiments, bees were asked to choose colored (for example, yellow) pieces of paper in the light among white, black and gray various shades, which equalized the color intensity of reinforced colored and non-reinforced achromatic papers. The bees unerringly found yellow (or other colors) squares of paper reinforced with syrup, regardless of the lightness and saturation of their color, leaving achromatic sheets unnoticed. The mother-in-law's ability to sense color has been proven.

Hess's mistake was that he conducted experiments in conditions that were biologically inadequate for bees - in the Dark. Under these conditions, those forms of behavior in which color perception plays some role cannot appear, for example, when searching for food objects. Once in a dark room during the day, a bee will only look for a way out of it. At the same time, it will naturally rush to the lighter hole, regardless of the color of the light rays entering through it. Thus, the results obtained by Hess cannot indicate the presence or absence of color perception in bees and therefore cannot be used to solve the question posed.

This clearly reveals the fact that the reactions of animals to the same external stimuli can be very different in different life situations and functional areas. In this example, bees respond to colors in one situation, but not in another. Moreover, in one case (in the area of feeding behavior) bees react only to color, in another (in the area of defensive behavior) - only to the intensity of lighting, completely ignoring the color component. All this indicates the exceptional complexity of experimental zoopsychological research and the importance of creating biologically adequate conditions for conducting experiments.

Specific methods of zoopsychological experimental research are very diverse, although all of them, as already mentioned, boil down to setting certain tasks for the animal. Here are just a few basic methods.

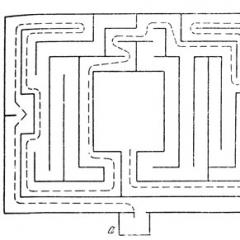

The "labyrinth" method. The experimental animal is given the task of finding a path to a specific “goal” that is not directly perceived by it, which is most often food bait, but may also be a shelter (“home”) or other favorable conditions. If the animal deviates from the correct path, in some cases the animal may be punished. In its simplest form, a labyrinth looks like a T-shaped corridor or tube. In this case, when turning in one direction, the animal receives a reward; when turning in the other, it is left without a reward or even punished. More complex labyrinths are made up of different combinations of T-shaped (or similar) elements and dead ends, entry into which is regarded as an animal error (Fig. 1). The results of an animal's passage through a maze are determined, as a rule, by the speed of reaching the “goal” and by the number of mistakes made.

Rice. 1. Labyrinths: a) plan of the first labyrinth used in zoopsychological research (Small’s labyrinth); b) a labyrinth of “bridges”

The “labyrinth” method makes it possible to study both issues related directly to the ability of animals to learn (to develop motor skills), and issues of spatial orientation, in particular the role of the skin-muscular and other forms of sensory, memory, and the ability to transfer motor skills to new conditions , to the formation of sensory generalizations, etc.

Most of the above issues are also being studied "workaround" method. In this case, the animal has to bypass one or more obstacles to achieve the “goal” (Fig. 2).

Rice. 2. Conducting experiments using the “workaround” method (according to Fischel)

Unlike the “labyrinth” method, in this case the animal directly perceives the object (bait) towards which its actions are directed already at the beginning of the experiment. The speed and trajectory of movement are taken into account and evaluated when searching for a workaround around an obstacle. In a slightly modified form, L. V. Krushinsky used the “workaround” method to study the ability of different animals to extrapolate. (These experiments will be described below.)

Differential training is aimed at identifying the ability of an experimental animal to distinguish between simultaneously or sequentially presented objects and their signs (Fig. 3). Choice - the animal is rewarded with one of the objects presented in pairs (or in a larger number) (positive training), in other cases, simultaneously with the reinforcement of the correct choice, the wrong one is punished (positive-negative training). By consistently reducing the differences between the characteristics of objects (for example, their sizes), it is possible to identify the limits of discrimination (differentiation). In this way, it is possible to obtain information characterizing, for example, the features of vision in the animal species being studied (its acuity, color perception, perception of sizes and shapes, etc.).

The same method is used to study the processes of skill formation (in particular, to various combinations of stimuli), the memory of animals (by checking the retention of training results after a certain period of time), and the ability to generalize. In the latter case, as a rule, the dissimilarity of sequentially presented objects (figures) is gradually increased, revealing the animal’s ability to navigate by individual common features of these objects.

A variant of differential training, applicable only to higher animals, is sample selection method. The animal is asked to make a choice among a number of objects, guided by a sample that is shown to it directly by the experimenter or in a special apparatus. The right choice is reinforced. This method is also mainly used to study the sensory sphere of animals.

"Problem cell" (box) method. The animal is given the task of either discovering a way out of the cage by activating various devices (levers, pedals, bolts, etc.), or, conversely, entering the cage where the food is located by unlocking the locking devices. Sometimes small boxes or caskets with closures are used, the unlocking of which gives the experimental animal access to food. In a more complex experiment, all mechanisms and devices operate only in a strictly defined sequence, which must be learned and remembered by the animal. This method studies complex forms of learning and motor elements of the intellectual behavior of animals. It is especially convenient to use this method, naturally, for studying animals with developed grasping limbs - rats, raccoons, monkeys, etc. This also applies to setting up experiments in which animals have to use guns to achieve complementary feeding. These experiments also serve primarily to reveal the higher mental abilities of animals.

Elements of instrumental actions are clearly evident already in experiments using a bait tied to a rope: an animal can take possession of a food object only by pulling it towards itself by the rope. By complicating the situation with different combinations of ropes and varying their relative positions, it is possible to obtain valuable data not only on the effector, but also on the sensory (visual and tactile) components of animal intelligence.

Most often, sticks (simple or compound) are used as a weapon in experiments, with the help of which animals (usually monkeys) can push or knock down a food object. Boxes and other objects are widely used in experiments with monkeys (especially apes), from which they must build “pyramids” to reach a high-hanging fetus. And in this case, the analysis of the structure of the animal’s objective activity in the course of solving the problem is of greatest importance.

Along with such more or less complex experiments, the analysis of ordinary, non-reinforced manipulation various items. Such studies make it possible to judge the effector abilities of animals, their orientation-research activities, play behavior, abilities for analysis and synthesis, etc., and also shed light on the prehistory of human labor activity.

