“Pedigree of the Buryats. find your roots! The meaning of family tree in the life of the Buryats Family tree of the Buryats

With penetration at the turn of the XVI-XVII centuries. Buddhism in Buryatia, its population received the old Mongolian script. Since that time, some of the Buryats became literate and mastered writing. Especially those young people who received their education in Datsan schools. They memorized not only prayer texts, but also became acquainted with the basics of knowledge accumulated over centuries in various parts of the world, primarily by the peoples of the East.

Along with Datsan schools, there was home education, which was practiced where local authorities and elders of the people paid appropriate attention to educating the population. In the 19th century literate people also came out of secular schools. The most capable, continuing their education, became major specialists in various fields of knowledge. Some of them mastered the folklore of their people, studied the literature and history of the Mongolian peoples. Based on the knowledge they acquired, they created works in the old Mongolian written language, primarily chronicles, historical chronicles and genealogies. Consequently, with the advent of Buddhism among the Buryats, and with it classical Mongolian writing, Buryat written literature began to develop. The first folklore, literary and historical chronicle works created in this script appeared in Buryatia in the 17th-18th centuries. Only a small part of these writings has survived to this day. One of the first works known to us is the chronicle “Balzhan-khatan tukhai durdalga” (The Story of Balzhan-khatan), written at the beginning of the 18th century. (Tsydendambaev. 1972. P. 9). In the manuscript department of the St. Petersburg branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences there is a manuscript, which, according to L.S. Puchkovsky, represents the genealogy of the Khudai family, compiled in 1773. (Puchkovsky. 1957. P. 123). In the middle of the 18th century. From the pen of the Buryat Khambo Lama Damba-Darzha Zayaev came the essay “Zamyn temdeglal” (Notes about a trip to Tibet) (Later. 1900). In 1989, under the title “The story of how the lama of the Tsongol clan, Pandit-Khambo Zayaev, went to Tibet,” it was published by S.G. Sazykin (Sazykin. 1989. pp. 121-124). Today we know several travel notes of Buryat travelers who traveled to Mongolia, Tibet, China and a number of other regions of Central and Central Asia, containing rich materials about the Mongols and the peoples of these countries, about their history and culture. These notes certainly belong to the genre of historical chronicles.

The Buryat chronicles and historical chronicles that have survived to this day mainly date back to the 19th century. and the beginning of the 20th century.

The genre of historical chronicles and chronicles was one of the most developed and popular parts of general Buryat literature in the old written classical Mongolian language, which was used by the Buryat people as a literary language until 1931. These works are original examples of literature of past centuries; they have high artistic qualities, written in beautiful style, lively, figurative language. According to G.N. Rumyantsev, among the Buryat historical works there are also those in which the artistic element and fiction, based on real historical facts, play the main role ("The Story of the Shaman Asuikhan", "The Legend of Balzhan-Khatan", etc.), and the actual historical, chronicle part is like an appendage, addition (Rumyantsev. 1960. P. 3).

These historical works were based on numerous original sources: Mongolian, Tibetan, Buryat works of various genres, historical notes, travel diaries, Datsan Buddhist books, folklore works. Chroniclers with great care and conscientiousness used authentic historical documents stored in the affairs of the offices of steppe dumas, foreign councils and datsans, in the private archives of representatives of the Buryat aristocracy, educators and learned clergy. If we consider that many archival documents of past centuries have not reached us, it becomes clear how valuable historical sources the Buryat chronicles are, therefore the information preserved in them acquires special significance. The authors of the chronicles used their own observations and recordings, heard and passed down from generation to generation of ancient traditions.

The Buryats, like other Mongolian peoples, had a developed tradition of compiling family genealogical tables and genealogies, which over time became overgrown with family legends, which, together with folk legends and information gleaned from Mongolian historical chronicles, were widely used by Buryat chroniclers as sources for writing their works. (Buryat Chronicles. 1995. P. 3).

The Buryat chronicles are for the most part similar in structure and form to Mongolian works of this genre, but at the same time differ from them in their documentation, especially starting with the events that occurred after Buryatia became part of the Russian state. Buryat chroniclers try to confirm the facts they report with references to relevant documents, indicating with great pedantry the date and number of the document.

The influence of the Mongolian chronicle tradition in a number of cases was reflected in the concept of the Buryat chroniclers in matters of the origin of the Mongols and Buryats and ancient history in general. This is especially clearly expressed in Vandan Yumsunov’s chronicle “Khoriin arban nagen esegyn ug izaguurai tuuzha” (The history of the origin of the eleven Khorin clans), the first chapter of which was written entirely under the influence of Sagan Setsen’s Mongolian chronicle “Erdeniin Erihe” (Rumyantsev. 1960. P. 13). When considering this issue, Shirab-Nimbu Khobituev used the same Mongolian chronicle, as well as the Altai Tobchi chronicle.

In addition, the authors of Buryat chronicles and historical chronicles used sources and literature in Russian, for example, “Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire”, “History of Siberia” by G. Miller, “Siberian History” by I. Fisher, etc.

