Presentation on the topic "biography of Anna Akhmatova." The life and work of Anna Andreevna Akhmatova Download presentation on literature biography of Akhmatova

Anna Andreevna Gorenko was born on June 11 (23), 1889 near Odessa (Bolshoi Fontan). My father was at that time a retired naval mechanical engineer. As a one-year-old child, she was transported north to Tsarskoe Selo. She lived there until she was sixteen. Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina

“...My first memories are of Tsarskoye Selo: the green, damp splendor of the parks, the pasture where my nanny took me, the hippodrome where small colorful horses galloped, the old train station and something else that was later included in the “Ode of Tsarskoye Selo.” I spent every summer near Sevastopol, on the shore of Streletskaya Bay, and there I became friends with the sea. The strongest impression of these years was the ancient Chersonesos, near which we lived...” Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina

“...I learned to read using the alphabet of Leo Tolstoy. At the age of five, listening to the teacher teaching the older children, I also began to speak French. I wrote my first poem when I was eleven years old. Poems began for me not with Pushkin and Lermontov, but with Derzhavin (“On the Birth of a Porphyritic Youth” and Nekrasov’s “Frost, Red Nose.”) My mother knew these things by heart...” Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina

“...I studied at the Tsarskoye Selo girls’ gymnasium. At first it’s bad, then much better, but always reluctantly. In 1905, my parents separated, and my mother and children went south. We lived for a whole year in Yevpatoria, where I studied at home in the penultimate class of the gymnasium, yearned for Tsarskoye Selo and wrote a great many helpless poems. The echoes of the revolution of the fifth year reached dully Evpatoria, cut off from the world. The last class took place in Kyiv, at the Fundukleevskaya gymnasium, from which she graduated in 1907. I entered the Faculty of Law of the Higher Women's Courses in Kyiv...”

I've been to Paris twice and traveled around Italy. The impressions from these trips and from meeting Amedeo Modigliani in Paris had a noticeable impact on the poetess’s work. Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina

In the spring of 1914, “The Rosary” was first published by the publishing house “Hyperborey” with a considerable circulation of 1000 copies at that time. Until 1923, there were 8 more reprints. In 1917, the third book, “The White Flock,” was published by the Hyperborey publishing house with a circulation of 2,000 copies. Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina

In August 1918, she divorced Gumilyov and married Assyriologist and poet Vladimir Shileiko. Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina After the October Revolution, Akhmatova did not leave her homeland. In the poems of these years (the collections "Plantain" and "Anno Domini MCMXXI", both 1921), grief over the fate of one's native country merges with the theme of detachment from the vanity of the world.

In the tragic years, Akhmatova shared the fate of many of her compatriots, surviving the arrest of her son, husband, the death of friends, her excommunication from literature by a party resolution in 1946 with her son Lev. Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina

Significant understatement becomes one of the artistic principles of Akhmatova’s late work. The poetics of the final work “Poem without a Hero” (), with which Akhmatova said goodbye to St. Petersburg of the 1910s, was built on it. Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina

1962 Anna Andreevna was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 1964 she became a laureate of the international Etna-Taormina Prize, and in 1965 she received an honorary degree of Doctor of Literature from Oxford University. Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina

Akhmatova died in the village of Domodedovo, March 10. After her death, in 1987, during Perestroika, the tragic and religious cycle "Requiem", written in (added), was published. Presentation by Elizaveta Dolbina

Akhmatova Anna Andreevna (real name Gorenko) was born into the family of a marine engineer, retired captain of the 2nd rank at the station. Big Fountain near Odessa. A year after her birth, the family moved to Tsarskoe Selo. Here Akhmatova became a student at the Mariinsky Gymnasium, but spent every summer near Sevastopol.

In 1905, after her parents’ divorce, Akhmatova and her mother moved to Yevpatoria. In she studied in the graduating class of the Kiev-Fundukleevskaya gymnasium, in the city at the legal department of the Kirov Higher Women's Courses.

