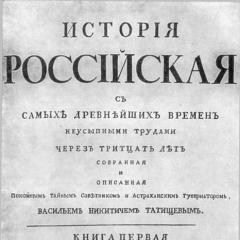

Sparta summary. Sparta: political and social system. Laconian Valley and modern Sparta

The country that will be discussed in the article was called Lacedaemon, and its warriors could always be recognized by the Greek letter λ (lambda) on their shields.

But following the Romans, we all now call this state Sparta.

If you believe Homer, Sparta goes back to ancient times, and even the Trojan War began due to the abduction of the Spartan queen Helen by Prince Paris. But the events that could become the basis of the Iliad, the Lesser Iliad, the Cyprians, the poems of Stesichorus and some other works are dated by most modern historians to the 13th-12th centuries. BC. And Sparta, known to everyone, was founded no earlier than the 9th-8th centuries. BC. Thus, the plot of the abduction of Helen the Beautiful is apparently an echo of the pre-Spartan legends of the peoples of the Cretan-Mycenaean culture.

At the time of the appearance of the Dorian conquerors on the territory of Hellas, the Achaeans lived on these lands. The ancestors of the Spartans are considered to be people of three Dorian tribes - Dimani, Pamphili, and Gilleans. It is believed that they were the most warlike of the Dorians, and therefore advanced the furthest. But perhaps this was the last “wave” of Dorian settlement and all other areas had already been captured by other tribes. The defeated Achaeans, for the most part, were turned into state serfs - helots (probably from the root hel - to captivate). Those of them that managed to retreat to the mountains were also conquered after some time, but received a higher status as perieks (“living around”). Unlike the helots, the perieks were free people, but their rights were limited; they could not take part in public meetings and in governing the country. It is believed that the number of Spartans themselves never exceeded 20–30 thousand people, of which 3 to 5 thousand were men. All capable men were part of the army; military education began at the age of 7 and lasted until the age of 20. There were 40–60 thousand perieks, and about 200 thousand helots. There is nothing supernatural for Ancient Greece in these figures. In all states of Hellas, the number of slaves greatly exceeded the number of free citizens. Athenaeus in the “Feast of the Wise Men” reports that, according to the census of Demetrius of Phaleres, in “democratic” Athens there were 20 thousand citizens, 10 thousand metecs (non-full-fledged inhabitants of Attica - settlers or freed slaves) and 400 thousand slaves - this is quite consistent with the calculations of many historians . In Corinth, according to the same source, there were 460 thousand slaves.

The territory of the Spartan state was a fertile valley of the Eurotas River between the Parnon and Taygetos mountain ranges. But Lakonica also had a significant drawback - the coast was inconvenient for navigation, which is perhaps why the Spartiates, unlike the inhabitants of many other Greek states, did not become skilled sailors and did not establish colonies on the coast of the Mediterranean and Black Seas.

Map of Hellas

Archaeological finds suggest that in the Archaic era the population of the Spartan region was more diverse than in other states of Hellas. Among the inhabitants of Laconia at that time there were three types of people: “flat-faced” with wide cheekbones, with faces of the Assyrian type and (to a lesser extent) with faces of the Semitic type. In the first images of warriors and heroes one can most often see “Assyrians” and “flat-faced”. In the classical period of Greek history, the Spartans are depicted as people with a moderately flat face type and a moderately protruding nose.

The name “Sparta” is most often associated with the ancient Greek word meaning “human race”, or close to it - “sons of the earth”. Which is not surprising: many peoples call their fellow tribesmen “people”. For example, the self-name of the Germans (Alemans) means “all people.” Estonians previously called themselves “the people of the earth.” The ethnonyms “Magyar” and “Mansi” originate from one word meaning “people”. And the self-name of the Chukchi (luoravetlan) actually means “real people.” There is an ancient proverb in Norway, which literally translated into Russian sounds like this: “I love people and foreigners.” That is, foreigners are politely denied the right to be called people.

It should be said that in addition to the Spartans, Spartans also lived in Hellas, and the Greeks never confused them. Sparta means “scattered”: the origin of the word is associated with the legend of the abduction by Zeus of the daughter of the Phoenician king Agenor, Europa, after which Cadmus (the name means “ancient” or “eastern”) and his brothers were sent by their father in search, but “scattered” around the world without ever finding her. According to legend, Cadmus founded Thebes, but then, according to one version, he and his wife were expelled to Illyria, according to another - they were turned by the gods first into snakes, and then into the mountains of Illyria. Cadmus's daughter Ino was killed by Hera because she nursed Dionysus, and her son Actaeon died after killing the sacred doe Artemis. The famous Theban commander Epaminondas came from the Spartan family.

Not everyone knows that initially it was not Athens, but Sparta that was the generally recognized cultural center of Hellas - and this period lasted for several hundred years. But then in Sparta the construction of stone palaces and temples suddenly stopped, ceramics became simpler, and trade withered away. And the main business of the citizens of Sparta becomes war. Historians believe that the reason for this metamorphosis was the confrontation between Sparta and Messenia, a state whose area was then larger than that of Lacedaemon, and which significantly exceeded it in population. It is believed that the most irreconcilably minded representatives of the old Achaean nobility, who did not accept defeat and dreamed of revenge, found refuge in this country. After two difficult wars with Messenia (743-724 BC and 685-668 BC), “classical” Sparta was formed. The state turned into a military camp, the elite practically abandoned their privileges, and all able-bodied citizens became warriors. The Second Messenian War was especially terrible; Arcadia and Argos took the side of Messenia, at some point Sparta was on the verge of a military disaster. The morale of its citizens was undermined, men began to shirk the war - they were immediately enslaved. It was then that the Spartan custom of cryptia appeared - the night hunt of young men for helots. Of course, the respectable helots, on whose work the well-being of Sparta was based, had nothing to fear. Let us recall that the helots in Sparta belonged to the state, but at the same time they were assigned to those citizens whose land they farmed. It is unlikely that any of the Spartiates would be happy with the news that his serfs were killed at night by teenagers who broke into their house, and he now had problems with contributions to the syssitia (with all the ensuing consequences, but more on that later). And what is the valor of such night attacks on sleeping people? Everything was wrong. At that time, detachments of Spartan youths went out on night “watches” and caught on the roads those helots who intended to flee to Messenia or wanted to join the rebels. Later this custom turned into a war game. In peacetime, helots were rarely seen on night roads. But if they did come across them, they were a priori considered guilty: the Spartans believed that at night serfs should not wander along the roads, but sleep in their beds. And if the helot left his house at night, it means he was planning treason or some kind of crime.

In the Second Messenian War, victory for the Spartans was brought by a new military formation - the famous phalanx, which dominated the battlefields for many centuries, literally sweeping away opponents in its path.

Soon the enemies figured out to place lightly armed peltasts in front of their formation, who fired at the slowly marching phalanx with short spears: the shield with a heavy dart stuck into it had to be thrown, and some of the soldiers turned out to be vulnerable. The Spartans had to think about protecting the phalanx: the peltasts began to be dispersed by young, lightly armed warriors, often recruited from the Periek mountaineers.

Phalanx with guard

After the formal end of the Second Messenian War, the partisan war continued for some time: the rebels, who fortified themselves on Mount Ira, bordering Arcadia, laid down their arms only 11 years later - according to an agreement with Lacedaemon, they left for Arcadia. The Messenians who remained on their land were turned into helots: according to Pausanias, under the terms of the peace treaty they had to give half of the harvest to Lacedaemon.