In the Buryat chronicles, significant attention is paid to the life and everyday life of the Buryat-Mongolian clans and tribes, an analysis is given of the state of cattle breeding, the development of agriculture and haymaking, the introduction of new tools for the Buryats (such as scythes, sickles, plows, horse-drawn transport, etc. ), borrowed from Russian peasants. These changes in the economy contributed, according to chroniclers, to strengthening the well-being of the people. Some chronicles speak of the heavy burden of taxes and duties, the excesses of individual representatives of the tsarist local administration, embezzlement and extortion, and the oppression of the common people.

The chronicles provide ethnographic details from the life and customs of the Buryat population, a description of folk traditions and customs is given, in particular folk holidays, games, wedding ceremonies, etc. One of the cardinal problems considered in the annals and chronicles is the analysis of the position of the Buryat clans in the conditions of civil strife in the Mongol world, the advance of Russian conquerors into the Baikal region and Manchu (Qing) aggression in Central Asia.

Chronicle data tells about the history of the existence and spread of various religions, in particular about the ancient religion of the Mongol-speaking peoples - bɵɵ murgel(shamanism). Paths of penetration and spread are traced Burhanay Shazhan - Buddhist religious and philosophical teachings in the Baikal region, the homeland of the Buryat tribes. Chroniclers emphasize the close connection of Buryat history and culture with the history and culture of the general Mongolian world and the peoples of Central Asia. In a word, the Buryat chronicles examine the entire complex of political, socio-economic and cultural problems of the Buryat tribes and clans, their relationships with neighboring peoples and countries in ancient times, the Middle Ages and modern times.

Buryat historical works of past centuries (chronicles, chronicles and genealogies) are divided into Khorin, Selenga, Barguzin, Ekhirit, etc.

The most significant chronicle works are the chronicles of the Khorin Buryats, written by V. Yumsunov, T. Toboev, Sh.-N. Khobituev, also works by D.-Zh. Lombotserenov about the Selenga Buryat-Mongols and Ts. Sakharov about the Barguzin Buryats.

The chronicle “Khoriin ba Agyn Buryaaduudai Urda Sagai Tuukhe” (Past history of the Khorin and Agin Buryats) by Tugelder Toboev is one of the best in its content and style. The author begins his story with the genealogical legends of the Khori-Buryats, in particular, with the legend of Khoridoy-mergen. Then the action moves to Eastern Mongolia, where the Khorin clans find themselves dependent on the Solongut Bubei-beile Khan. The author sets out the epic tale of Balzhan-Khatan, full of dramatic events, behind which Engi(dowry) was given to the Khorin people. Further information is provided about the resettlement of the Khorin people to Transbaikalia. All these events took place even before the Russians appeared in the Baikal region. Then the author moves on to the period when the Khori-Buryats encounter new newcomers - Russian atamans who have established their dominance on the Buryat land. The author talks about the abuses, extortion and oppression inflicted by governors and atamans on the Buryat population. Much space in the chronicle is devoted to the history of the Khorin noyons, tushemils, and their merits in their careers. Information about the economy of the Khorin clans, about cattle breeding and agriculture, also about the beginning of haymaking and the establishment of economic stores, about smallpox epidemics and the beginning of smallpox vaccination is very valuable. Of great interest are the descriptions of shamanic rituals and the story of the spread of Buddhism, the appearance of the first lamas and the construction of first felt, then wooden and stone datsans. Biographical data of prominent Khorin Buddhist clergy lamas is given.

The chronicle “Khoriin arban nagen esegyn ug izaguurai tuuzha” (The history of the origin of the eleven Khorin clans), written by Vandan Yumsunov, based on the characterization of G.N. Rumyantsev, in composition, language and style, most importantly, in content, “the most brilliant work of Buryat historical literature” (Rumyantsev. 1960. P. 11). Yumsunov's work consists of 12 chapters. The chapters are divided thematically. The first chapter, dedicated to the origin of the Khori-Buryats, was written under the strong influence of the historical chronicle of Sagan Setsen. The second and third chapters provide valuable materials about the religious views of the Khorin people. The third chapter, entirely devoted to the beliefs and ritual of shamanists, still remains an unsurpassed work on the shamanism of the Transbaikal Buryats (Rumyantsev. 1960. P. 11). Of undoubted interest is the information about the life of the Buryats and their economy in the Middle Ages and modern times, collected in chapter nine. It reports data on cattle breeding, agriculture, hunting, crafts, the beginning of the use of scythes, and the difficult situation of the people as a result of natural disasters - droughts, ice; about dwellings and utensils, about the introduction of Russian harnesses, about haymaking, about the construction of pens for livestock; about raid hunting, etc.