In all animal psychological research, photography and filming, sound recording and other means of recording animal behavior are widely used. However, no technical means can replace the keen eye of a researcher and a living human mind, on which success in working with animals primarily depends.

Method of using tools

Analysis of unreinforced manipulation

9. Some features of modern

“history and theories of zoopsychology”

Similar material:

- Methodological recommendations for organizing independent work, 458.16kb.

- Methodological recommendations for organizing independent educational work for students, 419.88kb.

- Methodological recommendations for independent work of students in the discipline “Social, 367.42kb.

- Methodological recommendations for performing independent work for students studying 597.82kb.

- Problems of increased complexity in the discipline “descriptive geometry” Methodological recommendations, 151.04kb.

- Methodological recommendations for independent work of distance learning students, 294.83kb.

- Guidelines for students, recommendations for organizing independent work, 49.13kb.

- Methodological recommendations for independent work on the course “Financial accounting, 688.99kb.

- Methodological recommendations for students of the 5th medical and 6th pediatric faculties, 367.46kb.

- Methodological recommendations Minsk 2002 udk 613. 262 (075. , 431.6kb.

zoopsychological research

Animal psychology methods- methods of studying animal behavior, including experiment And observation. Observations of the natural behavior of animals in their habitats are supplemented by the study of their attitude to various objects, partly specially selected by the experimenter, which are sometimes presented to the experimental animal in artificially created situations; forms are analyzed manipulation these items.

Materialistic animal psychology proceeds in its scientific research from the fact that the basis and source of mental reflection in animals is their behavior

(according to A.N. Leontiev, behavior is the source of knowledge about the psyche), “animal practice.”

Example 1. Moving along the obstacle, the rat in its movements resembles the objective metric of the environment. Through this the reflection of the environment occurs. A new, unfamiliar place (square field) has a negative meaning. The animal “freezes” (freezing). The degree of his activity (urination, defecation) determines his emotionality. Based on how the behavior of a rat changes in an open field, conclusions can be drawn about how it reflects the environment. The rat moves slowly, crawling, feeling the walls with its whiskers. One round is enough to reflect the field. If at a certain place (A) the animal making the first circle is frightened, the rat will return to the beginning of the circle. If she is already familiar with the area, she will run forward along the wall (or, taking a shortcut, through the middle). We can conclude what exactly the animal reflected.

Example 2. New objects are placed in the center of the floor the rat has already explored. The animal feels them with whiskers: by touching the surface, the rat determines its character. She grabs soft objects with her teeth and bites hard ones. Then he turns the object and gnaws it. By the nature of the actions one can determine how it reflects the subject. If it is a wire that makes a sound when it falls, the rat again performs the action that caused the sound. Having learned to roll a pebble, the rat shows that it has reflected its ability to roll.

Research occupies an important place in animal psychology manipulative activity animals - impact on the environment with the help of limbs. Through their actions, animals reflect the properties of the objects they study.

Example 3(observations by Nadezhda Nikolaevna Ladygina-Kots). The primate builds a nest; various materials are placed on it. The animal uses them in accordance with their properties. The chimpanzee carries pine branches carefully so as not to get dirty. The monkey carries the plywood on his back with his arms outstretched. Sawdust collects in the retracted stomach. When from a variety of objects it is necessary to choose something with which to wipe his eyes, the chimpanzee always chooses the thinnest paper napkins to scratch his back and uses bumps.

The qualitative difference between “animal practice” and human practice is that animals do not rise above the level of general adaptive objective activity, while in humans, the highest, productive form of objective activity, inaccessible to animals, is of decisive importance - labor. At the same time, psychological analysis of specific forms of motor activity of animals, the structure of their actions, acts of their behavior aimed at individual components of the environment, gives a clear idea of certain mental qualities or processes. By analyzing the behavior of animals, we can draw a conclusion about what characteristics of the environment they reflect, depending on the type of behavior.

Fundamental features of zoopsychological research

1. A specific psychological analysis of an animal’s behavior is carried out by an animal psychologist through a detailed study of the movements of the experimental animal in the course of solving certain problems.

These tasks are set so that the movements of the animal can be used to judge the mental quality being studied with the greatest accuracy. At the same time, the physiological state of the animal, the external conditions under which the experiment is carried out, and in general all significant factors that can influence the result of the experiment must be taken into account.

2. An important role is played in zoopsychological research and observation of animal behavior in natural conditions.

Here it is important to trace the changes that occur in the behavior of the animal during certain changes in the environment. This allows us to judge both the external causes of mental activity and the adaptive functions of the latter. Both in laboratory and field conditions, a researcher’s highly developed observational skills are the most important key to the success of his work.

3. Studying the structure of an animal’s behavior involves, first of all, a qualitative assessment of its activity, but accurate quantitative assessments are also of considerable importance.

This refers to the characteristics of both the behavior of the animal and external conditions (environmental parameters). According to N.N. Ladygina-Kotts, a zoopsychologist should study not so much what an animal does, but how it does it.

An example of a skillful combination of observation and experiment, quantitative and qualitative analysis of animal behavior can be found in the scientific work of the outstanding Soviet zoopsychologist N.N. Ladygina-Cats. So, for example, back in 1917-1919. she studied the motor skills of macaque monkeys using the “problem cell” method, i.e. experimental setup equipped with locking mechanisms that the animal had to unlock. The researchers who used this method before her were essentially only interested in the speed of solving the problem and the “ceiling” of the animal’s capabilities as the experimental situation gradually became more complex. Ladygina-Kots used the “problem cell” for a fundamentally different purpose - to understand the psyche of the monkey, to study its motor and cognitive abilities. And therefore, during the experiment, she followed not only the movement of the stopwatch hand, but, above all, the movements of the hands of the experimental animal, realizing that these movements were directly related to the “mental life” of the monkey.

Already in those years, while still a young scientist, Ladygina-Kots was looking for manifestations of the psyche in the characteristics of the animal’s motor activity, in specific forms of influence on the objects around it. And in her subsequent works, she convincingly showed that an animal psychologist should study not so much what the animal does, but what How it does it. Therefore, Ladygina-Kots warned about the danger of infringing on the motor activity of the animal under study, limiting its initiative and artificially imposing certain movements, as this inevitably leads to distorted or even incorrect conclusions, and at the same time to the loss of the most valuable information about the mental qualities of the animal. In this regard, Ladygina-Kots always treated with due caution the results of studying the mental activity of animals in laboratory experimental conditions alone, clearly saw the limits of the possibilities of its application and supplemented her own experimental data with the results of observations of free, non-imposed animal behavior.