On April 25, 1910, beyond the Dnieper in a village church, she married N.S. Gumilev, whom she met in 1903, when she was 14 and he was 17 years old. Akhmatova spent her honeymoon in Paris, then moved to St. Petersburg and from 1910 to 1916 lived mainly in Tsarskoe Selo.

Books by Anna Akhmatova The sadness that breathed in the poems of “Evening” seemed like the sadness of a wise and already weary heart and was permeated with the deadly poison of irony. “The Rosary” (1914), Akhmatova’s book, continued the lyrical plot of “Evening”. An autobiographical aura was created around the poems of both collections, united by the recognizable image of the heroine, which made it possible to see in them either a “lyrical diary” or “romantic lyrics.”

Glory After “The Rosary,” fame comes to Akhmatova. Her lyrics turned out to be close not only to schoolgirls in love, as Akhmatova ironically noted. Among her enthusiastic fans were poets who were just entering literature - M.I. Tsvetaeva, B.L. Pasternak. They reacted more restrainedly, but still approvingly, to A.A. Akhmatova. Blok and V.Ya.Bryusov. During these years, Akhmatova became a favorite model for artists and the recipient of numerous poetic dedications. Her image is gradually turning into an integral symbol of St. Petersburg poetry.

Since 1924 They stop publishing Akhmatova. In 1926, a two-volume collection of her poems was supposed to be published, but the publication did not take place, despite lengthy and persistent efforts. Only in 1940 did a small collection of 6 books see the light, and the next 2 were published in 1940.

Tragic years In the tragic years, Akhmatova shared the fate of many of her compatriots, having survived the arrest of her son, husband, friends, and her excommunication from literature by a party resolution in 1946. Time itself gave her the moral right to say, together with a hundred million people: “We have not deflected a single blow from ourselves.” Akhmatova’s creativity as the largest phenomenon of the 20th century. received worldwide recognition. In 1964, she became a laureate of the international Etna-Taormina Prize, and in 1965, she received an honorary degree of Doctor of Literature from Oxford University.

March 5, 1966 Anna Akhmatova, the Muse of artists, composers and poets, the guardian and savior of classical traditions, left this world. On March 10, after the funeral service in the St. Nicholas Naval Cathedral, her ashes were buried in a cemetery in the village of Komarovo near Leningrad. After her death, in 1987 during Perestroika, the tragic and religious cycle “Requiem” was published, written in (added)

Akhmatova

Anna Andreevna

teacher at Velsk Economic College

Arkhangelsk region

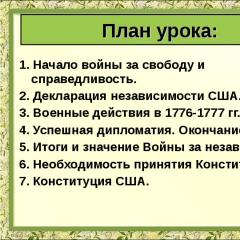

The purpose of the lesson:

-Acquaintance with the life and creative path of the famous Russian poetess of the 20th century A.A. Akhmatova

Tasks:

-compile a chronological table about the life and work of A. Akhmatova,

-prepare an answer to the question “What can you say about the poetess’s civic position throughout her life?”

Anna Andreevna Akhmatova – famous Russian poetess of the 20th century, writer, translator, critic and literary critic. Author of the famous poem “Requiem” about the repressions of the 30s.

And there are no more tearless people in the world,

arrogant and simpler than us …

A. Akhmatova

The family had four children.

She spent her childhood “near the blue sea”, she studied at the Mariinsky gymnasium in Tsarskoe Selo, at the gymnasium in the city of Evpatoria, then in Kyiv at the Fundukleevskaya gymnasium. She attended historical and literary courses for women.

Gorenko family. I.E. Gorenko, A.A. Gorenko,

Rika (in arms), Inna, Anna, Andrey.

Around 1894

Anna met Nikolai Gumilyov while still a student at the Tsarskoye Selo girls' gymnasium. Their meeting took place at one of the evenings at the gymnasium. Seeing Anna, Gumilyov was enchanted, and since then the gentle and graceful girl with dark hair became his constant muse in his work. They got married in 1910.

Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilyov and

Anna Andreevna Akhmatova

1912 - a son, Lev Gumilev, a future famous historian, was born into the family.