The chronicle "Bargazhanda turushyn buryaaduud 1740 ondo buura esegyn Shabshein Ondrey turuugey Anga nyutarhaa erehen domog" (The history of the migration to Barguzin in 1740 of the Barguzin Buryats from the north under the leadership of Ondrey Shibsheev) Tsedebzhab Sakharov outlines the history of the Barguzin Buryats for about a century and a half, from 1740 to 1887 The chronicle begins with a story about how in 1740 a group of Verkholena Buryat families from the Bur clan of the Ekhirit tribe migrated to Barguzin. Ancient legends about the transition of the Verkholena Buryats to Russian citizenship, a legend about the origin of the Barguzin Taishi from the Ekhirit prince Chepchugai, about clashes between the Buryat settlers and the Tungus (Evenks) over the enclosure of lands, about the ancient inhabitants of the Barguzin region - the Barguts and Aba-Khorchins - are presented. Interesting information about the archaeological sites of Barguzin. The author of the chronicle explains the origin of the name Baikal and cites a legend about the origin of the lake itself, which is important for the study of popular views on natural phenomena (Rumyantsev. 1960. P. 9). Then the essay gives a description of the round-up hunts. The chronological account of events is brought up to 1887. The final part contains information about the administrative structure of the Barguzin Buryats, the division of the region into six clan councils, the population size, the amount of taxes and internal fees; about the way of life of the population, about religion, datsans and the Buddhist clergy.

The Selenga chronicles are divided into two subgroups according to their content. This division is due to ethnic characteristics and the history of the formation of the Selenga Buryat-Mongol clans. On a territorial basis, this concept unites clans and tribes of Buryat-Mongols of different origins, who came to the Selenga, Chikoy and Khilka valleys at different times from different places.

The first subgroup of the Selenga chronicles concerns the Buryats living in the area of the lower part of the river. Selenga, in the valleys of Orongoy, Ivolga, Ubukun, Tokhoy, Khuramshi, Sutoya. In terms of their clan composition, the inhabitants of these areas come from the Baikal region and belong to the Bulagat and Ekhirit clans that migrated to this territory in the 17th-18th centuries. These chronicles mainly reflect the history and culture of the Buryats of six clans: Alaguy, Gotol-Bumal, Baabay-Khuramsha, Abazai, Shono and Kharanuts.

The second subgroup of Selenga chronicles concerns Mongolian clans who migrated to the areas of the Dzhida, Temnik, Chikoy rivers, that is, in the territory of the present Selenga, Dzhida and Kyakhta aimaks (districts) of the Republic of Buryatia. Many of them came here from Mongolia during the campaigns of the Oirat Galdan Boshoktu Khan in Khalkha-Mongolia at the end of the 17th century. These clans formed 18 clans of Selenga Buryats. These are the Ashabagats, Atagans, Songols, Sartuls, Tabanguts, Uzons, etc. The uniqueness of the chronicles of this subgroup is that they present the history of the Buryat-Mongols in the context of mutual influence and relationships between the Mongol-speaking peoples of Central Asia. The Selenga chronicles of the second subgroup were written under the strong influence of the Mongolian chronicle tradition. At the same time, it cannot be argued that the influence of this tradition was exceptional. The authors of these chronicles were faced with the task of writing a specific history of the Buryat-Mongol clans. Therefore, relying on the Mongolian tradition and using its achievements, they created original chronicle works.

The most famous Selenga chronicles are “Selengyn Mongol-buryaaduudai tuukhe” (History of the Selenga Mongol-Buryats) by Dambi-Zhalsan Lombotserenov, “Bishykhan note” by a team of authors, “Selengyn zurgaan esegyn zone tuukhe besheg” (The history of the emergence of six Selenga clans of Buda) Budaev's toad. By the way, “Bishykhan note” is the only Buryat chronicle that presents the history of the entire Buryat people, as tribes living in Transbaikalia and Cisbaikalia.

As for the Western Buryats (Ekhirits, Bulagats, Khongodors), their chronicle tradition was poorly developed. This is partly explained by the fact that the Buddhist religion began to spread among them much later than in other parts of Buryatia, approximately from the middle of the 19th century, therefore, the old Mongolian writing came to them late, although the interest in their past among the Western Buryats was no less than among the Transbaikal ones. G.N. is right. Rumyantsev, when he writes: “Not having their own written language, the Western Buryats clothed their history in the form of oral historical traditions. Therefore, they widely have a large number of family traditions and genealogies, which were memorized by children by heart. In addition, there were attempts to write down these legends, as well as compile historical sketch of some territorial groups of Western Buryats" (Rumyantsev. 1960. P. 13). For example, the so-called Alar Chronicle is known, which gives an overview of the state of the Alar Buryats in the second half of the 19th century.

The authors of the Buryat chronicles and historical chronicles were educated representatives of the society of that time, highly respected and authoritative people, primarily representatives of the privileged classes - taishas, zaisans, noyons of various ranks, clan heads, as well as figures of the Buddhist church. With their writing and research activities, they made an important contribution to the development of literary creativity of the Buryats, to the formation and development of historical knowledge about the past and present of the Buryat and other Mongolian peoples.

Their works, historical works, together with other written monuments in the Old Mongolian script, represent an impressive body of sources on many problems of the history and culture of Buryatia, the Mongolian peoples and their connections with the peoples of Central Asia. The chronicle works created by these authors are at the same time monuments of folklore and literature, for they present Buryat-Mongolian traditions and legends, many genres of oral folk art.