So, Sparta got the opportunity to use the resources of the conquered Messenia. But there was another very important consequence of this victory: a cult of heroes and a ritual of honoring warriors appeared in Sparta. Subsequently, Sparta moved from the cult of heroes to the cult of military service, in which conscientious fulfillment of duty and unquestioning obedience to the orders of the commander were valued above personal exploits. The famous Spartan poet Tyrtaeus (a participant in the Second Messenian War) wrote that a warrior’s duty is to stand shoulder to shoulder with his comrades and not try to show personal heroism to the detriment of the battle order. In general, don’t pay attention to what’s happening to your left or right, stay in line, don’t retreat and don’t push forward without orders.

The famous diarchy of Sparta - the rule of two kings (archagetes) - was traditionally associated with the cult of the twin Dioscuri. According to the most famous and popular version, the first kings were the twins Proclus and Eurysthenes - the sons of Aristodemus, a descendant of Hercules, who died during a campaign in the Peloponnese. They allegedly became the ancestors of the Euripontid and Agid (Agiad) clans. However, the co-king kings were not relatives; moreover, they originated from hostile clans, as a result of which a unique ritual of monthly mutual oath of kings and ephors even appeared. The Euripontids, as a rule, sympathized with Persia, while the Agiads led the anti-Persian “party.” The royal dynasties did not enter into marriage alliances with each other; they lived in different regions of Sparta, each of them had their own sanctuaries and burial places. And one of the kings was descended from the Achaeans!

Part of the power was returned to the Achaeans and their kings by Lycurgus, who was able to convince the Spartans that the deities of the two tribes would be reconciled if royal power was divided. At his insistence, the Dorians had the right to organize holidays in honor of the conquest of Laconia no more than once every 8 years. The Achaean origin of the Agiads has been repeatedly confirmed in various sources and is beyond doubt. King Cleomenes I in 510 BC said to the priestess of Athena, who did not want to let him into the temple on the grounds that Dorian men were forbidden to enter it:

"Woman! I am not a Dorian, but an Achaean!"

The already mentioned poet Tyrtaeus spoke of the full-fledged Spartans as aliens who worshiped Apollo and came to the Heraclidean city, which had become their home:

“Zeus gave the Heraclides a city that is now our home.

With them, leaving Erineus in the distance, blown by the wind,

We have come to a wide expanse in the land of Pelops.

Thus, from the magnificent temple, Apollo the Far-Rider spoke to us,

Our golden-haired god, king with a silver bow.”

The patron god of the Achaeans was Hercules, the Dorians revered Apollo more than all the gods (translated into Russian this name means “Destroyer”), the descendants of the Mycenaeans worshiped Artemis Orthia (more precisely, the goddess Orthia, later identified with Artemis).

Memorial plaque from the Temple of Artemis Orthia in Sparta

The laws of Sparta (the Sacred Treaty - Retra) were consecrated in the name of Apollo of Delphi, and ancient customs (rhythma) were written down in the Achaean dialect.

For the already mentioned Cleomenes, Apollo was a foreign god, therefore, one day he allowed himself to falsify the Delphic oracle (in order to discredit his rival, Demaratus, a king from the Eurypontid family). For the Dorians, this was a terrible crime; as a result, Cleomenes was forced to flee to Arcadia, where he found support, and also began preparing an uprising of the helots in Messenia. The frightened ephors persuaded him to return to Sparta, where he met his death - according to the official version, he committed suicide. But Cleomenes treated the Achaean cult of Hera with great respect: when the Argive priests began to prevent him from making a sacrifice in the temple of the goddess (and the Spartan king also performed priestly functions), he ordered his subordinates to drive them away from the altar and flog them.

The famous king Leonidas, who stood in the way of the Persians at Thermopylae, was Agiad, that is, an Achaean. He brought with him only 300 Spartiates (probably this was his personal detachment of hippean bodyguards, which was assigned to every king - contrary to the name, these warriors fought on foot) and several hundred perieki (Leonid also had troops of Greek allies at his disposal, but more on this will be described in the second part). But the Dorians of Sparta did not go on a campaign: at that time they celebrated the sacred holiday of Apollo of Carnea and could not interrupt it.

Monument to King Leonidas in modern Sparta, photo

Gerusia (Council of Elders, consisting of 30 people - 2 kings and 28 geronts - Spartiates who reached the age of 60, elected for life) was controlled by the Dorians. The People's Assembly of Sparta (Apella, Spartiates 30 years of age and older had the right to participate in it) did not play a big role in the life of the state: it merely approved or rejected proposals prepared by Gerusia, and the majority was determined “by eye” - whoever shouts loudest gets the Truth. The true power in Sparta of the classical period belonged to five annually elected ephors, who had the right to immediately punish any citizen who violated the customs of Sparta, but were not subject to anyone's jurisdiction. The ephors had the right to judge kings, controlled the distribution of military spoils, the collection of taxes and military recruitment. They could also expel from Sparta foreigners who seemed suspicious to them and supervised the helots and perieci. The ephors did not even spare the hero of the Battle of Plataea, Pausanias, who they suspected of trying to become a tyrant. The regent of the son of the famous Leonidas, who tried to hide from them at the altar of Athena Copperhouse, was walled up in the temple and died of hunger. The ephors constantly suspected (and sometimes with good reason) the Achaean kings of flirting with the helots and perieks and feared a coup d'etat. The king from the Agid family was always accompanied by two ephors during the campaign. But exceptions were sometimes made for the Euripontid kings; only one ephor could accompany them. The control of the ephors and gerousia over all affairs in Sparta gradually became truly total: the kings were left only with the functions of priests and military leaders, but at the same time they were deprived of the right to independently declare war and make peace, and even the route of the upcoming campaign was certified by the Council of Elders. The kings, who seemed to be revered as people closest to the gods, were always suspected of treason and even bribes, allegedly received from the enemies of Sparta, and the trial of the king was commonplace. In the end, the kings were practically deprived of their priestly functions: in order to achieve greater objectivity, ministers of worship began to be invited from other states of Hellas. Decisions on vital issues continued to be made only after receiving the Delphic oracle.

Delphi, modern photography

The vast majority of our contemporaries are confident that Sparta was a totalitarian state, the social structure of which is sometimes called “war communism.” The Spartiates are considered by many to be invincible “iron” warriors who had no equal, but at the same time they are stupid and limited people who spoke in monosyllabic phrases and spent all their time in military exercises. In general, if you discard the romantic aura, you will get something like the Lyubertsy Gopniks of the late 80s - early 90s of the twentieth century. But should we, Russians, walking the streets with a bear in our arms, a bottle of vodka in our pocket and a balalaika at the ready, be surprised at the black PR and believe the Greeks of the policies hostile to Sparta? We, after all, are not the scandalously famous Briton Boris Johnson (former mayor of London and former foreign minister), who just recently, having suddenly read Thucydides in his old age (truly, “not a horse’s feed”), compared ancient Sparta with modern Russia, and Great Britain and the USA, of course, with Athens. It’s a pity that I haven’t read Herodotus yet. He would have especially liked the story of how the progressive Athenians threw Darius's ambassadors off a cliff - and, as befits true beacons of freedom and democracy, proudly refused to apologize for this crime. Not like the stupid totalitarian Spartans, who, having drowned the Persian ambassadors in a well (“earth and water” suggested searching in it), considered it fair to send two high-ranking volunteers to Darius - so that the king would have the opportunity to do the same with them. And it’s not like the Persian barbarian Darius, who, you see, did not want to drown, hang, or quarter the Spartiates who came to him - a wild and ignorant Asian, you can’t call it anything else.

However, the Athenians, Thebans, Corinthians and other ancient Hellenes, of course, differ from Boris Johnson, since, according to the same Spartans, they still knew how to be fair - once every four years, but they knew how. Nowadays, this one-time honesty causes great surprise, because... Nowadays, even at the Olympic Games, it’s not very easy to be honest and not with everyone.