In the same year, the first collection of poems by A. Akhmatova was published - "Evening".

In 1914, the second collection “Rosary Beads” brought Anna Andreevna real fame.

1917 - the third book “The White Flock”, twice as large.

N.S. Gumilyov and A.A. Akhmatova with their son Lev

1925 - another collection of Akhmatova’s poems was published. After this, the NKVD for many years did not allow any work of this poetess to pass through and called it “provocative and anti-communist.”

According to historians, Stalin spoke positively about Akhmatova. However, this did not stop him from punishing the poetess after her meeting with the English philosopher and poet Berlin. Akhmatova was expelled from the Writers' Union, thereby effectively dooming her to vegetating in poverty. The talented poetess was forced to translate for many years. But she did not stop writing poetry.

Personal life.

In 1918, the poetess’s life saw a divorce from her husband, and soon a new marriage to the poet and scientist V. Shileiko.

And in 1921, following a false denunciation, Nikolai Gumilyov was shot. She separated from her second husband.

In 1922, Akhmatova began a relationship with an art critic

N. Punin.

Studying the biography of Anna Akhmatova, it is worth noting that many people close to her suffered a sad fate.

Thus, Nikolai Punin was under arrest three times, and his only son Lev spent more than 14 years in prison.

20-30s.

A. Akhmatova lives in Tsarskoe Selo - the spiritual and artistic source of all her creativity. Everything here is permeated with the spirit of Pushkin’s poetry, this gives it the strength to live.

There are so many lyres hanging on the branches here,

But there seems to be a place for mine too.

He writes articles about Pushkin, about the architectural monuments of Tsarskoe Selo, and translates. The main themes of creativity are love, the purpose of the poet.

If only you knew what kind of rubbish

Poems grow without shame,

Like a yellow dandelion by the fence,

Like burdocks and quinoa...

The inner nature of her poems has always been deeply realistic, her Muse is close to Nekrasov’s:

Give me many years of illness,

Choking, insomnia, fever,

Take away both the child and the friend,

And the mysterious gift of song -

So I pray at my liturgy

After so many tedious days,

So that a cloud over dark Russia

Became a cloud in the glory of the rays.

“I have always been with my people...” - long before “Requiem” she determined the main thing for herself - to be with her homeland on all its paths and crossroads. And she, together with her people, together with her homeland, experienced everything that befell her.

For Anna Akhmatova, poetry was an opportunity to tell people the truth. She proved herself to be a skilled psychologist, an expert on the soul.

Akhmatova’s poems about love prove her subtle understanding of all facets of a person. In her poems she showed high morality. In addition, Akhmatova’s lyrics are filled with reflections on the tragedies of the people, and not just personal experiences.

… The air of exile is bitter - Like poisoned wine.

The poem "Requiem" (1935-1940) reflects the difficult fate of a woman whose loved ones suffered from repression. When Akhmatova's son, Lev Gumilyov, was arrested, she and other mothers went to the Kresty prison. One of the women asked if she could describe THIS. After this, Akhmatova began writing "Requiem".

By the way, Punin will be arrested almost at the same time as Akhmatova’s son. But Punin will soon be released, but Lev remains in prison.

Let's try to analyze the poem!

- What facts of A. Akhmatova’s life formed the basis of the poem?

- How would you define the genre of this work?

- What can you say about the composition of the poem?

- On whose behalf is the story told?

- For what purpose do you think A. Akhmatova wrote the poem “Requiem”, what is the idea of the work?

- What visual and expressive means does the poetess use?

Let's sum it up!

Conclusions must be written down in your workbook!

Analysis of the poem "Requiem"

The poem “Requiem” by Anna Akhmatova is based on the personal tragedy of the poetess. An analysis of the work shows that it was written under the influence of what she experienced during the period when Akhmatova, standing in prison lines, tried to find out about the fate of her son Lev Gumilyov. And he was arrested three times by the authorities during the terrible years of repression.