4. An important point in zoopsychological research is also taking into account the biological adequacy of the experimental conditions and the methodology used.

If the experiment is carried out without taking into account the specific features of the biology of the species being studied and the natural behavior of this animal in an experimentally simulated life situation, then the result of the study will be distorted and can easily turn out to be an artifact, as the following example shows.

Almost at the same time, in 1913-1914, two outstanding researchers of animal behavior, K. Hess and K. Frisch, studied the ability of bees to distinguish colors. Hess released the bees in a dark room, where they could fly to two light sources - different colors and different lightness. Using various combinations, the scientist found that bees always fly to a lighter source, regardless of wavelength. From this he concluded that bees do not distinguish colors.

Frisch, having structured the experiment differently, came to the exact opposite conclusion. In his experiments, bees were asked to choose colored (for example, yellow) pieces of paper in the light among white, black and gray various shades, which equalized the color intensity of reinforced colored and non-reinforced achromatic papers. The bees unerringly found yellow (or other colors) squares of paper reinforced with syrup, regardless of the lightness and saturation of their color, leaving achromatic sheets unnoticed. Thus, the ability of bees to sense color was proven.

Hess's mistake was that he conducted experiments in conditions that were biologically inadequate for bees - in the dark. Under these conditions, those forms of behavior in which color perception plays some role cannot appear, for example, when searching for food objects. Once in a dark room during the day, a bee will only look for a way out of it. At the same time, it will naturally rush to the lighter hole, regardless of the color of the light rays entering through it. Thus, the results obtained by Hess cannot indicate the presence or absence of color perception in bees and therefore cannot be used to solve the question posed.

This clearly reveals the fact that the reactions of animals to the same external stimuli can be very different in different life situations and functional areas. In this example, bees respond to colors in one situation, but not in another. Moreover, in one case (in the area of feeding behavior) bees react only to color, in another (in the area of protective behavior) - only to the intensity of lighting, completely ignoring the color component.

All of the above indicates the exceptional complexity of experimental zoopsychological research and the importance of creating biologically adequate conditions for conducting experiments. Specific methods of zoopsychological experimental research are very diverse, although all of them, as already mentioned, traditionally come down to setting certain tasks for the animal. Let us consider the main methods of zoopsychology, traditionally used to study the behavior of animals as part of setting certain tasks for them.

8. Characteristics of traditional methods of zoopsychology,

reduced to setting tasks for animals

Using these methods, the behavior of animals is studied for the purpose of a detailed analysis of the movement of animals in the simplest situations organized by the researcher and, on the basis of this analysis, the study of sensory and effector abilities, orientation-exploratory behavior, emotions, memory of animals, their ability to learn (for animal psychology, acquired features), generalization and transfer of individual experience, to intellectual actions, etc. For this kind of research, animals bred in the laboratory are usually used. Animal psychology examines the process of interaction between an animal and its environment under easily controlled conditions. Knowing the animal’s past experience and placing it in a new situation, the animal psychologist studies the characteristics of the animal’s reflection of the environment.

Maze method

(finding a way to what is not directly perceived

target object - food, shelter, etc.)

SMALL was invented by Albion Woodbury (1854-1926), an American sociologist and representative of social Darwinism. Founder of the American Journal of Sociology (1895), head of the world's first sociological department (since 1892) at the University of Chicago. The experimental animal is given the task of finding a path to a specific “goal” that is not directly perceived by it, which is most often food bait, but may also be a shelter (“home”) or other favorable conditions. If the animal deviates from the correct path, in some cases the animal may be punished. In its simplest form, a labyrinth looks like a T-shaped corridor or tube. In this case, when turning in one direction, the animal receives a reward; when turning in the other, it is left without a reward or even punished. More complex labyrinths are made up of different combinations of T-shaped (or similar) elements and dead ends, entry into which is regarded as an animal error. The results of an animal's passage through a maze are determined, as a rule, by the speed of reaching the “goal” and by the number of mistakes made.

"Maze" method allows you to study both issues related directly to the ability of animals to learn (to develop motor skills), and issues of spatial orientation, in particular the role of skin-muscular and other forms of sensitivity, memory, the ability to transfer motor skills to new conditions, to the formation of sensory generalizations, etc.

WORKBACK METHOD

(finding a path to a perceived target object

bypassing one or more obstacles)

In this case, the animal has to bypass one or more obstacles to achieve the “goal”. Unlike the “labyrinth” method, in this case the animal directly perceives the object (bait) towards which its actions are directed already at the beginning of the experiment. The speed and trajectory of movement are taken into account and assessed when searching for a workaround around an obstacle.

Using this method, most of the issues listed above are studied.

In a slightly modified form, L.V. Krushinsky used the “workaround” method to study the ability of different animals to extrapolations.

SIMULTANEOUS OR SEQUENTIAL SELECTION METHOD,

or Differential training

(selection of objects - signals, pictures, etc. - differing in one

or several, sometimes changing characteristics)

The method is aimed at identifying the ability of an experimental animal to distinguish simultaneously or sequentially presented objects and their characteristics. The animal’s choice of one of pairwise (or more) presented objects is rewarded (positive training); in other cases, simultaneously with the reinforcement of the correct choice, the wrong choice is punished (positive-negative training). By consistently reducing the differences between the characteristics of objects (for example, their sizes), it is possible to identify the limits of discrimination (differentiation).

Using this method, it is possible to obtain information characterizing, for example, the visual characteristics of the animal species being studied (its acuity, color perception, perception of sizes and shapes, etc.). The same method is used to study skills formation processes(in particular, to various combinations of stimuli), animal memory(by checking the retention of training results after a certain period of time), generalization ability. In the latter case, as a rule, the dissimilarity of sequentially presented objects (figures) is gradually increased, revealing the animal’s ability to navigate by individual common features of these objects.

sample selection method

(choice among objects, while a sample is presented)

It is a variant of differential training, applicable only to higher animals. . The animal is asked to make a choice among a number of objects, guided by a sample that is shown to it directly by the experimenter or in a special apparatus. The right choice is reinforced.