For several decades, during the years of the totalitarian regime, the chronicle heritage of the Buryat-Mongol people was ignored or biasedly assessed. And many of the chronicles and chronicles that have reached us are unknown to the general population. This was explained primarily by the fact that during the years of Soviet power everything that was created in the old Mongolian script lay hidden and was forgotten. Those who tried to make this heritage public were declared pan-Mongolists or bourgeois nationalists. After the language reforms of the 30s (the Buryat language was translated into the Latin alphabet and the Tsongol dialect in 1931, into the Khorin dialect in 1936, and into the Cyrillic alphabet in 1939), the Old Mongolian (Old Buryat) written language, classified as to the attributes of pan-Mongolism, as a result the people were alienated from their centuries-old cultural heritage. The heritage, created over centuries in the old Mongolian written language, has become for the people “a book with seven seals.” The richest heritage of the past was left behind: folklore, art, chronicle and historical works.

In the current conditions, we have the opportunity to revive our historical heritage, traditional culture, and return to the people ancient artistic and historical works that have been preserved in numerous copies and copies.

The manuscripts are in various book depositories, manuscript and archival funds of many cities, in particular Ulan-Ude, Ulaanbaatar, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Chita, Tomsk. There is information about the existence of lists and copies of Buryat-Mongol chronicles in the library collections of Elista, Khukhehot, and Beijing. The collections of the repository of written monuments of the Institute of Mongolian, Buddhist and Tibetan Studies of the SB RAS contain dozens of chronicles, historical chronicles and genealogies, many of them anonymous. We see the same picture in the manuscript fund and the Archive of Orientalists of the St. Petersburg branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

It is known that they have been preserved in numerous copies and copies. Mongolian V.A. Kazakevich wrote in 1935: “Fifteen handwritten copies of the historical work of Shirab-Nimbu Khobituev are stored in the repositories of the USSR. I assume that the East Siberian archives contain a certain number of lists. Many are in private possession” (Chronicles of the Khorinskys... 1935. Issue 2 . S. 8.). Accurate information about the number of chronicles and historical chronicles created in the past, their names and authors is not yet available. Apparently there were several hundred of them.

So, painstaking work lies ahead to identify Buryat handwritten and woodcut chronicles, to establish their quantity and authorship, as well as the names and time of their writing. The most important task is the translation of chronicles and annals from the old Mongolian language, the publication of such works in the Buryat and Russian languages, and familiarization of the people with their content.

The existence of chronicles is an indicator of the fairly high culture of the Buryat-Mongol people, who in the past had developed writing and written literature. However, most of the chronicles have reached us in handwritten form. There are few woodcut publications. The question arises: why were they not printed in Datsan printing houses? After all, spiritual works in Mongolian (Old Buryat) and Tibetan languages were published there in mass editions.

The texts of the chronicles published in the old written Mongolian language and their translations in Russian have become a bibliographic rarity. Until now, most of the annals and chronicles remain unpublished, in manuscripts.

Scientists - Mongolologists and Tibetologists of Leningrad paid great attention to the study and publication of chronicles: A.I. Vostrikov, V.A. Kazakevich, N.N. Poppe, L.S. Puchkovsky, Moscow - S.D. Dylykov, N.P. Shastina, Irkutsk – Z.T. Tagarov (Dylykov. 1964; Chronicles of the Barguzinskys... 1935; Chronicles of the Khorinskys... 1935. Issue 1,2; 1940; Chronicles of Selenga... 1936; Puchkovsky. 1957; Tagarov. 1952).

The most fundamental study of Buryat chronicle works is the monograph by Ts.B. Tsydendambaeva "Buryat historical chronicles and genealogies" (Tsydendambaev. 1972). He gave an overview of more than twenty chronicles, chronicles and genealogies, and briefly discussed their content. According to these sources, he investigated the origin and composition of the Buryat people, paying attention to the language of chronicles and genealogies.

G.N. Rumyantsev devoted a number of articles to the chronicle heritage of the Buryat-Mongol people (Rumyantsev. 1949; 1960; 1965).

The publication and study of the Buryat chronicles is due to the merit of Mongolian researchers. In 1959, academician B. Rinchen, in the publication of the International Academy of Indian Culture "Shatapitaka" (Satapitaka), published, among other manuscripts, the chronicle of the Selenga Buryat-Mongols from 1887 "Selengyn Mongol-Buriadyn tobsho tuukhe" (Brief history of six administrative and eight paternal births) and the essay of Doorombo Lama Buyandalai “Buriad orondo burkhany shashny delgersen tukhay, shashny heden lamanar tukhay” (On the spread of Buddhism in Buryatia and about some lamas). B. Rinchen gave the Mongolian text in Latin transcription and an English translation. In addition, in 1965 he published chronicle data on the origin of the Hori-Buryats in the Hungarian journal Acta orientalia. In 1966, Ts. Sumyaabaatar’s book “Buriadyugiin bichgees” (From Buryat genealogies) was published in Ulaanbaatar. Professor G. Tserenkhand in the early 90s published the chronicle of Shirab-Nimbu Khobituev “Khoriin arban negan esegyn Buriad zone tuukhe” in the historical journal “Tuukhiin Sudlal”.