The first US politicians were also better than Boris Johnson - at least more educated and more intelligent. Thomas Jefferson, for example, also read Thucydides (and not only), and later said that he learned more from his History than from local newspapers. But he drew conclusions from his works that were opposite to those of Johnson. In Athens, he saw the tyranny of the all-powerful oligarchs and the crowd corrupted by their handouts, joyfully trampling on true heroes and patriots; in Sparta, the world's first constitutional state and the true equality of its citizens.

The "Founding Fathers" of the American state generally spoke of Athenian democracy as a terrible example of what should be avoided in the new country they led. But, ironically, contrary to their intentions, this is precisely the kind of state that ultimately emerged from the United States.

But since politicians who claim to be called serious are now comparing us to ancient Sparta, let’s try to understand its government structure, traditions and customs. And let’s try to understand whether this comparison should be considered offensive.

Trade, handicrafts, agriculture and other rough physical labor were indeed considered in Sparta to be occupations unworthy of a free person. A citizen of Sparta had to devote his time to more sublime things: gymnastics, poetry, music and singing (Sparta was even called the “city of beautiful choirs”). Result: the iconic “Iliad” and “Odyssey” were created for all of Hellas... No, not Homer, but Lycurgus: it was he who, having become acquainted with scattered songs attributed to Homer in Ionia, suggested that they were parts of two poems, and arranged them in “ necessary”, which has become canonical, order. This testimony of Plutarch, of course, cannot be considered the ultimate truth. But, without a doubt, he took this story from some sources that have not reached our time, which he completely trusted. And this version did not seem “wild”, absolutely impossible, unacceptable and unacceptable to any of his contemporaries. No one doubted the artistic taste of Lycurgus and his ability to act as a literary editor of the greatest poet of Hellas. Let's continue the story about Lycurgus. His name means “Wolf Courage”, and this is a real kening: the wolf is the sacred animal of Apollo, moreover, Apollo could turn into a wolf (as well as a dolphin, hawk, mouse, lizard and lion). That is, the name Lycurgus can mean "Courage of Apollo." Lycurgus was from the Dorian Euripontid family and could have become king after the death of his elder brother, but he gave up power in favor of his unborn child. That did not stop his enemies from accusing him of attempting to usurp power. And Lycurgus, like many other Hellenes suffering from excessive passionarity, went on a journey, visiting Crete, some policies of Greece and even Egypt. During this trip, he began to think about the reforms needed in his homeland. These reforms were so radical that Lycurgus considered it necessary to first consult one of the Delphic Pythia.

Eugene Delacroix, Lycurgus consults the Pythia

The soothsayer assured him that what he had planned would benefit Sparta - and now Lycurgus could no longer be stopped: he returned home and notified everyone of his desire to make Sparta great. Having heard about the need for reforms and transformations, the king, the same nephew of Lycurgus, quite logically assumed that he would now be killed a little - so that he would not stand in the way of progress and would not obscure the bright future of the people. And so he immediately ran to hide in the nearest temple. With great difficulty they pulled him out of this temple and forced him to listen to the newly-minted Messiah. Having learned that his uncle agreed to leave him on the throne as a puppet, the king sighed with relief and no longer listened to further speeches. Lycurgus established the Council of Elders and the College of Ephors, divided the land equally between all the Spartiates (there were 9,000 plots, which the helots assigned to them had to cultivate), prohibited the free circulation of gold and silver in Lacedaemon, as well as luxury goods, thereby practically eliminating many years of bribery and corruption. Now the Spartiates had to eat exclusively at joint meals (sissitia) - in public canteens assigned to each of the citizens for 15 people, to which they had to be very hungry: for poor appetite, the ephors could be deprived of citizenship. Citizenship was also lost to any Spartiate who could not pay the Sissitia fee on time. The food at these joint meals was plentiful, healthy, satisfying and coarse: wheat, barley, olive oil, meat, fish, wine diluted by 2/3. And, of course, the famous “black soup”. It consisted of water, vinegar, olive oil (not always), pork feet, pork blood, lentils, salt - according to numerous testimonies of contemporaries, foreigners could not even eat a spoonful. Plutarch claims that one of the Persian kings, having tasted this stew, said:

“Now I understand why the Spartans go to their death so bravely - they prefer death than such food.”

And the Spartan commander Pausanias, having tasted food prepared by Persian cooks after the victory at Plataea, said:

“Look how these people live! And marvel at their stupidity: having all the blessings of the world, they came from Asia to take away such pitiful crumbs from us...”

According to J. Swift, Gulliver didn’t like the black stew either. The third part of the book (“Journey to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Luggnegg, Glubbdobbrib and Japan”) talks, among other things, about summoning the spirits of famous people. Gulliver says:

“One helot, Agesilaus, cooked us a Spartan stew, but after tasting it, I could not swallow a second spoon.”

The Spartiates were equalized even after death: most of them, even the kings, were buried in unmarked graves. Only warriors who died in battle and women who died during childbirth were awarded a personal tombstone.

Now let's talk about the situation of the unfortunate helots and perieks, mourned many times by different authors. And upon closer examination it turns out that the Perieks of Lacedaemon lived very well. Yes, they could not participate in public assemblies, be elected to Gerusia and the college of ephors, and could not be hoplites - only soldiers of auxiliary units. It is unlikely that these restrictions affected them very much. Otherwise, they lived no worse, and often even better, than full-fledged citizens of Sparta: no one forced them to eat black stew in public “canteens,” children were not taken from their families to “boarding schools,” and they were not required to be heroes. Trade and various crafts provided a stable and very decent income, so that in the late period of the history of Sparta they turned out to be richer than many Spartiates. The Perieks, by the way, had their own slaves - not state slaves (helots), like the Spartiates, but personal, purchased ones. Which also indicates the fairly high welfare of the perieks. The helot farmers also did not suffer much, since, unlike the same “democratic” Athens, in Sparta there was no point in tearing three skins from slaves. Gold and silver were prohibited (the penalty for keeping them was death), hoarding bars of damaged iron (each weighing 625 g) did not even occur to anyone, and it was even impossible to eat normally in one’s home - poor appetite at joint meals, as we remember, he was punished. Therefore, the Spartiates did not demand much from the helots assigned to them. As a result, when King Cleomenes III offered the helots to gain personal freedom by paying five minas (more than 2 kg of silver), six thousand people were able to pay the ransom. In “democratic” Athens, the burden on the tax-paying classes was many times greater than in Sparta. The “love” of the Athenian slaves for their “democratic” masters was so great that when the Spartans occupied Dhekelia (a region north of Athens) during the Peloponnesian War, about 20,000 of these “helots” went over to the side of Sparta. But even the most severe exploitation of the local “helots” and “perieks” did not satisfy the demands of the aristocrats accustomed to luxury and the depraved ochlos; they actually had to plunder the allied policies, which very quickly realized how dearly Athenian democracy was costing them. Athens collected funds from the allied states for the “common cause,” which almost always turned out to be beneficial to Attica and only Attica. In 454 BC. the general treasury was transferred from Delos to Athens and was spent on decorating this city with new buildings and temples. At the expense of the union treasury, the Long Walls were built, connecting Athens with the port of Piraeus. In 454 BC. the amount of contributions from the allied policies was 460 talents, and in 425 - already 1460. To force the allies to loyalty, the Athenians created colonies on their lands - like in the lands of the barbarians. Athenian garrisons were stationed in especially unreliable cities. Attempts to leave the Delian League ended in “color revolutions” or direct military intervention of the Athenians (for example, in Naxos in 469, in Thasos in 465, in Euboea in 446, in Samos in 440–439 BC) In addition, They also extended the jurisdiction of the Athenian court (the “most fair” in Hellas, of course) to the territory of all their “allies” (who, rather, should still be called tributaries). The most “democratic” state in the modern “civilized world” – the USA – now treats its allies in approximately the same way. And friendship with Washington, which stands guard over “freedom and democracy,” is worth just as much. Only the victory of “totalitarian” Sparta in the Peloponnesian War saved 208 large and small Greek cities from humiliating dependence on Athens.