The poem was written at different times, starting in 1935. For a long time this work was kept in A. Akhmatova’s memory; she read it only to friends. And in 1950, the poetess decided to write it down, but it was published only in 1988.

Genre - "Requiem" was conceived as a lyrical cycle, and later was called a poem.

Composition the works are complex. Consists of the following parts: “Epigraph”, “Instead of a Preface”, “Dedication”, “Introduction”, ten chapters. The individual chapters are titled: “The Judgment” (VII), “To Death” (VIII), “The Crucifixion” (X) and “Epilogue”

The poem speaks on behalf of lyrical hero . This is the poetess’s “double”, the author’s method of expressing thoughts and feelings.

The main idea of the work - an expression of the scale of the people's grief. As an epigraph, A. Akhmatova takes a quote from her own poem “So it was not in vain that we suffered together.” The words of the epigraph express the nationality of the tragedy, the involvement of each person in it. This theme continues further in the poem, but its scale reaches enormous proportions.

To create a tragic effect, Anna Akhmatova uses almost all poetic meters, different rhythms, and also a different number of feet in the lines. This personal technique of hers helps to acutely sense the events of the poem.

The author uses various trails that help make sense of people's experiences. This epithets : Rus' is “guiltless”, melancholy is “deadly”, the capital is “wild”, sweat is “mortal”, suffering is “petrified”, curls are “silver”. Lots of metaphors : “faces fall”, “weeks fly by”, “mountains bend before this grief”, “locomotive whistles sang a song of separation.” Meet and antitheses : “Who is the beast, who is the man”, “And a heart of stone fell on my still living chest.” Eat comparisons : “And the old woman howled like a wounded animal.”

The poem also contains symbols : the very image of Leningrad is an observer of grief, the image of Jesus and Magdalene is identification with the suffering of all mothers.

To leave a memory of this time, the author turns to a new symbol - a monument. The poetess asks to erect a monument near the prison wall not to her muse, but in memory of the terrible repressions of the 30s.

In 1940 The sixth collection “Out of Six Books” is published.

1941 - met the war in Leningrad. On September 28, at the insistence of doctors, she was evacuated first to Moscow, then to Chistopol, not far from Kazan, and from there through Kazan to Tashkent. A collection of her poems was published in Tashkent.

It included the poems “Courage”, “Oath”, etc.

1946 - Resolution of the Organizing Bureau of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks on the magazines “Zvezda” and “Leningrad” dated August 14, 1946, in which the work of Anna Akhmatova and Mikhail Zoshchenko was sharply criticized. Both of them were expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers.

"Alone in the dock

I’ve been sitting for almost half a century…” she wrote these days.

O.E. Mandelstam and A.A. Akhmatova

A.A.Akhmatova and B.L.Pasternak

In 1951, she was reinstated in the Writers' Union. Akhmatova's poems are published. In the mid-1960s, Anna Andreevna received a prestigious Italian prize and released a new collection, “The Running of Time.” The University of Oxford also awards a doctorate to the famous poetess.

At the end of his years, the world-famous poet and writer finally had his own home. The Leningrad Literary Fund gave her a modest wooden dacha in Komarovo. It was a tiny house that consisted of a veranda, a corridor and one room.

1966

March 5 - Anna Andreevna Akhmatova died in a sanatorium in Domodedovo (Moscow region) in the presence of doctors and nurses who came to the ward to examine her and take a cardiogram. March 7 - at 22:00 the All-Union Radio broadcast a message about the death of the outstanding poetess Anna Akhmatova.

“To live like this in freedom, Dying is like home" -

A. Akhmatova

Native land - 1961

We don’t carry them on our chests in our treasured amulet,

We don’t write poems about her sobbingly,

She doesn't wake up our bitter dreams,

Doesn't seem like the promised paradise.

We don’t do it in our souls

Subject of purchase and sale,

Sick, in poverty, speechless on her,

We don't even remember her.

Yes, for us it’s dirt on our galoshes,

Yes, for us it's a crunch in the teeth,

And we grind, knead, and crumble

Those unmixed ashes.

But we lie down in it and become it,

That’s why we call it so freely – ours.