In 1992, for the first time in the modern Buryat literary language, a collection of Buryat chronicles “Buryadai tuukhe besheguud” (compiled by Sh.B. Chimitdorzhiev) was published, which included eleven of the largest works translated from the Old Mongolian language into the Buryat language by B. Bazarova, L. Badmaeva , D. Dorzhiev, Ts. Dugar-Nimaev, G. Ochirova, Zh. Sazhinov, R. Pubaev, G. Tudenov, Sh. Chimitdorzhiev, L. Shagdarov. The book "Buryat Chronicles" (compiled by Sh.B. Chimitdorzhiev and Ts.P. Vanchikova), published in Russian in 1995, presents nine chronicles with extensive comments, and in the second edition "Buryadai tuukhe besheguud" (compiled Sh.B. Chimitdorzhiev. 1998) - more than ten chronicles.

For the first time in the republic, an electronic information database “Peasantry of Buryatia” was created

The regular “Book Salon” that took place last week pleasantly surprised the public interested in local history, the history of their region and their family. Among the presented publications, the essentially scientific work of Alexander Pashinin, “Statistical sources on the genealogy of peasant clans (families) of the late 17th - early 20th centuries in the funds of the State Archives of the Republic of Buryatia,” aroused particular interest.

Tarbagatai district, cross on Mount Omulevka.

Suffice it to say that this work became the first systematization of genealogical archival materials in Buryatia, which was based on over 3 thousand files out of 150 thousand available in our archive. Moreover, the researcher not only brought together the sources, but also on their basis created a unique electronic information base mentioning 8.8 thousand people who lived in the republic 300-200 years ago, mainly in the current Tarbagatai and Mukhorshibir regions of Buryatia.

The database contains 605 surnames with their various variations, indicating their origin, class, religious and other characteristics. For example, the ancestors of the Kalashnikovs, Chebunins, Dumnovs, Bolonevs, Burdukovskys and many other well-known families in the republic can be found there. In a word, local historians, historians, genealogists and everyone interested in the origins of their family and clan have another unique source of information. We met with Alexander Pashinin to learn first-hand how to write a genealogy, where to start this difficult task, and how his research can be useful in all this.

Alexander Vasilyevich, four years ago, also under the auspices of the Institute of Mongolian, Buddhist and Tibetan Studies of the SB RAS, you published the book “Genealogy”, where you unvarnished the features of the origin of a number of local peasant families, to which you yourself are directly related. Surely many people would like to do the same, but I repeat once again, this is a very difficult matter. Where do you recommend starting?

My basic education is historian. Both of my parents, to whose blessed memory I dedicated my work, also graduated from the then Faculty of History and Philology of the Belarusian State Pedagogical Institute. The idea of creating a pedigree of your family, the history of your surname, was born a long time ago. My maternal roots go back to the Tarbagatai and Mukhorshibir regions. We made the final decision to compile the pedigree of our large family about seven years ago. We began to make the first samples, collect and create a common electronic photographic database of 10-12 photo albums of various families. Bit by bit, they collected and researched information about relatives with the help of the State Archive and the National Library of the Republic of Buryatia, and other archival repositories, sometimes in which they did not even expect to find something.

People often ask me the question, where to start? I see this picture in the archive all the time when, in a fit of blissful mood, a person wants to grab a ruble, but it turns out to be a penny. The most common reasons for failure are simple lack of preparation, lack of basic knowledge and lack of understanding of the very principle of search. Therefore, my first methodological recommendation would be this: first, read everything that is on this topic in libraries. The topic is the history of your region, the village where your ancestors were born, the church that was located in this village. Quite a lot of literature has been published about this in recent years. I especially recommend watching the voluminous work of Viktor Filippovich Ivanov, “Roots Going Deep,” which presents the genealogy of the residents of the village of Khasurta, Mukhorshibirsky district.

Let's assume that after reading all this the desire to study family roots has not disappeared, what should we do next?

Recently, two adult offspring approached me, who wanted to write a genealogy of their family for the anniversary of their father, who bears a very well-known surname in the republic, and were shocked that in fact they knew little about it. In such cases, most people have an irresistible desire to run to the archive, whereas the archive should be the last step in this matter. I ask the young men, do you have elderly relatives in your family, have you talked to them about this topic? No. Therefore, my second recommendation would be this - talk with all the oldest relatives who may still have a grain of information passed on to them by older ancestors, old photographs. I recommend going to the family cemetery in your village and rewriting the life dates of your great-grandparents, which will help you correlate certain events in time. And only when all these steps have been completed and you have accumulated material and an understanding of what you are actually looking for, only then can you go to the archive.

Once in the archive, the very first thing you must decide is which church needs to be “worked out”, and for this you need to know in which village-village-volost this church was located. This is important because the church in pre-revolutionary times, which is what everyone is mainly interested in, performed the duties of the current registry office. Knowing all this, the religion of your ancestors, we are looking in the archive for the so-called metric books, that is, those same church records about the birth, marriage and death of everyone who lived in a given village. Naturally, you need to start with the nearest one, from the very years when your great-grandfather and great-grandmother were born. I will say right away that registry books, being today the most widespread archival source for searching, have not been preserved for every church and not even for every year and not for every volost. Unfortunately, a huge part of the archival materials was irretrievably lost during the civil war and the first decades of Soviet power. For example, the Kyakhta Resurrection Church was consecrated for the first time in 1727, again in 1836, and the books have been preserved since 1822. The Verkhneudinsk Spasskaya Church was consecrated in 1696, restored after a fire in 1765, and the metric books survived only from 1860.