Children in Sparta were declared public property. Many stupid tales have been told about the upbringing of the boys of Sparta, which, alas, are still published even in school textbooks. Upon closer examination, these tales do not stand up to criticism and crumble literally before our eyes. In fact, studying in Spartan schools was so prestigious that they educated many children of noble foreigners, but not all of them - only those who had some merit to Sparta.

Edgar Degas, “Spartan girls challenge boys to a competition”

The system of raising boys was called "agoge" (literally translated from Greek - "withdrawal"). Upon reaching the age of 7 years, boys were taken from their families and handed over to mentors - experienced and authoritative Spartiates. They lived and were brought up in some kind of boarding schools (agels) until they were 20 years old. This should not be surprising, because in many countries the children of the elite were raised in much the same way - in closed schools and under special programs. The most striking example is Great Britain. Conditions in private schools for the children of bankers and lords there are still more than harsh; heating in the winter has not even been heard of, but until 1917, parents were annually charged money for rods. An outright ban on the use of corporal punishment in public schools in Britain was introduced only in 1986, and in private schools in 2003.

Caning in an English school, engraving

In addition, in British private schools it is considered normal what in the Russian army is called “hazing”: the unconditional submission of junior schoolchildren to older classmates - in Britain they believe that this strengthens the character of a gentleman and master, teaches to obey and command. The current heir to the throne, Prince Charles, once admitted that at the Scottish school Gordonstown he was beaten more often than others - they simply lined up: because everyone understood how pleasant it would be to later talk at the dinner table about how he punched the current king in the face. (Tuition fees at Gordonstown School: for children 8-13 years old - from £7,143 per term; for teenagers 14-16 years old - from 10,550 to 11,720 pounds per term).

Gordonstown School

The most famous and prestigious private school in Great Britain is Eton College. The Duke of Wellington even once said that "the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton."

Eton College

The disadvantage of the British education system in private schools is that pederasty is quite common in them. About the same Eton, the British themselves say that he “stands for three Bs: beating, bulling, buggery” - corporal punishment, hazing and sodomy. However, in the current Western value system, this “option” is more of an advantage than a disadvantage.

A little information: Eton is the most prestigious private school in England, into which children are admitted from the age of 13. The registration fee is £390, tuition fees for one term are £13,556, in addition, health insurance is paid for at £150 and a deposit is required to pay for running costs. In this case, it is very desirable that the child’s father is an Eton graduate. Eton alumni include 19 British Prime Ministers, as well as Princes William and Harry.

By the way, the famous Hoggwarts school from the Harry Potter novels is an idealized, “coiffed up” and politically correct example of a private English school.

In the Hindu states of India, the sons of rajas and nobility were raised far from home - in ashrams. The initiation ceremony as a disciple was considered as a second birth; submission to the Brahman mentor was absolute and unquestioning (such an ashram was reliably shown in the series "Mahabharata" on the "Culture" channel).

In continental Europe, girls of aristocratic families were sent to be raised in a monastery for several years, boys were given as squires, they sometimes worked along with servants, and no one stood on ceremony with them. Home education, until recently, has always been considered the lot of the “rabble.”

Thus, as we see now, and we will see in the future, nothing particularly terrible or out of bounds was done to the boys in Sparta: strict male upbringing, nothing more.

Now consider the now textbook, false story that weak or ugly children were thrown off a cliff. Meanwhile, in Lacedaemon there was a special class - the “hypomeions”, which initially included physically handicapped children of citizens of Sparta. They did not have the right to participate in the affairs of the state, but freely owned the property entitled to them by law and were engaged in economic affairs. The Spartan king Agesilaus limped since childhood, but this did not prevent him from not only surviving, but also becoming one of the most outstanding commanders of Antiquity.

By the way, archaeologists have found a gorge into which the Spartans allegedly threw defective children. And in it, indeed, human remains dating back to the 6th–5th centuries were discovered. BC e. – but not children, but 46 adult men aged 18 to 35 years. Probably, this ritual was carried out in Sparta only in relation to state criminals or traitors. And this was an exceptional punishment. For less serious offenses, foreigners were usually expelled from the country, and Spartiates were deprived of citizenship rights. For minor offenses that did not pose a great public danger, “punishment with shame” was imposed: the offender walked around the altar and sang a specially composed song that dishonored him.

Another example of “black PR” is a story about “preventative” weekly spankings to which all boys were allegedly subjected. In fact, in Sparta, once a year, a competition was held among boys at the temple of Artemis Orthia, which was called “diamastigosis”. The winner was the one who silently withstood the most blows of the whip.

Another historical myth: tales that Spartan boys were forced to earn their living by stealing, supposedly to acquire military skills. It’s very interesting: what kind of military skills that were useful to the Spartiates could be acquired in this way? The main force of the Spartan army was always heavily armed warriors - hoplites (from the words hoplon - large shield).

Spartan hoplites

The children of Spartan citizens were not trained for secret forays into the enemy camp in the style of Japanese ninjas, but for open battle as part of a phalanx. In Sparta, mentors did not even teach boys fighting techniques - “so that they would be proud not of art, but of valor.” When asked if he had seen good people anywhere, Diogenes replied: “Good people - nowhere, good children - in Sparta.” In Sparta, according to foreigners, it was “profitable only to grow old.” In Sparta, the one who first gave to him and made him a slacker was considered guilty of the shame of a beggar asking for alms. In Sparta, women had rights and freedom unprecedented and unheard of in the ancient World. In Sparta, prostitution was condemned and Aphrodite was contemptuously called Peribaso (“walking”) and Trimalitis (“pierced through”). Plutarch tells a parable about Sparta:

“They often remember, for example, the answer of the Spartan Gerad, who lived in very ancient times, to a foreigner. He asked what punishment they had for adulterers. “Foreigner, we have no adulterers,” Gerad objected. “What if they do show up?” “- the interlocutor did not concede. “The culprit will give in compensation a bull of such size that, stretching his neck out from behind Taygetus, he will get drunk in Eurota.” The stranger was surprised and said: “Where will such a bull come from?” - “And where will it come from in Sparta?” adulterer?" Gerad responded, laughing."

Of course, there were extramarital affairs in Sparta as well. But this story testifies to the presence of a social imperative that did not approve and condemn such connections.

And this Sparta raised its children to be thieves? Or are these tales about some other, mythical city, invented by the enemies of the real Sparta? And, in general, is it possible to raise children who are screwed half to death and intimidated by all sorts of prohibitions into confident citizens who love their homeland? Can the ever-hungry runaways, forced to steal a piece of bread, become fearsome healthy and strong hoplites?

Spartan Hoplite

If this story has any historical basis, then it can only relate to the children of the Perieks, for whom such skills could indeed be useful while serving in auxiliary units performing reconnaissance functions. And even among the Perieks, this was not supposed to be a system, but a ritual, a kind of initiation, after which the children moved to a higher level of education.

Now we will talk a little about homosexuality and pederastic pedophilia in Sparta and Greece.

The Ancient Customs of the Spartans (attributed to Plutarch) states:

“The Spartans were allowed to fall in love with honest-hearted boys, but to enter into a relationship with them was considered a disgrace, because such passion would be physical, not spiritual. A person accused of a shameful relationship with a boy was deprived of civil rights for life.”

Other ancient authors (in particular, Aelian) also testify that in the Spartan angels, unlike British private schools, real pederasty did not exist. Cicero, based on Greek sources, later wrote that hugs and kisses were allowed between the “inspirer” and the “listener” in Sparta, they were even allowed to sleep in the same bed, but in this case a cloak had to be placed between them.