-What can you say about A.A. Akhmatova’s civic position throughout her life?

Aphorisms by A.A. Akhmatova:

- I was in great glory, experienced the greatest infamy - and was convinced that, in essence, it was one and the same thing.

- No despair, no shame, not now, not later, not then!

- A poet’s gift cannot be taken away; he needs nothing but talent.

Slide 1

Slide 2

Slide 2

Slide 3

Slide 3

Slide 4

Slide 4

Slide 5

Slide 5

Slide 6

Slide 6

Slide 7

Slide 7

Slide 8

Slide 8

Slide 9

Slide 9

Slide 10

Slide 10

Slide 11

Slide 11

Slide 12

Slide 12

Slide 13

Slide 13

Slide 14

Slide 14

The presentation on the topic "Anna Akhmatova" can be downloaded absolutely free on our website. Subject of the project: Literature. Colorful slides and illustrations will help you engage your classmates or audience. To view the content, use the player, or if you want to download the report, click on the corresponding text under the player. The presentation contains 14 slide(s).

Presentation slides

Slide 1

Slide 2

Beginning of life...

She was born in Odessa on June 11, 1889 in the family of engineer-captain 2nd rank Andrei Antonovich Gorenko and Inna Erazmovna. After the birth of their daughter, the family moved to Tsarskoye Selo, where Anna Andreevna studied at the Mariinsky Gymnasium. She spoke French perfectly. In 1905, Inna Erasmovna divorced her husband and moved with her children, first to Evpatoria, and then to Kyiv. Here Anna Andreevna graduated from the Fundukleevskaya gymnasium and entered the law faculty of the Higher Women's Courses, still giving preference to history and literature.

Gorenko family. Anna, Inna Erasmovna, Iya,. Andrey and Victor. Kyiv. 1909

Anna's father

A. Akhmatova in childhood

Slide 3

N. Gumilev and A. Akhmatova

Anna Gorenko met her future husband, poet Nikolai Gumilev, when she was still a fourteen-year-old girl. Later, correspondence arose between them, and in 1909 Anna accepted Gumilyov’s official proposal to become his wife. On April 25, 1910, they got married in the St. Nicholas Church in the village of Nikolskaya Sloboda near Kiev. After the wedding, the newlyweds went on their honeymoon, staying in Paris all spring. In 1912, they had a son, who was given the name Lev.

Akhmatova family

Slide 4

The beginning of a creative journey...

Since the 1910s, Akhmatova’s active literary activity began. She published her first poem under the pseudonym Anna Akhmatova at the age of twenty, and in 1912 her first collection of poems, “Evening,” was published. It is much less known that when the young poetess realized her destiny, it was none other than her father Andrei Antonovich who forbade her to sign her poems with the surname Gorenko. Then Anna took the surname of her great-grandmother - the Tatar princess Akhmatova.

Slide 5

In March 1914, the second book of poems, “The Rosary,” was published, which brought Akhmatova all-Russian fame. The next collection, “The White Flock,” was released in September 1917 and was received rather restrainedly. War, famine and devastation relegated poetry to the background. But those who knew Akhmatova closely understood well the significance of her work.

Slide 6

During the revolution

Anna Andreevna broke up with N. Gumilev. In the autumn of the same year, Akhmatova married V.K. Shileiko, an Assyrian scientist and translator of cuneiform texts. The poetess did not accept the October Revolution. For, as she wrote, “everything was plundered, sold; everything was devoured by hungry melancholy.” But she did not leave Russia, rejecting the “comforting” voices calling her to a foreign land, where many of her contemporaries found themselves. Even after the Bolsheviks shot her ex-husband Nikolai Gumilev in 1921.

Slide 7

A new twist in life

December 1922 was marked by a new turn in Akhmatova’s personal life. She moved in with art critic Nikolai Punin, who later became her third husband. The beginning of the 1920s was marked by a new poetic rise for Akhmatova - the release of the poetry collections "Anno Domini" and "Plantain", which secured her fame as an outstanding Russian poetess. New poems by Akhmatova were no longer published in the mid-1920s. Her poetic voice fell silent until 1940. Hard times have come for Anna Andreevna.