Nevertheless, in total, according to my research, today the State Archive of Buryatia contains about a thousand registry books for peasant, bourgeois, townsman, and Cossack clans. They are the most valuable source for searching for family ties, because they allow one to establish family ties on the maternal side. The fact is that they had a separate column where the names of the child’s godparents were entered. Since in those days the closest relatives of the mother and father often became godparents (in the event of the death of the parents, they most often took the child to be raised), then by the patronymics and surnames of these people it is possible to determine the mother’s maiden name, the first and last name of her father and other close relatives on the maternal side. For example, when compiling my own pedigree, I had to “work through” the same registry books three times, because each time there were more and more new relatives.

As a person who himself was researching his ancestry and was faced with the fact that the metrical books for our church have not been preserved, I ask, what to do in this case?

In fact, many other materials have been preserved on church, administrative, police and military mobilization records, which also contain a lot of information on this topic. We are talking primarily about revision tales (then the All-Russian population census was called that), family and recruitment lists, confessional lists, salary and capitation books, and so on.

- Which regions of the republic have the most historical documents preserved?

The Tarbagatai, Kabansky, and Pribaikalsky districts were most fortunate in this regard. According to Tarbagatai, in particular, in the 20s, thanks to the efforts of archivists and enthusiasts of their work, and somewhere and their personal feat, all the files were transported on carts to the Verkhneudinsk archive. The former Bichursky and Bolshekunaleysky volosts were completely unlucky in this regard, because in 1921-1922 the archive there was almost completely destroyed. The archive in Kyakhta was very badly damaged; very little remains in the Dzhidinsky district. But I can say that some of the materials, for example, on the Bichursky, Kyakhtinsky, Dzhidinsky districts, are today in Chita, in the State Archive of the Trans-Baikal Territory.

My job was to analyze and systematize the surviving sources on the subject of genealogy, establishing the kinship of people of various nationalities - Russians, Buryats, Ukrainians, Jews, Evenks. Among other things, the electronic database created as part of this study makes it possible, for example, to presumably determine the founders of some villages by the names of the first inhabitants of Western Transbaikalia. Thus, the founder of the village of Burnashevo in the Tarbagatai region in 1747 could have been a parishioner of the Zosimo-Savvatievskaya Church Ivan Burnashev, the village of Kharitonovo - in 1693, the Selenga mounted Cossack Stefan Kharitonov. Using the database, for example, you can also trace how the original versions of some surnames changed - Vilmov in 1744 turned into Vilimov by 1811, Yamanakov in 1750 - into Yemanakova in 1751, and so on.

Your information database of 605 names of peasant families is declared to be electronic, but where can I find it?

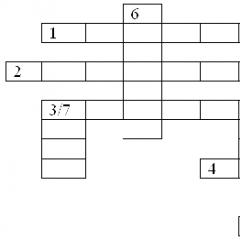

The database is planned to be placed in the State Archives of the Republic of Buryatia for free use, including for the purpose of restoring the genealogies of peasant clans (families) in Western Transbaikalia, both in descending and ascending lines. It is possible to compile and reconstruct genealogical tables, paintings, trees, family cards and dossiers. It is planned that it will be replenished through the further accumulation of archival material in it as a result of the study of other sources of the 18-19 centuries.

- Thanks for the interesting information!

DIV_ADBLOCK358">

From time immemorial, people have had it, and this is in their nature: the elders care for the younger, preserving the memory of their good deeds and ancestors. In ancient times, when there was no written language yet, the Mongols and Buryats jealously guarded their memory; from generation to generation they told their children about their ancestry, which was a kind of oral “memoir” translated from Latin as “memory”, “recollection”.

It is historically recognized in the world that the Mongols and Mongol-speaking peoples sacredly preserve names from the older generation, our storytellers - and many others knew their ancestors perfectly well until the 18th-20th generation, what happened 5-6-7 centuries ago. The Persian scientist and historian Rashid ad-din wrote at the beginning of the 14th century: “... the custom of the Mongols is such that they preserve the genealogy of their ancestors and teach and instruct in the knowledge of the genealogy of every child born. The Mongols all have a clear and distinct family tree that none of the other tribes, excluding the Mongols, have this custom.”

2. My family

My grandfather is Fedor Nikolaevich Konyaev, he is 84 years old today. Born in Khokhorsk, studied, worked as a tractor driver, foreman, and chairman of the Village Council for two convocations. Knight of the Order of the Red Banner of Labor for growing a high wheat harvest in 1967, Winner of Socialist Labor, was repeatedly awarded certificates for achievements and best labor performance. He leads an active lifestyle, does housework: milks a cow, raises several pigs per year. He constantly goes fishing, hunting, to Baikal, to the Angara. In his free time, he reads newspapers, books, watches many TV shows, plays chess and cards. Has no bad habits. He still drives his own car.

My grandmother’s name was Anisya Nikolaevna Konyaeva, nee Asalkhanova, born in the village of Khokhorsk, she and her grandfather lived for 52 years, gave birth to and raised five children.