The method is used primarily to study animal sensory sphere.

OPEN FIELD METHOD

(providing the animal with the opportunity to freely choose a path and location in a space enclosed by walls and, if necessary, complicated by structural components - objects, shelters, etc.);

Problem cell (box) method

(finding the possibility of exiting or entering the cage by opening more or less complex locking devices)

The animal is given the task of either discovering a way out of the cage by activating various devices (levers, pedals, bolts, etc.), or, conversely, entering the cage where the food is located by unlocking the locking devices. Sometimes small boxes or caskets with closures are used, the unlocking of which gives the experimental animal access to food. In a more complex experiment, all mechanisms and devices operate only in a strictly defined sequence, which must be assimilated and remembered by the animal.

This method complex forms of learning and motor elements of the intellectual behavior of animals are studied. It is especially convenient to use this method, naturally, for studying animals with developed grasping limbs - rats, raccoons, monkeys, etc. This also applies to experiments in which animals have to use tools to achieve complementary feeding. These experiments also serve primarily to identify the highest mental abilities of animals.

Elements of instrumental actions appear clearly already in experiments using a bait tied to a rope; the animal can take possession of the food object only by pulling it towards itself by the rope. By complicating the situation with different combinations of ropes and varying their relative positions, it is possible to obtain valuable data not only about effectors, but also about sensory (visual and tactile) components of animal intelligence. And in this case we can talk about the method of using tools.

METHOD OF USING TOOLS

(solving problems with the help of foreign objects that must be included in the experimental situation between the animal and the target object)

Most often, experiments use simple or compound sticks, with the help of which animals (usually monkeys) can push a food object towards them or knock them down. Boxes and other objects are widely used in experiments with monkeys (especially apes), from which they must build “pyramids” to reach a high-hanging fetus. And in this case, the analysis of the structure of the animal’s objective activity in the course of solving the problem is of greatest importance.

ANALYSIS OF NON-REINFORCED MANIPULATION

WITH VARIOUS OBJECTS

Along with such more or less complex experiments, the analysis of ordinary, non-reinforced manipulation various items. Such studies make it possible to judge the effector abilities of animals, their orientation-research activities, play behavior, abilities for analysis and synthesis, etc., and also shed light on the prehistory of human labor activity.

9. SOME FEATURES OF MODERN

METHODS OF ZOO PSYCHOLOGY

Modern methods of animal psychology are aimed, first of all, at solving a certain part of the problems of animal psychology using humane, gentle methods, preserving the animal and its health.

Methods associated with non-participant observation of animals are used. In this regard, in all zoopsychological studies, photography and video recording, sound recording and other modern technical means of recording animal behavior are widely used.

Of course, technical means cannot replace the keen eye of a researcher and the living human mind, on which success in working with animals primarily depends.

In general, modern methods of animal psychology using traditional ones make it possible to comprehensively analyze the behavior of an animal, revealing its root causes.

Lecture and additional teaching materials

Introduction

The topic of our course work is “methods of zoopsychological research and research in comparative psychology.” The relevance of this topic is due to the fact that from the very beginning of the development of psychology as a science, psychologists have been interested in the problem of studying human behavior, the causes and motives of this behavior. And since man is a rather complex subject to study, many scientists have attempted to study the behavior of animals with lower development of higher mental functions. Many different attempts have been made to dissociate behavior into simpler determinants, with the help of which animal and human behavior could be further explained.

Currently, the science of animal behavior - zoopsychology - is experiencing a period of active development.

Animal psychology studies the psyche on the basis of behavior analysis: a detailed analysis of the movement of animals in the simplest situations, organized by an animal psychologist, in a scientific search based on the fact that the basis and source of mental reflection in animals is their behavior, “animal practice.” The qualitative difference between it and human practice is that animals do not rise above the level of general adaptive objective activity, while in humans, the highest, productive form of objective activity, inaccessible to animals, is of decisive importance - labor. Acquired characteristics are important for zoopsychology. It examines the process of interaction between an animal and its environment under easily controlled conditions. Knowing the past experience of the animal and placing it in a new situation, the animal psychologist studies the reflection of the environment. Currently, many different research methods in zoopsychology and comparative psychology have been created and used in practical activities. A specific psychological analysis of an animal’s behavior is carried out by an animal psychologist through a detailed study of the movements of the experimental animal in the course of solving certain problems. These tasks are set so that the movements of the animal can be used to judge the mental quality being studied with the greatest accuracy. At the same time, the physiological state of the animal, the external conditions under which the experiment is carried out, and in general all significant factors that can influence the result of the experiment must be taken into account.

Although studying the structure of an animal’s behavior primarily involves a qualitative assessment of its activity, accurate quantitative assessments in zoopsychological research are also of considerable importance. This refers to the characteristics of both the animal’s behavior and external conditions.

Object: Methods of zoopsychological research and research in comparative psychology.

Item: The process of forming the spatial orientation of animals using the labyrinth method

Goal: To identify the theoretical prerequisites for an animal’s ability to learn and develop spatial orientation.

Hypothesis: The maze method promotes learning in animals and the formation of orienting activity.

Conduct a literature analysis on the research problem.

Characterize existing approaches to studying research methods in animal psychology and comparative psychology.

Review the studies conducted by various schools of animal psychology.

Conduct analysis and interpretation of research results.

Chapter 1. Research methods in animal psychology and comparative psychology

Subject, tasks and significance of zoopsychology

Animal psychology is one of the main basic branches of general psychology that studies the manifestations of patterns and the evolution of mental reflection in animals of different levels of development. It provides important information for understanding the nature of the psyche and generalizes the general mental theory. But before we begin to consider the subject and tasks of zoopsychology, it is necessary to clarify what we mean by the psyche, behavior and mental activity of animals.

The psyche is a form of reflection that allows an animal organism to adequately orient its activity in relation to the components of the environment. At the same time, serving as an active reflection of objective reality, matter, the psyche itself is a property of highly developed organic matter. This matter is the nervous tissue of animals (or its analogues). The vast majority of animals have a brain - the central organ of neuropsychic activity.