Slide 8

In the early 1930s, her son Lev Gumilyov was repressed. But subsequently, Lev Gumilyov was nevertheless rehabilitated. Later, Akhmatova dedicated her great and bitter poem “Requiem” to the fate of thousands and thousands of prisoners and their unfortunate families. In the year of Stalin’s death, when the horror of repression began to recede, the poetess uttered a prophetic phrase: “Now the prisoners will return, and two Russias will look into each other’s eyes: the one that imprisoned, and the one that was imprisoned. A new era has begun.”

Slide 9

During the Patriotic War

The Patriotic War found Anna Akhmatova in Leningrad. At the end of September, already during the blockade, she first flew to Moscow, and then evacuated to Tashkent, where she lived until 1944. And suddenly everything ended. On August 14, 1946, the notorious resolution of the CPSU Central Committee “On the magazines “Zvezda” and “Leningrad” was published, in which the work of A. Akhmatova was defined as “ideologically alien.” The Union of Writers of the USSR decided to “exclude Anna Akhmatova from the Union of Soviet Writers,” thus, she was practically deprived of her livelihood. Akhmatova was forced to earn a living by translating. Akhmatova’s disgrace was lifted only in 1962, when her “Poem without a Hero” was published.

Slide 10

Confession

In the 1960s, Akhmatova finally gained worldwide recognition. Her poems have appeared in translations. In 1962, Akhmatova was awarded the International Poetry Prize "Etna-Taormina" - in connection with the 50th anniversary of her poetic activity and the publication in Italy of a collection of selected works by Akhmatova. In the same year, Oxford University decided to award Anna Andreevna Akhmatova an honorary doctorate of literature. In 1964, Akhmatova visited London, where the solemn ceremony of putting on her doctor’s robe took place. For the first time in the history of Oxford University, the British broke tradition: it was not Anna Akhmatova who ascended the marble staircase, but the rector who descended towards her. Anna Andreevna's last public performance took place at the Bolshoi Theater at a gala evening dedicated to Dante.

1 of 14

Presentation on the topic: Anna Akhmatova

Slide no. 1

Slide description:

Slide no. 2

Slide description:

The beginning of life... Born in Odessa on June 11, 1889 in the family of engineer-captain 2nd rank Andrei Antonovich Gorenko and Inna Erasmovna. After the birth of their daughter, the family moved to Tsarskoye Selo, where Anna Andreevna studied at the Mariinsky Gymnasium. She spoke French perfectly. In 1905, Inna Erasmovna divorced her husband and moved with her children, first to Evpatoria, and then to Kyiv. Here Anna Andreevna graduated from the Fundukleevskaya gymnasium and entered the law faculty of the Higher Women's Courses, still giving preference to history and literature.

Slide no. 3

Slide description:

N. Gumilev and A. Akhmatova Anna Gorenko met her future husband, poet Nikolai Gumilev, when she was still a fourteen-year-old girl. Later, correspondence arose between them, and in 1909 Anna accepted Gumilyov’s official proposal to become his wife. On April 25, 1910, they got married in the St. Nicholas Church in the village of Nikolskaya Sloboda near Kiev. After the wedding, the newlyweds went on their honeymoon, staying in Paris all spring. In 1912, they had a son, who was given the name Lev.

Slide no. 4

Slide description:

The beginning of her creative path... Since the 1910s, Akhmatova’s active literary activity began. She published her first poem under the pseudonym Anna Akhmatova at the age of twenty, and in 1912 her first collection of poems, “Evening,” was published. It is much less known that when the young poetess realized her destiny, it was none other than her father Andrei Antonovich who forbade her to sign her poems with the surname Gorenko. Then Anna took the surname of her great-grandmother - the Tatar princess Akhmatova.