My great-grandfather's name was Misyulkha Konyaev, he had 13 children, only five survived - my grandfather Fedor and his brothers: Ion, Ivan, Sergei, sister Fedosya. Buryats used to give their children names in honor of someone. This tradition is observed in our family: I am named after my grandfather, my father Sergei is named after my grandfather’s brother, my brother Nikolai is named after his great-grandfather Misyulkha, translated into Russian means Nikolai. Engelsina was named after her maternal grandmother. The second sister was named after his wife, uncle, and expert on our genealogy, Georgy Egorovich Konyaev - Sozha.

My great-grandfather Misyulkha Konyaev’s father Erme, who worked for Taisha Innokenty Pirozhkov as a freight forwarder, carried grain to various fairs and sales, managed horses well, rode fast, they say they had the fastest horses in the ulus, that’s why my ancestors were given the surname Konyaev, and our Buryat surname is Khuyaataan. The version about the Konyaev surname was told by my father’s aunt Fedosya Nikolaevna Balkhanova (she has a higher education as a teacher of her native language and literature). Khuyaa was the great-grandson of Khokhor, the founder of our village of Khokhorsk. Khokhor's real name was Darhi, according to legend (according to) he was blind in one eye, which he damaged during the round-up hunt “Zegete aba”. (Recorded from the words of my aunt Konyaeva TF, October 3, 2010).

3. My ancestry

Fedor Konyaev

11th grade Khokhor secondary school

Bokhansky district.

Within the walls of the archive, many people learn for the first time about the high position in society, military merits and talents of their relatives.

Just as a tree cannot live without roots, so the human future is unthinkable without the past, says Butit Zhalsanova, director of the State Archive of Buryatia.

If a person does not know his roots, it is unknown what information about his family he will pass on to his descendants, she says. - Every person should have a story that lasts from time immemorial, and not counted in one “today.” I think everyone would be interested to know what abilities his ancestors had that might be passed on to their children. In addition, there are many cases when, not knowing their roots, people marry their relatives - second cousins. But the Buryats used to have a taboo on unions between relatives up to the seventh generation. To avoid this, young people should know the history of their family.

Requirements of shamans and simple curiosity

In the State Archives of the Republic, a descending method of establishing pedigree is more often used, that is, from oneself to one’s ancestors. The most important thing, archivists say, is to know what family your ancestors belonged to, or at least the area where they lived. Any information will be useful, including family legends.

For example, I belong to the small Sagan clan of Khorin Buryats,” explains Butit Zhalsanova. - My ancestors, at the beginning of the 19th century, migrated from the Tugnui valley to the Agin steppes under the leadership of Mukhu Unaganov, the well-known zaisan of the Sagan family. He was sent there to raise the standard of living of the Agin Buryats. This is how my ancestors ended up in Aga. Our family already has a written pedigree. But one day I wondered whether it really coincided with the Reviz tales. And I was pleasantly surprised by the complete coincidence.

Butit Zhalsanova looks at the family list of the Aginsk Steppe Duma for 1893 for the Mogoytuevskaya foreign council. “My ancestors were part of this council. On the left side there is a revision of men, on the right - women. It also indicates which family had how many livestock,” she says.

Today, many people explain the search for their ancestry through shamanic rituals, which often require knowing the name of a particular ancestor. Others search simply out of interest. Many Russians, Old Believers, Poles, Evenks and Jews also come here to learn the history of the family.

Previously, it was not customary to talk about this, but now many are looking for their ancestors who were leaders of local government: these are the headman, the head of the council, the taisha of the Steppe Duma, assessors and others. And they are proud if they find it,” the archive director names another reason.

Where does the study of genealogy begin?

Few people know their ancestors beyond their great-grandmothers, says Tatyana Lumbunova, head of reading room No. 1 of the State Archives of Buryatia. According to her, unprecedented interest in this topic has arisen in recent years.

The increased popularity can probably be explained by the revival of national self-awareness among the Buryats. In the visitor book last year, we recorded about a thousand people who came just for this.

Mostly, the reading room of the archive is occupied by researchers: scientists, graduate students, graduate students. People come here from all over Buryatia, from the Irkutsk region, the Trans-Baikal Territory - from all over Russia and even from other countries - to find family trees.

Residents of our republic often study on their own,” says Tatyana Lumbunova. - From other regions they send requests by e-mail to the information desk, by regular mail, or come themselves. Usually, seekers know only the names of their grandparents, and less often their great-grandparents. We ask, first of all, to properly interview elderly relatives, which of them remembers their ancestors on the maternal and paternal lines. Then you should contact the regional registry offices - at the place of birth, marriage and death of relatives.

It is better to start working with the ancestors closest to you - for example, with grandparents, and then go deeper and deeper.

Parish registers of churches and documents of the Steppe Dumas

The archives of the republic have a documentary base up to 1917. The Russian Orthodox population usually studies their genealogies using the metric books of churches. Most of the books have already been digitized, and five computers are installed in the reading room, which greatly facilitates the work.

Among the Buryats, if they are baptized Orthodox, you can also search in the metric books of churches, but more often - in the documents of the Steppe Dumas, says Tatyana Lumbunova. - They contain Revision tales with nominal lists by gender. That's why we ask what kind of person you are. Many people do not know this, and we are trying to find out the genus based on the locality in which the person’s ancestor lived.