If you believe the information given in the book “Sexual Life in Ancient Greece” by Licht Hans, the most that a decent man could afford in relation to a boy or young man was to place the penis between his thighs, and nothing more.

Here, Plutarch, for example, writes about the future king Agesilaus that “his beloved was Lysander.” What qualities attracted Lysander to the lame Agesilaus?

“Captured, first of all, by his natural restraint and modesty, for, shining among the young men with ardent zeal, the desire to be the first in everything... Agesilaus was distinguished by such obedience and meekness that he carried out all orders not out of fear, but out of conscience.”

The famous commander unmistakably found and distinguished among other teenagers the future great king and famous commander. And we are talking about mentoring, and not about banal sexual contacts.

In other Greek policies, such highly controversial relationships between men and boys were viewed differently. In Ionia, it was believed that pederasty dishonored a boy and deprived him of his masculinity. In Boeotia, on the contrary, the “relationship” of a young man with an adult man was considered almost normal. In Elis, teenagers entered into such relationships for gifts and money. On the island of Crete there was a custom of “kidnapping” a teenager by an adult man. In Athens, where promiscuity was perhaps the highest in Hellas, pederasty was tolerated, but only between adult men. At the same time, homosexual relationships were almost everywhere considered dishonorable to the passive partner. Thus, Aristotle claims that “a conspiracy was drawn up against Periander, the tyrant of Ambracia, because during a feast with his lover he asked him whether he had already become pregnant by him.”

The Romans, by the way, went even further in this regard: a passive homosexual (cynedus, patikus, concubinus) was equated in status to gladiators, actors and prostitutes, did not have the right to vote in elections and could not defend himself in court. Homosexual rape in all states of Greece and Rome was considered a serious crime.

But let's return to Sparta from the time of Lycurgus. When the first children raised according to his precepts became adults, the elderly legislator again went to Delphi. When leaving, he took an oath from his fellow citizens that no changes would be made to his laws until his return. At Delphi he refused to eat and died of hunger. Fearing that his remains would be transferred to Sparta, and the citizens would consider themselves free from the oath, before his death he ordered his corpse to be burned and the ashes thrown into the sea.

The historian Xenophon (IV century BC) wrote about the legacy of Lycurgus and the state structure of Sparta:

“The most surprising thing is that although everyone praises such institutions, not a single state wants to imitate them.”

Socrates and Plato believed that it was Sparta that showed the world “the ideal of the Greek civilization of virtue.” Plato saw in Sparta the desired balance of aristocracy and democracy: the full implementation of each of these principles of state organization, according to the philosopher, inevitably leads to degeneration and death. His student Aristotle considered the comprehensive power of the ephorate to be a sign of a tyrannical type of state, but the election of ephors was a sign of a democratic state. As a result, he came to the conclusion that Sparta should be recognized as an aristocratic state, and not a tyranny.

The Roman Polybius compared the Spartan kings with consuls, Gerusia with the Senate, and the ephors with tribunes.

Much later, Rousseau wrote that Sparta was not a republic of people, but of demigods.

Many historians believe that modern concepts of military honor came to European armies from Sparta

Sparta maintained its unique state structure for a very long time, but this could not continue forever. Sparta was ruined, on the one hand, by the desire not to change anything in the state in a constantly changing world, on the other hand, by forced half-hearted reforms that only worsened the situation.

As we remember, Lycurgus divided the land of Lacedaemon into 9000 parts. Subsequently, these plots began to rapidly fragment, since after the death of the father they were divided between his sons. And, at some point, it suddenly turned out that one of the Spartiates did not have enough income from the inherited land even to pay the obligatory contribution to the syssitia. And a full-fledged law-abiding citizen automatically passed into the category of hypomeion ("junior" or even, in another translation, "degraded"): he no longer had the right to participate in public assemblies and hold any public office.

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), in which the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta defeated Athens and the Delian League, greatly enriched Lacedaemon. But this victory, paradoxically, only worsened the situation in the country of the winners. Sparta had so much gold that the ephors lifted the ban on owning silver and gold coins, but citizens could only use them outside Lacedaemon. The Spartans began to store their savings in allied cities or in temples. And many rich young Spartans now preferred to “enjoy life” outside Lacedaemon

Around 400 BC e. in Lacedaemon, the sale of hereditary land was allowed, which instantly ended up in the hands of the richest and most influential Spartiates. As a result, according to Plutarch, the number of full-fledged citizens of Sparta (of which there were 9,000 people under Lycurgus) decreased to 700 (the main wealth was concentrated in the hands of 100 of them), the remaining rights of citizenship were lost. And many bankrupt Spartiates left their homeland to serve as mercenaries in other Greek city-states and in Persia.

In both cases, the result was the same: Sparta lost healthy, strong men - both rich and poor, and became weaker.

In 398 BC, the Spartiates, who had lost their land, led by Kidon, tried to rebel against the new order, but were defeated.

The logical result of the comprehensive crisis that engulfed Sparta, which was losing its vitality, was the temporary subordination of Macedonia. Spartan troops did not participate in the famous Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), in which Philip II defeated the combined army of Athens and Thebes. But in 331 BC. the future diadokh Antipater defeated Sparta in the Battle of Megaloprolus - about a quarter of the full-fledged Spartiates and King Agis III died. This defeat forever undermined the power of Sparta, ending its hegemony in Hellas, and, consequently, significantly reducing the flow of money and funds from its allied states. The property stratification of citizens that had previously emerged grew rapidly, the state finally split, continuing to lose people and strength. In the 4th century. BC The war against the Boeotian League turned into a disaster, whose commanders Epaminondas and Pelapidas finally dispelled the myth of the invincibility of the Spartiates.

In the 3rd century. BC. The Hagiad kings Agis IV and Cleomenes III tried to rectify the situation. Agis IV, who ascended the throne in 245 BC, decided to give citizenship to part of the Perieks and worthy foreigners, ordered to burn all debt obligations and redistribute land plots, setting an example by transferring all his lands and all property to the state. But already in 241 he was accused of striving for tyranny and sentenced to death. The Spartiates, who had lost their passion, remained indifferent to the execution of the reformer. Cleomenes III (became king in 235 BC) went even further: he killed 4 ephors who interfered with him, dissolved the Council of Elders, abolished debts, freed 6,000 helots for ransom and gave citizenship rights to 4 thousand perieks. He redistributed the land again, expelling the 80 richest landowners from Sparta and creating 4,000 new plots. He managed to subjugate the eastern part of the Peloponnese to Sparta, but in 222 BC. his army was defeated by the combined army of a new coalition of cities of the Achaean League and their Macedonian allies. Laconia was occupied, reforms were canceled. Cleomenes was forced to go into exile in Alexandria, where he died. The last attempt to revive Sparta was made by Nabis (ruled 207-192 BC). He declared himself a descendant of King Demaratus from the Euripontid family, but many contemporaries and later historians considered him a tyrant - that is, a person who had no right to the royal throne. Nabis destroyed the relatives of the Spartan kings of both dynasties, expelled the rich and requisitioned their property. But he freed many slaves without any conditions and gave refuge to everyone who fled to him from other policies of Greece. As a result, Sparta lost its elite; the state was ruled by Nabis and his henchmen. He managed to capture Argos, but in 195 BC. the allied Greco-Roman army defeated the army of Sparta, which now lost not only Argos, but also its main seaport - Gytium. In 192 BC. Nabis died, after which royal power in Sparta was finally abolished, and Lacedaemon was forced to join the Achaean League. In 147 BC, at the request of Rome, Sparta, Corinth, Argos, Heraclea and Orchomenus were withdrawn from the union. And the following year, the Roman province of Achaia was founded throughout Greece.

The Spartan army and the military history of Sparta will be discussed in more detail in the next article.

Ctrl Enter

Noticed osh Y bku Select text and click Ctrl+Enter

Among the many ancient Greek states, two stood out - Laconia or Laconia (Sparta) and Attica (Athens). At their core, these were antagonistic states with social systems opposing each other.

Sparta of Ancient Greece existed in the southern lands of the Peloponnese from the 9th to the 2nd centuries BC. e. It is notable for the fact that it was ruled by two kings. They passed on their power by inheritance. However, real administrative power belonged to the elders. They were chosen from among respected Spartans who were at least 50 years old.

Sparta on the map of Greece

It was the council that decided all state affairs. As for the kings, they performed purely military functions, that is, they were commanders of the army. Moreover, when one king went on a campaign, the second remained in the city with part of the soldiers.

An example here would be the king Lycurgus, although it is not known for sure whether he was a king or simply belonged to the royal family and had enormous authority. The ancient historians Plutarch and Herodotus wrote that he was the ruler of the state, but did not specify what position this man held.

The activities of Lycurgus dated back to the first half of the 9th century BC. e. It was under him that laws were passed that did not give citizens the opportunity to enrich themselves. Therefore, in Spartan society there was no stratification of property.

All land suitable for plowing was divided into equal plots, which were called clerks. Each family received an allotment. He provided people with barley flour, wine and vegetable oil. According to the legislator, this was quite enough to lead a normal life.

Luxury was relentlessly pursued. Gold and silver coins were even withdrawn from circulation. Crafts and trade were also banned. The sale of agricultural surpluses was prohibited. That is, under Lycurgus, everything was done to prevent people from earning too much.

The main occupation of the Spartan state was considered to be war. It was the conquered peoples who provided the conquerors with everything necessary for life. And on the land plots of the Spartans slaves worked, who were called helots.

The entire society of Sparta was divided into military units. In each of them, joint meals were practiced or sissity. People ate from a common pot and brought food from home. During the meal, the detachment commanders made sure that all portions were eaten. If someone ate poorly and without appetite, then the suspicion arose that the person had eaten heavily somewhere on the side. The offender could be expelled from the detachment or punished with a large fine.

Spartan warriors armed with spears

All the men of Sparta were warriors, and they were taught the art of war from early childhood. It was believed that a mortally wounded warrior should die silently, without even uttering a quiet groan. The Spartan phalanx, bristling with long spears, terrified all the states of Ancient Greece.

Mothers and wives, seeing off their sons and husbands to war, said: “With a shield or on a shield.” This meant that the men were expected to go home either victorious or dead. The bodies of the dead were always carried by comrades on shields. But those who ran away from the battlefield faced universal contempt and shame. Parents, wives, and their own children turned away from them.

It should be noted that the inhabitants of Laconia (Laconia) were never known for their verbosity. They expressed themselves briefly and to the point. It was from these Greek lands that such terms as “laconic speech” and “laconicism” spread.

It must be said that Sparta of Ancient Greece had a very small population. Its population over the centuries has consistently not exceeded 10 thousand people. However, this small number of people kept all the southern and middle lands of the Balkan Peninsula in fear. And such superiority was achieved through cruel customs.

When a boy was born into a family, he was examined by the elders. If the baby turned out to be too frail or sick in appearance, then he was thrown from the cliff onto sharp stones. The corpse of the unfortunate man was immediately eaten by birds of prey.

The customs of the Spartans were extremely cruel

Only healthy and strong children remained alive. Upon reaching the age of 7, boys were taken from their parents and united into small units. Iron discipline reigned in them. Future warriors were taught to endure pain, bravely endure beatings, and unquestioningly obey their mentors.

At times, children were not fed at all, and they had to earn their own food by hunting or stealing. If such a child was caught in someone’s garden, he was severely punished, but not for theft, but for the fact that he was caught.

This barracks life continued until the age of 20. After this, the young man was given a land plot, and he had the opportunity to start a family. It should be noted that Spartan girls were also trained in the art of war, but not in such harsh conditions as the boys.

Sunset of Sparta

Although the conquered peoples were afraid of the Spartans, they periodically rebelled against them. And although the conquerors had excellent military training, they were not always victorious.

An example here is the uprising in Messenia in the 7th century BC. e. It was headed by the fearless warrior Aristomenes. Under his leadership, several sensitive defeats were inflicted on the Spartan phalanx.

However, there were traitors in the ranks of the rebels. Thanks to their betrayal, Aristomenes’s army was defeated, and the fearless warrior himself began a guerrilla war. One night he made his way to Sparta, entered the main sanctuary and, wanting to shame his enemies before the gods, left on the altar the weapons taken from the Spartan warriors in battle. This shame remained in the memory of people for centuries.

In the 4th century BC. e. Sparta of Ancient Greece began to gradually weaken. Other nations entered the political arena, led by smart and talented commanders. Here we can name Philip of Macedon and his famous son Alexander the Great. The inhabitants of Laconia became completely dependent on these prominent political figures of antiquity.

Then it was the turn of the Roman Republic. In 146 BC. e. The Spartans submitted to Rome. However, formally freedom was preserved, but under the complete control of the Romans. In principle, this date is considered the end of the Spartan state. It has become history, but has been preserved in people’s memory to this day.

There is probably no person who has not heard of the ancient city-state of Sparta. When you mention this country, you certainly think about the strength, courage and pride of the people who inhabited it. The history and culture of Ancient Sparta has been haunting scientists for several millennia, trying to understand the foundations of greatness and the reasons for the fall of one of the first states on the planet. Let's try to figure this out too.

Geographical position

Without an answer to the question of where ancient Sparta was located, it is impossible to understand all the benefits of the socio-economic and political location of this state. It was located in the south of the Peloponnesian Peninsula in the region of Laconia (present-day territory of Greece). Its expanses were washed by two seas - the Aegean and the Ionian - which opened paths for the Spartans in naval campaigns and easy passage of profit after wars of conquest. At the time of its heyday, the territory of Sparta occupied about 8 thousand square kilometers. It was the greatest power of those times, which allowed it not to build fortifications and defensive walls for several centuries.

Unusual name

The city received its name in honor of the wife of the ancient Greek mythological character Lacedaemon - Sparta. The historical documents of the philosopher Plutarch say that Lacedaemon was the king of Laconia. He believed that his father was Zeus, and his mother was the Pleiad Tiageda. He ruled for a long time, and in connection with this, a synonym for the word “Sparta” arose - Lacedaemon. True, the historian did not leave any facts about his political or military successes.

Founding of the country

The ancient history of Sparta begins its page from the 11th century BC, when the territory of Laconia was settled by the Achaeans, displacing the Leleg people who lived there, and waged wars to conquer nearby cities - Argos, Arcadia and Messenia. The Spartans showed unprecedented kindness by not destroying the vanquished. They turned them into slaves and called them helots, which literally means “captives.”

Laws of Lycurgus

The law of Ancient Sparta is inextricably linked with the name of Lycurgus, an ancient Spartan public figure. Little is known about his life, but his laws are still talked about, because it was on them that the legal institute of Sparta was built. The laws were in the form of retra - short forms of legal sayings passed from mouth to mouth. They learned by heart. There were 4 retras: 1 large and three small. One of the minor retras prohibited the publication of laws in writing. This was done so that the ruling aristocracy would not limit its capabilities to the text of the law, but could always turn the wording of the document in its direction. The retras of Lycurgus strictly limited and controlled all areas of the life of the Spartans.

Restrictions controlled by retros

To avoid social inequality, the Spartans did not use monetary units. All material transactions were carried out through exchange. It was forbidden to carry out commercial manipulations with the land. In order not to lead people astray with luxury items, the Spartans were forbidden to use beautiful things or jewelry. It was also prohibited to produce these items.

Features of family life in Sparta

As the history of Ancient Sparta tells, family life also fell under the eye of Lycurgus' law. A man could only marry after 16 years of age, but he spent little time with his family. The main part of life was occupied not by family, but by military service. The children did not belong to their parents. From the age of 7, they were taken from their families and a fighting spirit was instilled in them: they were fed poorly, given one tunic for a year, and after graduating from school, the young men had to pass a kind of exam - caning, during which they were not allowed to scream or ask for help. A feature of Spartan matrimonial law is divorce. True, only a man could ask the elders to break family ties. This happened in two cases: if the woman cheated on her spouse or was infertile.

Asceticism is the head of everything

The life of Ancient Sparta was subject to control and order in everything. Legends still circulate about Spartan asceticism. Even aristocrats tried to limit themselves in food. From childhood, girls were raised as future mothers and wives for the military. Those, in turn, always wore a dark red tunic to battle, so that in case of injury no one would dare to blame the warrior for weakness from hemorrhage. Often, they preferred a quiet death on the battlefield, because asking for help from a medic was considered a sin. Just look at the legend that the Spartans threw weak and undeveloped children from the top of the mountain. This story was believed by many for three thousand years, until scientists refuted this fact by saying that only the bones of adults were found in the mountain gorge.

State system of Sparta

Lycurgus is also credited with creating the ladder of government. Despite the fact that most scientists classify the Spartans as illiterate peoples, the political system of Ancient Sparta was much more advanced than that of other ancient Greek states.

Sparta was ruled by two kings: representatives of different dynasties enjoyed great respect among their subjects. The kings ruled the army, but only one of the monarchs went to war, the other remained in the city and led peaceful life, was engaged in providing the rear with provisions and preparing weapons for future reinforcement of the army.

The names, as well as the duties, of the kings were different:

- basileus - a ruler not involved in hostilities,

- archegate - a militant Spartan king.

These two rulers were part of the gerusia - a meeting of elders who, through discussion, solved the pressing problems of the state. Since representatives of the two warring families were constantly in quarrels and strife, they began to lose their influence over their subjects. Over time, they became a representative monarchy, and real power was concentrated in the hands of the ephors. But this did not at all prevent the kings of Ancient Sparta from having their own honor and receiving good income from the local population in the form of plots of land, sacrificial food and charitable money.

Gerousia, like a relic of the past

28 men over 60 years of age were elected to the gerousia. They discussed important state affairs, and under some kings they could even veto his decisions. Over time, this legislative body lost its opportunity to influence the political system and switched to judicial practice. They considered criminal cases, passed sentences, discussed how best to punish the culprit, and dealt especially harshly with traitors to the motherland.

People's Assemblies (appellas)

The congregations included men who were over 30 years old and born into aristocratic families. At the meeting, the ephors were chosen, which of the kings would go on a military campaign, and who would take the throne if there was no heir to the throne. Also, the final decision to deprive traitors of citizenship was made here. They also made the decision to grant citizenship to a person if he expressed such a desire. True, wisdom did not allow the participants in the appeal to agree on voting methods, because, more often than not, the one who shouted loudest or persuaded others to defend their opinion turned out to be right.

Ephors

The most powerful government officials were elected every 8 years. In total, 5 people were selected for this period. To honor and glorify the ephors throughout the centuries, the apelae named a calendar year in honor of each of them. They controlled all activities and all government officials.

During hostilities, two ephors accompanied the king to prevent him from profiting from military affairs or, what is much worse, showing his cowardice on the battlefield. Often these people turned into dictators, since the lack of written laws could not limit their desires. They could even expel the king so as not to carry out his orders. To do this, they made predictions from the priests from time to time. If the king's rule suited the ephors, then the omen most often turned out to be good, and if not, then the prediction led to the quick expulsion or murder of the king.

What is special about Sparta?

The features of Ancient Sparta are associated only with military affairs. In this country, tactical deployment of soldiers was first developed, which often led to victories. From birth, a Spartan was raised for battle, so he went into a terrible battle with a wreath on his head, so that in case of death he would be worthy of burial. For these people, such qualities as cowardice, faint-heartedness or indifference to the fate of their country were incomprehensible.

Deserters were despised, but their lives were spared so that they would suffer for the rest of their lives for the crime they had previously committed against the country. They had special bandages sewn on them and their hair done so that no one could even talk to them. The children of the traitors also could not build their own families, since they were already tainted from birth with dislike for Sparta. Even people who were interested in books or art were declared cowards in this country, and soon outcasts. Maybe that's why not a single famous artist or philosopher was born in Sparta.

Helots

The peasants of Ancient Sparta were called helots. Helots are the local population that was captured by the Spartans at the dawn of the formation of the state. Since the Spartans were busy on military campaigns, the helots were engaged in cultivating the sovereign's lands, caring for and harvesting crops. True, they did not give away the entire part of the harvest, but only a certain share of it. This part was fixed, and in modern words it can be called a tax. There are no historical documents available about its size. This allowed the helots to live, although poorly, but not die of hunger.

They obeyed only one person - their master. But their rights and obligations were regulated at the state level. The helot differed from the classic slave in the right to have a family life and the opportunity to save money. He had his own house, which was passed down by inheritance. In criminal law, helots were not treated on ceremony. He could be executed, flogged, or have part of his body amputated for the slightest mistake. In order not to make an internal enemy, the Spartans sought to keep the number of helots no more than half a million people.

Culture

The culture of Ancient Sparta is not diverse. People who were unable to engage in military affairs were despised. Practicing art, writing, and philosophy was ridiculed. The population was illiterate, and even though reading and writing were taught in military schools, future soldiers could skip lessons in order to hone their physical strength. The only cultural element was patriotic songs. They were memorized and sung during the military campaign.

Not everyone was allowed to sing patriotic songs. The words in these songs are quite simple, but each phrase is aimed at raising a person's fighting spirit. Religion was an important indicator of culture. The Spartans believed in the ancient Greek gods. Without a religious cult, not a single campaign was carried out, and not a single battle began. Before the battle, sacrifices were made to the gods so that they would be on the side of the warriors during the battle. After the end of the battle, regardless of the results, religious praise was given to the gods.

Olympic Games of Ancient Sparta

It was an honor for any Spartan to take part in the Olympic Games. For many years they were first in the number of victories. The athletes of Sparta adhered to a sports regime and trained intensively. Did not take part in fist fights. After all, in case of loss, it was necessary to admit one’s weakness, which was not compared with the moral principles of the Spartans. It was at the Olympics that European city-countries began to follow the example of the physical fitness of athletes from Sparta.

Encyclopedic YouTube

State structure

Ancient Sparta- an example of an aristocratic state, which, in order to suppress the huge mass of the forced population (helots), artificially restrained the development of private property and unsuccessfully tried to maintain equality among the Spartans themselves. The basis for the emergence of the state in Sparta, usually attributed to the 8th-7th centuries. BC e., there were general patterns of decomposition of the primitive communal system. The organization of political power among the Spartans was typical for the period of the collapse of the primitive communal system: two tribal leaders (possibly as a result of the unification of the Achaean and Dorian tribes), a council of elders, and a national assembly. In the VI century. BC e. the so-called “Lycurgian system” developed (establishment of heloty, strengthening the influence of the community of Sparta by equalizing them economically and politically and turning this community into a military camp). At the head of the state were two archagets, who were chosen every eight years by divination by the stars. The army was subordinate to them, and they had the right to most of the spoils of war, and had the right of life and death in campaigns.