Slide no. 5

Slide description:

In March 1914, the second book of poems, “The Rosary,” was published, which brought Akhmatova all-Russian fame. The next collection, “The White Flock,” was released in September 1917 and was received rather restrainedly. War, famine and devastation relegated poetry to the background. But those who knew Akhmatova closely understood well the significance of her work.

Slide no. 6

Slide description:

During the revolution, Anna Andreevna broke up with N. Gumilev. In the autumn of the same year, Akhmatova married V.K. Shileiko, an Assyrian scientist and translator of cuneiform texts. The poetess did not accept the October Revolution. For, as she wrote, “everything was plundered, sold; everything was devoured by hungry melancholy.” But she did not leave Russia, rejecting the “comforting” voices calling her to a foreign land, where many of her contemporaries found themselves. Even after the Bolsheviks shot her ex-husband Nikolai Gumilev in 1921.

Slide no. 7

Slide description:

A new turn in life December 1922 was marked by a new turn in Akhmatova’s personal life. She moved in with art critic Nikolai Punin, who later became her third husband. The beginning of the 1920s was marked by a new poetic rise for Akhmatova - the release of the poetry collections "Anno Domini" and "Plantain", which secured her fame as an outstanding Russian poetess. New poems by Akhmatova were no longer published in the mid-1920s. Her poetic voice fell silent until 1940. Hard times have come for Anna Andreevna.

Slide no. 8

Slide description:

In the early 1930s, her son Lev Gumilyov was repressed. But subsequently, Lev Gumilyov was nevertheless rehabilitated. Later, Akhmatova dedicated her great and bitter poem “Requiem” to the fate of thousands and thousands of prisoners and their unfortunate families. In the year of Stalin’s death, when the horror of repression began to recede, the poetess uttered a prophetic phrase: “Now the prisoners will return, and two Russias will look into each other’s eyes: the one that imprisoned, and the one that was imprisoned. A new era has begun.”

Slide no. 9

Slide description:

During the Patriotic War, the Patriotic War found Anna Akhmatova in Leningrad. At the end of September, already during the blockade, she first flew to Moscow, and then evacuated to Tashkent, where she lived until 1944. And suddenly everything ended. On August 14, 1946, the notorious resolution of the CPSU Central Committee “On the magazines “Zvezda” and “Leningrad” was published, in which the work of A. Akhmatova was defined as “ideologically alien.” The Union of Writers of the USSR decided to “exclude Anna Akhmatova from the Union of Soviet Writers,” thus, she was practically deprived of her livelihood. Akhmatova was forced to earn a living by translating. Akhmatova’s disgrace was lifted only in 1962, when her “Poem without a Hero” was published.

Slide no. 10

Slide description:

Recognition In the 1960s, Akhmatova finally received worldwide recognition. Her poems have appeared in translations. In 1962, Akhmatova was awarded the International Poetry Prize "Etna-Taormina" - in connection with the 50th anniversary of her poetic activity and the publication in Italy of a collection of selected works by Akhmatova. In the same year, Oxford University decided to award Anna Andreevna Akhmatova an honorary doctorate of literature. In 1964, Akhmatova visited London, where the solemn ceremony of putting on her doctor’s robe took place. For the first time in the history of Oxford University, the British broke tradition: it was not Anna Akhmatova who ascended the marble staircase, but the rector who descended towards her. Anna Andreevna's last public performance took place at the Bolshoi Theater at a gala evening dedicated to Dante.

Slide no. 11

Slide description:

End of life In the fall of 1965, Anna Andreevna suffered a fourth heart attack, and on March 5, 1966, she died in a cardiological sanatorium near Moscow. Akhmatova was buried at the Komarovskoye cemetery near Leningrad. Until the end of her life, Anna Andreevna Akhmatova remained a Poet. In her short autobiography, compiled in 1965, just before her death, she wrote: “I never stopped writing poetry. For me, they contain my connection with time, with the new life of my people. When I wrote them, I lived those rhythms, which sounded in the heroic history of my country. I am happy that I lived in these years and saw events that had no equal."

Slide no. 12

Slide description:

Slide no. 13

Slide description:

Slide no. 14

Slide description: