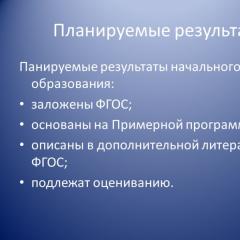

Tolstoy Lev Nikolaevich Bulka (Stories of an officer). Bulka - Leo Tolstoy Respect old people

Page 1 of 3

I had a little face... Her name was Bulka. She was all black, only the tips of her front paws were white.

I had a little face... Her name was Bulka. She was all black, only the tips of her front paws were white.

In all faces, the lower jaw is longer than the upper and the upper teeth extend beyond the lower ones; but Bulka’s lower jaw protruded forward so much that a finger could be placed between the lower and upper teeth. Bulka's face was wide; the eyes are large, black and shiny; and white teeth and fangs always stuck out. He looked like a blackamoor. Bulka was quiet and did not bite, but he was very strong and tenacious. When he would cling to something, he would clench his teeth and hang like a rag, and, like a tick, he could not be torn off.

Once they let him attack a bear, and he grabbed the bear’s ear and hung like a leech. The bear beat him with his paws, pressed him to himself, threw him from side to side, but could not tear him away and fell on his head to crush Bulka; but Bulka held on to it until they poured cold water on him.

I took him as a puppy and raised him myself. When I went to serve in the Caucasus, I didn’t want to take him and left him quietly, and ordered him to be locked up. At the first station, I was about to board another transfer station, when suddenly I saw something black and shiny rolling along the road. It was Bulka in his copper collar. He flew at full speed towards the station. He rushed towards me, licked my hand and stretched out in the shadows under the cart. His tongue stuck out the entire palm of his hand. He then pulled it back, swallowing drool, then again stuck it out to the whole palm. He was in a hurry, did not have time to breathe, his sides were jumping. He turned from side to side and tapped his tail on the ground.

I found out later that after me he broke through the frame and jumped out of the window and, right in my wake, galloped along the road and rode like that for twenty miles in the heat.

Bulka and boar

Once in the Caucasus we went boar hunting, and Bulka came running with me. As soon as the hounds started driving, Bulka rushed towards their voice and disappeared into the forest. This was in November: wild boars and pigs are very fat then.

In the Caucasus, in the forests where wild boars live, there are many delicious fruits: wild grapes, cones, apples, pears, blackberries, acorns, blackthorns. And when all these fruits are ripe and touched by frost, the wild boars eat up and grow fat.

At that time, the boar is so fat that it cannot run under the dogs for long. When they have been chasing him for two hours, he gets stuck in a thicket and stops. Then the hunters run to the place where he stands and shoot. You can tell by the barking of dogs whether a boar has stopped or is running. If he runs, the dogs bark and squeal, as if they are being beaten; and if he stands, then they bark as if at a person and howl.

During this hunt I ran through the forest for a long time, but not once did I manage to cross the path of the boar. Finally, I heard the prolonged barking and howling of hound dogs and ran to that place. I was already close to the wild boar. I could already hear more frequent crackling sounds. It was a boar with dogs tossing and turning. But you could hear from the barking that they did not take him, but only circled around him. Suddenly I heard something rustling from behind and saw Bulka. He apparently lost the hounds in the forest and got confused, and now he heard their barking and, just like me, he rolled in that direction as fast as he could. He ran across the clearing, through the tall grass, and all I could see from him was his black head and his tongue bitten between his white teeth. I called out to him, but he did not look back, overtook me and disappeared into the thicket. I ran after him, but the further I walked, the more dense the forest became. Twigs knocked my hat off, hit me in the face, thorn needles clung to my dress. I was already close to barking, but I couldn’t see anything.

Suddenly I heard the dogs bark louder, something crackled loudly, and the boar began to puff and wheeze. I thought that now Bulka had gotten to him and was messing with him. With all my strength I ran through the thicket to that place. In the deepest thicket I saw a motley hound dog. She barked and howled in one place, and three steps away from her something was fussing and turning black.

When I moved closer, I examined the boar and heard Bulka squeal piercingly. The boar grunted and leaned towards the hound - the hound tucked its tail and jumped away. I could see the side of the boar and its head. I aimed at the side and fired. I saw that I got it. The boar grunted and rattled away from me more often. The dogs squealed and barked after him, and I rushed after them more often. Suddenly, almost under my feet, I saw and heard something. It was Bulka. He lay on his side and screamed. There was a pool of blood underneath him. I thought, “The dog is missing”; but I had no time for him now, I pressed on. Soon I saw a wild boar. The dogs grabbed him from behind, and he turned to one side or the other. When the boar saw me, he poked his head towards me. I shot another time, almost point-blank, so that the bristles on the boar caught fire, and the boar wheezed, staggered, and the whole carcass slammed heavily to the ground.

When I approached, the boar was already dead and was only heaving and twitching here and there. But the dogs, bristling, some tore at his belly and legs, while others lapped up the blood from the wound.

Then I remembered about Bulka and went to look for him. He crawled towards me and moaned. I walked up to him, sat down and looked at his wound. His stomach was torn open, and a whole lump of intestines from his stomach was dragging along the dry leaves. When my comrades came to me, we set Bulka’s intestines and sewed up his stomach. While they were stitching up my stomach and piercing the skin, he kept licking my hands.

They tied the boar to the horse's tail to take it out of the forest, and they put Bulka on the horse and brought him home.

Bulka was ill for six weeks and recovered.

Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy

Bulka

(Officer's stories)

BULKA

I had a face. Her name was Bulka. She was all black, only the tips of her front paws were white.

In all faces, the lower jaw is longer than the upper, and the upper teeth extend beyond the lower ones; but Bulka’s lower jaw protruded forward so much that a finger could be placed between the lower and upper teeth. Bulka's face was wide, her eyes were large, black and shiny; and white teeth and fangs always stuck out. He looked like a blackamoor. Bulka was quiet and did not bite, but he was very strong and tenacious. When he would cling to something, he would clench his teeth and hang like a rag, and, like a tick, he could not be torn off.

Once they let him attack a bear, and he grabbed the bear’s ear and hung like a leech. The bear beat him with his paws, pressed him to himself, threw him from side to side, but could not tear him away and fell on his head to crush Bulka; but Bulka held on to it until they poured cold water on him.

I took him as a puppy and raised him myself. When I went to serve in the Caucasus, I didn’t want to take him and left him quietly, and ordered him to be locked up. At the first station, I wanted to board another crossbar [Pereknaya - a carriage drawn by horses, which changed at postal stations; “were traveling on crossroads” in Russia before the construction of railways], when suddenly I saw something black and shiny rolling along the road. It was Bulka in his copper collar. He flew at full speed towards the station. He rushed towards me, licked my hand and stretched out in the shadows under the cart.

His tongue stuck out the entire palm of his hand. He then pulled it back, swallowing drool, then again stuck it out to the whole palm. He was in a hurry, did not have time to breathe, his sides were jumping. He turned from side to side and tapped his tail on the ground.

I found out later that after me he broke through the frame and jumped out of the window and, right in my wake, galloped along the road and rode like that for twenty miles in the heat.

BULKA AND BOAR

Once in the Caucasus we went boar hunting, and Bulka came running with me. As soon as the hounds started driving, Bulka rushed towards their voice and disappeared into the forest. This was in November: wild boars and pigs are very fat then.

In the Caucasus, in the forests where wild boars live, there are many delicious fruits: wild grapes, cones, apples, pears, blackberries, acorns, blackthorns. And when all these fruits are ripe and touched by frost, the wild boars eat up and grow fat.

At that time, the boar is so fat that it cannot run under the dogs for long. When they have been chasing him for two hours, he gets stuck in a thicket and stops. Then the hunters run to the place where he stands and shoot. You can tell by the barking of dogs whether a boar has stopped or is running. If he runs, the dogs bark and squeal, as if they are being beaten; and if he stands, then they bark as if at a person and howl.

During this hunt I ran through the forest for a long time, but not once did I manage to cross the path of the boar. Finally I heard the prolonged barking and howling of hound dogs and ran to that place. I was already close to the wild boar. I could already hear more frequent crackling sounds. It was a boar with dogs tossing and turning. But you could hear from the barking that they did not take him, but only circled around him. Suddenly I heard something rustling from behind, and I saw Bulka. He apparently lost the hounds in the forest and got confused, and now he heard barking and, just like me, he rolled in that direction as best he could. He ran across the clearing, through the tall grass, and all I could see from him was his black head and his tongue bitten between his white teeth. I called out to him, but he did not look back, overtook me and disappeared into the thicket. I ran after him, but the further I walked, the more dense the forest became. Twigs knocked my hat off, hit me in the face, thorn needles clung to my dress. I was already close to barking, but I couldn’t see anything.

Suddenly I heard the dogs barking louder; something crackled loudly, and the boar began to puff and wheeze. I thought that now Bulka had gotten to him and was messing with him. With all my strength I ran through the thicket to that place.

In the deepest thicket I saw a motley hound dog. She barked and howled in one place, and three steps away from her something was fussing and turning black.

When I moved closer, I examined the boar and heard Bulka squeal piercingly. The boar grunted and leaned towards the hound, the hound tucked its tail and jumped away. I could see the side of the boar and its head. I aimed at the side and fired. I saw that I got it. The boar grunted and rattled away from me more often. The dogs squealed and barked after him, and I rushed after them more often. Suddenly, almost under my feet, I saw and heard something. It was Bulka. He lay on his side and screamed. There was a pool of blood underneath him. I thought: the dog is missing; but I had no time for him now, I pressed on.