The psyche of animals is inseparable from their behavior, by which we mean all a set of manifestations of external, mainly motor activity of an animal, aimed at establishing vital connections between the body and the environment. Mental reflection is carried out on the basis of this activity during the animal’s influence on the surrounding world. In this case, not only the components of the environment themselves are reflected, but also the animal’s own behavior, as well as the changes it makes in the environment as a result of these influences. Moreover, in higher animals (higher vertebrates), which are characterized by genuine cognitive abilities, the most complete and profound reflection of the objects of the surrounding world occurs precisely in the course of their change under the influence of the animal.

Thus, it is fair to consider the psyche as a function of the animal organism, consisting in reflecting objects and phenomena of the surrounding world in the course and result of activity directed towards this world, i.e. behavior. External activity and its reflection, behavior and psyche constitute an inextricable organic unity and can only be conditionally dissected for scientific analysis. As I.M. Sechenov showed, the psyche is born and dies with movement and behavior.

So, the root cause of mental reflection is behavior through which interaction with the environment is carried out; without behavior there is no psyche. But the opposite is also true, because, being a derivative of behavior, the psyche itself secondarily corrects and directs the external activity of the body. This is the adaptive role of the psyche: by adequately reflecting the surrounding world, the animal acquires the ability to navigate it and, as a result, adequately build its relationships with biologically significant components of the environment.

The essence of the dialectical unity of behavior and psyche is best expressed by the concept "mental activity". By the mental activity of animals we mean the entire complex of manifestations of behavior and psyche, a single process of mental reflection as a product of the external activity of the animal. Such an understanding of mental activity, the inextricable unity of the psyche and behavior of animals, opens up for zoopsychology the path to true knowledge of their mental processes and to a fruitful study of the paths and patterns of evolution of the psyche. Therefore, taking into account the primacy of behavior in mental reflection, when discussing certain aspects of the mental activity of animals, we will proceed primarily from an analysis of their motor activity in the specific conditions of their life. At the same time, the physiological state of the animal, the external conditions under which the experiment is carried out, and in general all significant factors that can influence the result of the experiment must be taken into account.

Having defined the object of zoopsychology - the mental activity of animals, we can now formulate the subject of zoopsychology as a science about the manifestations, patterns and evolution of mental reflection at the animal level, about the origin and development in the ontogeny and phylogenesis of mental processes in animals and about the prerequisites and prehistory of human consciousness. An animal psychologist studies the evolution of the psyche from its rudimentary forms to its highest manifestations, which formed the basis for the emergence of the human psyche.

Thus, the competence of a zoopsychologist lies within two facets - lower and upper, which simultaneously represent the main milestones in the evolution of the psyche in general. The lower edge marks the beginning of mental reflection, the initial stage of its development, the upper – the change of the animal psyche of the human. The lower limit means the problem of qualitative differences in reflection in plants and animals, the upper limit – in animals and people. In the first case, it is necessary to solve the issues of the origin of the psyche from a more elementary form of reflection, in the second - the origin of the human psyche from the elementary psyche of animals in relation to it.

The meaning of zoopsychology.

Data obtained in the course of zoopsychological research are important for solving fundamental problems of psychology, in particular for identifying the roots of human psychological activity, the patterns of origin and development of his consciousness. In child psychology, animal psychological research helps to identify the biological foundations of the child’s psyche, its genetic roots. Animal psychology also makes its contribution to educational psychology, because communication between children and animals has great educational and cognitive significance. As a result of such communication, complex mental contact and interaction are established between both partners, which can be effectively used for the mental and moral education of children.

In medical practice, the study of mental disorders in animals helps to study and treat nervous and mental illnesses in humans. Animal psychology data are also used in agriculture, fur farming, and hunting. Thanks to animal psychological research, it becomes possible to prepare these industries for the ever-increasing human impact on the natural environment. Thus, in fur farming, with the help of data on animal behavior, it is possible to reduce the stress of animals when kept in cages and pens, increase productivity, and compensate for various unfavorable conditions.

Animal psychology data are also necessary in anthropology, especially when solving the problem of human origins. The study of the behavior of higher primates and data on the higher mental functions of animals are extremely important for elucidating the biological prerequisites and foundations of anthropogenesis, as well as for studying the prehistory of humanity and the origins of labor activity, social life and articulate speech.

1.2 Existing approaches to studying research methods in animal psychology and comparative psychology.

As already indicated, materialistic zoopsychology proceeds in its scientific search from the fact that the basis and source of mental reflection in animals is their behavior, “animal practice.” The qualitative difference between the latter and human practice is that animals do not rise above the level of general adaptive objective activity, while In humans, the highest, productive form of objective activity, inaccessible to animals, is of decisive importance - labor. At the same time psychological analysis of specific forms of motor activity of animals, the structure of their actions, acts of their behavior, aimed at individual components of the environment, gives a clear idea of certain mental qualities and processes.

A specific psychological analysis of an animal’s behavior is carried out by an animal psychologist through a detailed study of the movements of the experimental animal in the course of solving certain problems. These tasks are set so that the movements of the animal can be used to judge the mental quality being studied with the greatest accuracy. At the same time, the physiological state of the animal, the external conditions under which the experiment is carried out, and in general all significant factors that can influence the result of the experiment must be taken into account.

An important role is played in zoopsychological research and observation of animal behavior in natural conditions. Here it is important to trace the changes that occur in the behavior of the animal during certain changes in the environment. This allows us to judge both the external causes of mental activity and the adaptive functions of the latter. Both in laboratory and field conditions, a researcher’s highly developed observational skills are the most important key to the success of his work.

Although studying the structure of an animal’s behavior primarily involves a qualitative assessment of its activity, accurate quantitative assessments are also of considerable importance in animal psychological research. This refers to the characteristics of both the behavior of the animal and external conditions (environmental parameters).

An example of a skillful combination of observation and experiment, quantitative and qualitative analysis of animal behavior can be found in the scientific work of the outstanding Soviet zoopsychologist N. N. Ladygina-Kots. So, for example, back in 1917-1919. She studied the motor skills of macaque monkeys using the "problem cage" method, that is, an experimental setup equipped with locking mechanisms that the animal had to unlock. The researchers who used this method before her were essentially only interested in the speed of solving the problem and the “ceiling” of the animal’s capabilities as the experimental situation gradually became more complex. Ladygina-Kots used the “problem cell” for a fundamentally different purpose - to understand the psyche of the monkey, to study its motor and cognitive abilities. And therefore, during the experiment, she followed not only the movement of the stopwatch hand, but primarily the movements of the experimental animal’s hands, realizing that these movements were directly related to the “mental life” of the monkey.

Already in those years, while still a young scientist, Ladygina-Kots was looking for manifestations of the psyche in the characteristics of the animal’s motor activity, in specific forms of influence on the objects around it. And in her subsequent works, she convincingly showed that an animal psychologist should study not so much what the animal does, but what How it does it. Therefore, Ladygina-Kots warned about the danger of infringing on the motor activity of the animal under study, limiting its initiative and artificially imposing certain movements, as this inevitably leads to distorted or even incorrect conclusions, and at the same time to the loss of the most valuable information about the mental qualities of the animal. In this regard, Ladygina-Kots always treated with due caution the results of studying the mental activity of animals in laboratory experimental conditions alone, clearly saw the limits of the possibilities of its application and supplemented her own experimental data with the results of observations of free, non-imposed animal behavior.

A very important point in zoopsychological research is also taking into account the biological adequacy of the experimental conditions and the methodology used. If an experiment is carried out without taking into account the specific biology of the species being studied and the natural behavior of a given animal in an experimentally simulated life situation, then the result of the study will be distorted and can easily turn out to be an artifact, as the following example shows.

Almost at the same time, in 1913-1914, two outstanding researchers of animal behavior, K. Hess and K. Frisch, studied the ability of bees to distinguish colors. Hess released the bees in a dark room, where they could fly to two light sources - different colors and different lightness. Using various combinations, the scientist found that bees always fly to a lighter source, regardless of wavelength. From this he concluded that bees do not distinguish colors.

Frisch, having structured the experiment differently, came to the exact opposite conclusion. In his experiments, bees were asked to choose colored (for example, yellow) pieces of paper in the light among white, black and gray various shades, which equalized the color intensity of reinforced colored and non-reinforced achromatic papers. The bees unerringly found yellow (or other colors) squares of paper reinforced with syrup, regardless of the lightness and saturation of their color, ignoring achromatic sheets. Thus, the ability of bees to sense color was proven.

Hess's mistake was that he conducted experiments in conditions that were biologically inadequate for bees - in the dark. Under these conditions, those forms of behavior in which color perception plays some role cannot appear, for example, when searching for food objects. Once in a dark room during the day, a bee will only look for a way out of it. At the same time, it will naturally rush to the lighter hole, regardless of the color of the light rays entering through it. Thus, the results obtained by Hess cannot indicate the presence or absence of color perception in bees and therefore cannot be used to solve the question posed.

Here the fact is clearly revealed that the reactions of animals to the same external stimuli can be very different in different life situations and functional areas. In this example, bees in one situation do not react to colors in another. Moreover, in one case (in the area of feeding behavior) bees react only to color, in another (in the area of protective behavior) only to the intensity of light, completely ignoring the color component. All this indicates the exceptional complexity of experimental zoopsychological research and the importance of creating biologically adequate conditions for conducting experiments.

1.3 Basic methods of zoopsychological research.

Specific methods of zoopsychological experimental research are very diverse, although all of them, as already mentioned, boil down to setting certain tasks for the animal. Here are just a few basic methods

The "labyrinth" method. The experimental animal is given the task of finding a path to a specific “goal” that is not directly perceived by it, which is most often food bait, but may also be a shelter (“home”) or other favorable conditions. If the animal deviates from the correct path, in some cases the animal may be punished. In its simplest form, a labyrinth looks like a T-shaped corridor or tube. In this case, when turning in one direction, the animal receives a reward, but when turning in the other, it is left without a reward or even punished. More complex mazes are made up of different combinations of T-shaped (or similar) elements and dead ends, entering which are regarded as the animal’s mistakes (Fig. 1). The results of an animal’s passage through a maze are determined, as a rule, by the speed of reaching the “goal” and by the number of mistakes made.

The “labyrinth” method makes it possible to study both issues related directly to the ability of animals to learn (to develop motor skills), and issues of spatial orientation, in particular the role of skin-muscular and other forms of sensitivity, memory, and the ability to transfer motor skills to new conditions , to the formation of sensory generalizations, etc.

Most of the above issues are also being studied the "workaround" method. In this case, the animal has to bypass one or more obstacles to achieve the “goal” (Fig. 2).

Rice. 1. Labyrinths: a) plan of the first labyrinth used in zoopsychological research (Small’s labyrinth); b) a labyrinth of “bridges”.

Unlike the “labyrinth” method, in this case the animal directly perceives the object (bait) towards which its actions are directed already at the beginning of the experiment. The speed and trajectory of movement are taken into account and assessed when searching for a workaround around an obstacle. In a slightly modified form, L.V. Krushinsky used the “workaround” method to study the ability of different animals to extrapolate. (These experiments will be described below.)

Differentiated training is aimed at identifying the ability of an experimental animal to distinguish between simultaneously or sequentially presented objects and their signs (Fig. 3). The animal’s choice of one of pairwise (or more) presented objects is rewarded (positive training); in other cases, simultaneously with the reinforcement of the correct choice, the wrong choice is punished (positive-negative training). By consistently reducing the differences between the characteristics of objects (for example, their sizes), it is possible to identify the limits of discrimination (differentiation). In this way, it is possible to obtain information characterizing, for example, the features of vision in the animal species being studied (its acuity, color perception, perception of sizes and shapes, etc.).

Rice. 2. Conducting experiments using the “workaround” method (according to Fischel)

Rice. 3. a) Yerkes apparatus for studying optical discrimination in small animals; b) an experimental device for studying color discrimination in fish; complementary food is only in a feeder of a certain color (Fischel's experiments).

The same method is used to study the processes of skill formation (in particular, to various combinations of stimuli), the memory of animals (by checking the retention of training results after a certain period of time), and the ability to generalize. In the latter case, as a rule, the dissimilarity of sequentially presented objects (figures) is gradually increased, revealing the animal’s ability to navigate by individual common features of these objects.

A variant of differential training, applicable only to higher animals, is "sample selection" method. The animal is asked to make a choice among a number of objects, guided by a sample that is shown to it directly by the experimenter or in a special apparatus. The right choice is reinforced. This method is also mainly used to study the sensory sphere of animals.

The "problem cell" (box) method. The animal is given the task of either discovering a way out of the cage by activating various devices (levers, pedals, bolts, etc.), or, conversely, entering the cage where the food is located by unlocking the locking devices. Sometimes small boxes or caskets with closures are used, the unlocking of which gives the experimental animal access to food. In a more complex experiment, all mechanisms and devices operate only in a strictly defined sequence, which must be assimilated and remembered by the animal. This method studies complex forms of learning and motor elements of the intellectual behavior of animals. It is especially convenient to use this method, naturally, for studying animals with developed grasping limbs - rats, raccoons, monkeys, etc. This also applies to setting up experiments in which animals have to use guns to achieve complementary feeding. These experiments also serve primarily for. identifying the highest mental abilities of animals.

Elements of instrumental actions are clearly evident already in experiments using a bait tied to a rope: an animal can take possession of a food object only by pulling it towards itself by the rope. By complicating the situation with different combinations of ropes and varying their relative positions, it is possible to obtain valuable data not only on the effector, but also on the sensory (visual and tactile) components of animal intelligence.

Most often, sticks (simple or compound) are used as a weapon in experiments, with the help of which animals (usually monkeys) can push or knock down a food object. Boxes and other objects are widely used in experiments with monkeys (especially apes), from which they must build “pyramids” to reach a high-hanging fetus. And in this case, the analysis of the structure of the animal’s objective activity in the course of solving the problem is of greatest importance.

Along with such more or less complex experiments, the analysis of ordinary, non-reinforced manipulation various items. Such studies make it possible to judge the effector abilities of animals, their orientation-research activities, play behavior, abilities for analysis and synthesis, etc., and also shed light on the prehistory of human labor activity.

In all animal psychological research, photography and filming, sound recording and other means of recording animal behavior are widely used. However, no technical means can replace the keen eye of a researcher and a living human mind, on which success in working with animals primarily depends.

2. Study of the method of zoopsychology and the actions performed by animals to solve various problems.

2.1 Setting up and testing experimental studies

At the beginning of the century, scientists noticed that rats learned to navigate a maze faster if they were simply placed there for 20 minutes before the learning procedure. Whether this was an accident, or whether learning was somehow influenced by previous experience, had to be tested in a special experiment, which was done by R. Blodget in 1929. For this, he took two groups of rats. One group was the control group and the other was the experimental group.

Each animal from the experimental group was placed once a day in a complex six-corridor maze for six consecutive days. The researcher recorded the time the animal traveled through the maze and the number of erroneous actions (entering a dead-end branch of the maze). At the exit, the rat was removed and received reinforcement only in a different location and after several hours had passed. Since the animals at the end of the maze did not receive reinforcement, they learned to complete the maze rather slowly. On the seventh day, the researcher placed a piece of food at the end of the maze. As a result, already on the eighth day the animals began to navigate the maze much better, and the number of errors decreased. Subsequently, the first group of animals caught up in terms of performance with the second group, which was trained to go through the maze in the same order as the first, only at the end of the maze the animals of the second group received food all the time.

L. Kardos, a Hungarian learning researcher, writes in this regard: “it is clear that the animals of the first group “changed” in some sense while running through the maze, otherwise it would be difficult to explain the subsequent learning to run faster through the maze” (Kardos L, 1988, p.141). “Change” was perceived as learning “something” that is part of normal learning, but it is hidden and its characteristics are difficult to track in learning curves (Figure 6-5). This form of learning was called latent (hidden) learning.

Let's try to imagine rats learning to navigate a maze the way E. Thorndike or any other behaviorist researcher would explain it. According to Thorndike's assumption, the animal learns to associate an event (stimulus) with an action (reaction) being implemented if the action is ultimately reinforced. In a maze, a turn in the corridor can serve as a stimulus for the animal. For each turn along the corridor of the maze, the animal develops a separate action. But the reinforcement is at the very end of the maze, so the animal associates the last turn with passage along the last corridor. The animal then learns to associate the penultimate turn with choosing and passing the correct corridor, which leads to the last corridor, and so on, until the animal reaches the entrance to the maze. It turns out that when learning to navigate a maze, an animal learns to perform a chain of reactions from the end of the maze to the beginning.

· Transfer - the influence of previously acquired individual experience on its subsequent formation.

But if a reinforcer is not placed at the end of the maze, as was done in latent learning studies with the experimental group, then why does latent learning occur? It turns out that the results with latent learning cannot be explained using learning by establishing connections between “stimuli” and “responses”.

We can also conclude that the formation of skills occurs through “trial and error”, i.e. During the learning process, the animal consolidates what is “useful” and eliminates everything else. This is well represented in experiments on laboratory rats by E. Tolman, Protopopov, I.F. Danshall.

They assumed, and later proved, that the movements produced

animals for solving problems are not chaotic, but are formed in the process of active orienting activity.

Let us consider this assumption using the example of experiments described by E. Tolman in the article “Cognitive maps in rats and humans.”

In this article, E. Tolman compares two schools of animal psychologists,

describing cognitive processes during skill development.

The first school of animal psychologists believes that the behavior of rats in a maze

comes down to the formation of the simplest connections between stimulus and response. Learning, according to this theory, consists of the relative strengthening of some connections and weakening of others; those connections that lead the animal to the right result become relatively more open for the passage of nerve impulses, and, conversely, those that lead it to dead ends are gradually blocked. It should also be noted that this school is divided into two subgroups: the first subgroup argues that the simple mechanics that take place when running a maze is that the decisive stimulus from the maze becomes the stimulus that most often matches the correct answer, compared to the stimulus , which is associated with an incorrect answer.

A second subgroup of researchers within this school argues that

The reason why appropriate connections are strengthened in comparison with others is that after the answers that are the result of correct connections, a reduction of need follows. Thus, a hungry rat in a maze tends to strive for food, and its hunger is relieved by correct answers rather than by dead ends.

belonged to myself. The idea of learning by this school is interpreted as the formation in rats of a map of the field of the environment, the so-called cognitive maps.

Let us pay attention to experiments on latent learning.

Tolman considers the best experiment conducted by Spencer and Lippitt at the University of Job. The solid line shows the error curve for I, the control group. These animals ran through the maze in the traditional way. The experiment was carried out once a day; at the end of the experiment, the rats found food in the feeder. Groups II and III were experimental. Animals of group II (dashed line) were not fed in the maze during the first six days; they received food in their cages 2 hours after the experiment. On day 7 (marked with a small cross), the rats found food at the end of the maze for the first time and continued to find it there on subsequent days. Animals of group III were treated in a similar way, with the only difference being that they first found food at the end of the maze on the 3rd day and continued to find it on subsequent days. It was observed that the experimental groups, until they found food, did not seem to learn (their error curve did not decrease). But in the days immediately following the first reinforcement, their error curve dropped strikingly. It was found that during non-reinforced trials the animals learned significantly more than they had shown before. This learning, which does not become apparent until food is introduced, is what Blodget called “latent learning.” Interpreting these results from an anthropomorphistic perspective, one could say that as long as the animals did not receive any food in the maze, they continued to waste their time walking through it and continued to reach dead ends. However, once they learned that they were going to receive food, their behavior revealed that during these previous non-reinforced trials, which included many dead ends, they had learned. They formed a "map", and later, when there was an appropriate motive, they were able to use it.

Rice. 2. Labyrinth with 6 corridors (according to Blodget, 1929)

Rice. 3. (after Blodgett, 1929)

But the best experiment demonstrating the phenomenon of latent learning was, unfortunately, not the experiment performed at Berkeley, but conducted by Spence and Lippitt at the University of Job. A simple Y-maze (Fig. 5) with two target boxes was used. Water was placed at the right end of the U labyrinth, and food was placed at the left end. During the experiment, the rats were neither hungry nor thirsty. Before each of the daily experiments, they were fed and watered. However, they wanted to run because after each run they were taken from the target box of the maze they reached and put back into a cage with other animals. They were subjected to 4 experiments per day for 7 days; 2 experiments with a feeder at the right end and 2 at the left.

Rice. 4. Error curve for groups I, II, III of rats (according to Tolman and Gonzik, (according toSpence

AndLippitou

1930)

Rice. 5. Layout of the labyrinth, 1946

In the critical experiment, the animals were divided into 2 subgroups: one of them was not fed, the other was not allowed to drink. It was found that already on the first try, the subgroup of hungry rats ran to the left end, where there was food, more often than to the right, and the subgroup of thirsty rats ran to the right end, where there was water, more often than to the left. These results show that, under conditions of previous undifferentiated and very weakly reinforced trials, the animals nevertheless learned where water was and where food was. They acquired a cognitive map, i.e., an orientation in the maze in the sense that food is at the left end and water at the right, although during the acquisition of this map they did not show any greater inclination - in the form of reactions to the stimulus - go to the end that later becomes consistent with the goal.

Thus, learning in animals is not a simple formation of a connection between stimulus and response, but is evidence of higher mental activity.

Conclusion.

Having studied the literature on this topic, we considered the theoretical approach to the study of zoopsychology (a science that studies the mental activity of animals in all its manifestations) and comparative psychology (a scientific discipline devoted to the analysis of the evolution of the psyche). Within its framework, data obtained in animal psychology, historical and ethnic psychology are integrated) and attention is concentrated on the analysis of characteristic features in the behavior of animals and humans, which contributes to the creation of many approaches to the study of these disciplines, the formation of research methods and experimental confirmation of similarities and differences in behavior.

Animal psychological experiments study the behavior of animals in solving various problems. Thus, each of the research methods considered has its own characteristics.

Basic experimental methods:

maze method(finding a path to a directly non-perceivable target object - food, shelter, etc.); workaround method(finding a path to a perceived target object bypassing one or more obstacles); simultaneous or sequential selection method(selection of objects - signals, drawings, etc. - differing in one or more, sometimes changing in a certain way, characteristics);

open field method(providing the animal with the opportunity to freely choose a path and location in a space enclosed by walls and, as necessary, complicated by structural components for opening more or less complex locking devices); method of using tools(solving problems with the help of foreign objects that should be included in the experimental situation between the animal and the target object - approaching baits with sticks or ropes, making pyramids from boxes, etc.).

This work demonstrated the significance of the hypothesis: “The maze method contributes to the learning of animals and the formation of orienting activity.”

The main findings of the study are as follows:

When studying the formation of spatial orientation of animals using the labyrinth method, we can conclude:

1) learning does not consist in the formation of “stimulus-response” connections, but in the formation of attitudes in the nervous system that act like cognitive maps;

2) such cognitive maps can be characterized as varying between narrow and broader.

Skills are formed through “trial and error”, i.e. in the learning process, the animal consolidates what is “useful” and eliminates everything else; the use of this method contributes to the learning of animals, which is not a simple formation of a connection between stimulus and response, but is evidence of higher mental activity.

The movements they make to solve problems are not chaotic, but are formed in the process of active orienting activity.

Thus, learning in animals is not a simple formation of a connection between stimulus and response, but is evidence of higher mental activity.

List of sources used

1. Fabri K.E. // Fundamentals of zoopsychology: Textbook. - M.: Publishing house. MSU, 2001.336 p.

2. Tinbergen N. // Animal behavior. M.: Mir, 1993.- 152 p.

3. Stupina S.B., Filipiechev A.O. // Animal psychology: lecture notes

4. Reader on zoopsychology and comparative psychology. – Textbook allowance for students faculty higher psychology uch. establishments. Ed. Meshkova N.N. 1998. 307 p.

5. Filippova G.G. // Animal psychology and comparative psychology

6. Kalyagina G.V. // Comparative psychology and zoopsychology. Peter, 2004. 416 p.

Zoopsychological research V.A. Wagner Influenced by Darwinian ideas in one of the important industries psychology becomes... it wouldn't be comparative psychology), Wagner denied the necessity and possibility method direct analogies with the psyche...