The difficulty of searching among the Buryats is usually due to the difficulty of reading documents from the 19th century.

People often turn to me for a hint on how to read this or that word, make out first and last names, etc.,” says the archivist. - If this is a Russian text, I advise you to use the Old Church Slavonic alphabet. As for the eastern Buryats, documents are mainly in Mongolian writing - these are the Kyakhtinsky, Selenginsky, Khorinsky, Mukhorshibirsky, Eravninsky districts. The problem of translation often arises - the State Archives does not have its own translator on staff. There is still a lot of work ahead to translate these documents into Russian and Buryat languages. We suggest that many come immediately with an interpreter, who can be found at the BSC or at the Oriental Faculty of BSU, at the Mongolian department.

For the Irkutsk region, the archive contains many household and family lists in Russian - they are easier to research.

If you want to find an ancestor who died during the war, you can refer to the websites “Memorial”, “Feat of the People 1941 - 1945” and the website of the Central Archive of the Russian Ministry of Defense.

“Among the ancestors there were people whom I did not even expect to find”

Alexander Pashinin, Ph.D., researcher on sources on the genealogy of peasant clans (families) of the pre-revolutionary period in the funds of the State Archive of Buryatia:

I dedicated my first monograph to my genealogy. In 2011, I entered the archive for the first time and to this day I regularly visit it for the purpose of research. It took about a year and a half to restore my ancestry. Among the ancestors there were people whom I did not even expect to find. For example, Gavrila Lovtsov, a Pentecostal and one of the founders of Verkhneudinsk, arrived here in 1665. Many relatives were found among state peasants, townspeople, commoners, settled baptized foreigners, and on exile expeditions. Unfortunately, our sources have certain limitations: for example, we have the fourth Revision tale of 1782 about the inhabitants of Buryatia, but we do not have the 1st, 2nd and 3rd. They are in the Russian State Archive of Ancient Acts (RGADA) in Moscow.

“If you dig around, you can find everything”

Leonty Krasovsky, head of the department of the Republican Committee of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation for work with youth:

- Most young people today do not bother with the topic of pedigree. They think that it is impossible to restore it. But if you dig around, you can find everything. And the closer you are to the truth, the more inspired you become. I painted my family tree up to the 11th generation - up to Bulagat. The idea appeared about a year and a half ago, I talked with older relatives and searched on the Internet. Recently, my sister sent me her mother's significant work, and the whole picture became clear. My family is Ongoy. When one day a shaman asked me what kind of family I was and found out that I was Ongoy, he said that I needed to pray twice as much, because there were strong shamans in my family. Now I am searching for information about how and what my ancestors lived and what they did. Don't be lazy and look for your ancestors!

- Most young people today do not bother with the topic of pedigree. They think that it is impossible to restore it. But if you dig around, you can find everything. And the closer you are to the truth, the more inspired you become. I painted my family tree up to the 11th generation - up to Bulagat. The idea appeared about a year and a half ago, I talked with older relatives and searched on the Internet. Recently, my sister sent me her mother's significant work, and the whole picture became clear. My family is Ongoy. When one day a shaman asked me what kind of family I was and found out that I was Ongoy, he said that I needed to pray twice as much, because there were strong shamans in my family. Now I am searching for information about how and what my ancestors lived and what they did. Don't be lazy and look for your ancestors!

Leonty was able to paint his family tree up to the 11th generation

The reading room of the State Archive of Buryatia is open from Monday to Thursday. Friday is a sanitary day.

Address: Ulan-Ude, st. Sukhbaatar, 9a (entrance to the courtyard through the building of the People's Khural of Buryatia using a passport).

Friday, February 07

13th lunar day with the element Fire. Auspicious day for people born in the year of the Horse, Sheep, Monkey and Chicken. Today is a good day to lay the foundation, build a house, dig the ground, start treatment, buy medicinal preparations, herbs, and conduct matchmaking. Going on the road means increasing your well-being. Unfavorable day for people born in the year of the Tiger and Rabbit. It is not recommended to make new acquaintances, make friends, start teaching, get a job, hire a nurse, workers, or buy livestock. Hair cutting- to happiness and success.

Saturday, February 08

14th lunar day with the element Earth. Auspicious day for people born in the year of the Cow, Tiger and Rabbit. Today is a good day to ask for advice, avoid dangerous situations, perform rituals to improve life and wealth, move to a new position, buy livestock. Unfavorable day for people born in the year of the Mouse and Pig. It is not recommended to write essays, publish works on scientific activities, listen to teachings, lectures, start a planned business, get or help get a job, or hire workers. Going on the road means big troubles, as well as separation from loved ones. Hair cutting- to increase wealth and livestock.

Sunday, February 09

15th lunar day with the element Iron. Benevolent deeds and sinful acts committed on this day will multiply a hundred times. A favorable day for people born in the year of the Dragon. Today you can build a dugan, suburgan, lay the foundation of a house, build a house, start a planned business, study and comprehend science, open a bank account, sew and cut clothes, as well as for tough decisions on some issues. Not recommended move, change place of residence and work, bring a daughter-in-law, give a daughter as a bride, and also hold a funeral and wake. Hitting the road means bad news. Hair cutting- to good luck, to favorable consequences.