Positions and authorities:

Story

Prehistoric era

The Achaeans from the royal family related to the Perseids arrived in the Laconian lands, where the Leleges originally lived, whose place was later taken by the Pelopids. After the conquest of the Peloponnese by the Dorians, Laconia, the least fertile and insignificant region, as a result of deception, went to the minor sons of Aristodemus, Eurysthenes and Proclus from the Heraclidean family. From them came the dynasties of the Agiads (on behalf of Agis, the son of Eurysthenes) and the Euripontides (on behalf of Eurypontus, the grandson of Proclus).

The main city of Laconia soon became Sparta, located near the ancient Amycles, which, like the rest of the Achaean cities, lost their political rights. Along with the dominant Dorians and Spar dances, the population of the country consisted of Achaeans, among whom were the Periecians (ancient Greek. περίοικοι ) - deprived of political rights, but personally free and having the right to own property, and helots - deprived of their land plots and turned into slaves. For a long time, Sparta did not stand out among the Doric states. She waged external wars with neighboring Argive and Arcadian cities. The rise of Sparta began with the times of Lycurgus and the Messenian Wars.

Archaic era

With the victory in the Messenian Wars (743-723 and 685-668 BC), Sparta managed to finally conquer Messenia, after which the ancient Messenians were deprived of their land holdings and turned into helots. The fact that there was no peace within the country at that time is evidenced by the violent death of King Polydor, the expansion of the powers of the ephors, which led to the limitation of royal power, and the expulsion of the Parthenias, which were founded under the command of Phalanthos in 707 BC. e. Tarentum. However, when Sparta, after difficult wars, defeated the Arcadians, especially when shortly after 660 BC. e. forced Tegea to recognize its hegemony, and according to the agreement, which was kept on a column placed near Althea, forced to conclude a military alliance, since then Sparta was considered in the eyes of the people the first state of Greece. The Spartans impressed their admirers by trying to overthrow the tyrants who, from the 7th century BC. e. appeared in almost all Greek states. The Spartans contributed to the expulsion of the Cypselids from Corinth and the Pisistrati from Athens, and liberated Sikyon, Phocis and several islands of the Aegean Sea. Thus, the Spartans acquired grateful and noble supporters in different states.

Argos competed with Sparta for the championship for the longest time. However, when the Spartans in 550 BC. e. conquered the border region of Kynuria with the city of Thyreus, king Cleomenes around 520 BC. e. inflicted a decisive defeat on the Argives at Tiryns, and from then on Argos kept away from all areas controlled by Sparta.

Classical era

First of all, the Spartans entered into an alliance with Elis and Tegea, and then won over the policies of the rest of the Peloponnese. In the resulting Peloponnesian League, hegemony belonged to Sparta, which provided leadership in the war and was also the center of meetings and conferences of the Union. At the same time, it did not encroach on the independence of individual states, which retained their autonomy. Also, the allied states did not pay dues to Sparta (ancient Greek. φόρος ), there was no permanent union council, but if necessary it was convened in Sparta (ancient Greek. παρακαλειν ). Sparta did not try to extend its power to the entire Peloponnese, but the general danger during the Greco-Persian Wars pushed all states except Argos to come under the command of Sparta. With the immediate danger removed, the Spartans realized that they could not continue the war with the Persians far from their borders, and when Pausanias and Leotychides disgraced the Spartan name, the Spartans were forced to allow Athens to take further leadership in the war and confine themselves to the Peloponnese . Over time, rivalry between Sparta and Athens began to emerge, resulting in the First Peloponnesian War, which ended with the Thirty Years' Peace.

The growth of the power of Athens and its expansion to the west in 431 BC. e. led to the Peloponnesian War. It broke the power of Athens and led to the establishment of the hegemony of Sparta. At the same time, the foundations of Sparta began to be violated - the legislation of Lycurgus.

From the desire of non-citizens for full rights, 397 BC. e. The Kinadon uprising occurred, but was not successful. Agesilaus tried to extend the established power in Greece to Asia Minor and successfully fought against the Persians until the Persians provoked the Corinthian War in 395 BC. e. After several failures, especially after the defeat in the naval battle of Cnidus (394 BC), Sparta, wanting to take advantage of the successes of the weapons of its opponents, ceded Asia Minor to the king of Antalkidov, recognized him as a mediator and judge in Greek affairs and, thus, under the pretext of the freedom of all states, it secured primacy in an alliance with Persia. Only Thebes did not submit to these conditions and deprived Sparta of the benefits of a shameful peace. Athens with victory at Naxos 376 BC. e. concluded a new alliance (see Second Athenian Naval Alliance), and Sparta in 372 BC. e. formally succumbed to hegemony. Even greater misfortune befell Sparta in the subsequent Boeotian War. Epaminondas dealt the final blow to the city with the restoration of Messenia in 369 BC. e. and the formation of Megalopolis, therefore in 365 BC. e. The Spartans were forced to allow their allies to conclude a separate peace with Thebes.

Hellenistic and Roman era

From this time on, Sparta quickly began to decline, and due to the impoverishment and burden of citizens with debts, the laws turned into an empty form. An alliance with the Phocaeans, to whom the Spartans sent help but did not provide actual support, arming Philip of Macedon against them, who appeared in 334 BC. e. in the Peloponnese and approved the independence of Messenia, Argos and Arcadia, however, on the other hand, he did not pay attention to the fact that ambassadors were not sent to the Corinthian collections. In the absence of Alexander the Great, King Agis III, with the help of money received from Darius, tried to throw off the Macedonian yoke, but was defeated by Antipater at Megalopolis and was killed in battle. The fact that little by little the famous Spartan warlike spirit also disappeared is shown by the presence of fortifications of the city during the attacks of Demetrius Poliorcetes (296 BC) and Pyrrhus of Epirus (272 BC).

The “System of Lycurgus” transformed the military democracy of the Spartiates into an oligarchic slave-owning republic, which retained the features of the tribal system. At the head of the state there were simultaneously two kings - archagets. Their power was hereditary. The powers of the archaget were limited to military power, organization of sacrifices and participation in the council of elders.

The Gerusia (council of elders) consisted of two archagets and 28 geronts, who were elected for life by a popular assembly of noble citizens who had reached the age of 60. Gerusia performed the functions of a government agency - it prepared issues for discussion at public meetings, directed foreign policy, and considered criminal cases of state crimes (including crimes against the archaget).

Unlike other Greek states, the Spartans did not have military formations, made up of lovers .

Education system

Birth

The father had to take the newborn to the elders. Sick or premature children were thrown from a cliff, which had the allegorical name “Vault” ( ἀποθέται ) . It is believed that this practice was a primitive form of eugenics. The practice of infanticide at this time occurred not only in Sparta, but also in other regions of Greece, including Athens. At the same time, some archaeologists note the absence of children's remains in the abyss where Spartan children were allegedly thrown.

Upbringing

The education of the younger generation was considered in classical Sparta (until the 4th century BC) a matter of national importance. The education system was subordinated to the task of physical development of citizen-soldiers. Among moral qualities, emphasis was placed on determination, perseverance and loyalty. From 7 to 20 years old, the sons of free citizens lived in military-type boarding schools. In addition to physical exercises and hardening, war games, music and singing were practiced. The skills of clear and concise speech (“laconic” - from Laconius) were developed. All children in Sparta were considered property of the state. Severe upbringing, focused on endurance, is still called Spartan.

Legacy of Sparta

Sparta left its most significant legacy in military affairs. Discipline is a necessary element of any modern army. The battle formation of the Spartans is the predecessor of the phalanx of the army of Alexander the Great.

Sparta also had a significant influence on the humanitarian spheres of human life. The Spartan state is a prototype of the ideal state described in the dialogues by Plato. The courage of the “three hundred Spartans” at the Battle of Thermopylae has been the theme of many literary works and modern films. Word laconic, meaning a man of few words, comes from the name of the Spartan country of Laconia.

Famous Spartans

- Agesilaus II - king of Sparta from 401 BC. e., an outstanding commander of the ancient world.