Soon I saw a wild boar. The dogs grabbed him from behind, and he turned to one side or the other. When the boar saw me, he poked his head towards me. Another time I shot almost point-blank, so that the bristles on the boar caught fire, and the boar wheezed, staggered, and the whole carcass slammed heavily to the ground.

When I approached, the boar was already dead, and only here and there it swelled and twitched. But the dogs, bristling, some tore at his belly and legs, while others lapped up the blood from the wound.

Then I remembered about Bulka and went to look for him. He crawled towards me and moaned. I walked up to him, sat down and looked at his wound. His stomach was torn open, and a whole lump of intestines from his stomach was dragging along the dry leaves. When my comrades came to me, we set Bulka’s intestines and sewed up his stomach. While they were stitching up my stomach and piercing the skin, he kept licking my hands.

The boar was tied to the horse's tail to take it out of the forest, and Bulka was placed on the horse and so they brought him home. Bulka was ill for six weeks and recovered.

MILTON AND BULKA

I got myself a pointing dog for pheasants. This dog's name was Milton; she was tall, thin, speckled gray, with long jowls [Jowls, thick jowls, drooping lips on a dog] and ears, and very strong and intelligent. They didn’t fight with Bulka. Not a single dog ever snapped at Bulka. Sometimes he would just show his teeth, and the dogs would tuck their tails and move away. Once I went with Milton to buy pheasants. Suddenly Bulka ran after me into the forest. I wanted to drive him away, but I couldn’t. And it was a long way to go home to take him. I thought that he would not disturb me, and moved on; but as soon as Milton smelled a pheasant in the grass and began to look, Bulka rushed forward and began poking around in all directions. He tried before Milton to raise a pheasant. He heard something in the grass, jumped and spun; but his instincts were bad, and he could not find the trail alone, but looked at Milton and ran to where Milton was going. As soon as Milton sets off on the trail, Bulka runs ahead. I recalled Bulka, beat him, but could not do anything with him. As soon as Milton began to search, he rushed forward and interfered with him. I wanted to go home because I thought that my hunt was ruined, but Milton came up with a better idea than me how to deceive Bulka. This is what he did: as soon as Bulka runs ahead of him, Milton will leave the trail, turn in the other direction and pretend that he is looking. Bulka will rush to where Milton pointed, and Milton will look back at me, wave his tail and follow the real trail again. Bulka again runs to Milton, runs ahead, and again Milton will deliberately take ten steps to the side, deceive Bulka and again lead me straight. So throughout the hunt he deceived Bulka and did not let him ruin things.

BULKA AND THE WOLF

When I left the Caucasus, there was still a war there, and it was dangerous to travel at night without an escort [Convoy - here: security].

I wanted to leave as early as possible in the morning and for this I did not go to bed.

My friend came to see me off, and we sat all evening and night on the street of the village in front of my hut.

It was a month-long night with fog, and it was so light that you could read, although the month was not visible.

In the middle of the night, we suddenly heard a pig squeaking in the yard across the street. One of us shouted:

- This is a wolf strangling a piglet!

I ran to my hut, grabbed a loaded gun and ran out into the street. Everyone stood at the gate of the yard where the pig was squeaking and shouted to me: “Come here!”

Milton rushed after me - right, he thought that I was going hunting with a gun, and Bulka raised his short ears and darted from side to side, as if he was asking who he was being told to grab onto. When I ran up to the fence, I saw that from that side of the yard, an animal was running straight towards me. It was a wolf. He ran up to the fence and jumped on it. I moved away from him and prepared my gun. As soon as the wolf jumped from the fence to my side, I took it almost point-blank and pulled the trigger; but the gun went "chick" and didn't fire. The wolf didn't stop and ran across the street. Milton and Bulka ran after him. Milton was close to the wolf, but apparently was afraid to grab him; and Bulka, no matter how in a hurry on his short legs, could not keep up. We ran as hard as we could after the wolf, but both the wolf and the dogs disappeared from our sight. Only at the ditch at the corner of the village we heard barking, squealing and saw through the month-long fog that dust had risen and that the dogs were fiddling with the wolf. When we ran to the ditch, the wolf was no longer there, and both dogs returned to us with their tails raised and angry faces. Bulka growled and pushed me with his head - he obviously wanted to tell me something, but couldn’t.

We examined the dogs and found that Bulka had a small wound on her head. He apparently caught up with the wolf in front of the ditch, but did not have time to capture it, and the wolf snapped and ran away. The wound was small, so there was nothing dangerous.

We went back to the hut, sat and talked about what happened. I was annoyed that my gun had stopped short, and I kept thinking about how the wolf would have remained right there on the spot if it had fired. My friend was surprised that a wolf could get into the yard. The old Cossack said that there was nothing surprising here, that it was not a wolf, but that it was a witch and that she had bewitched my gun. So we sat and talked. Suddenly the dogs rushed, and we saw the same wolf again in the middle of the street in front of us; but this time he ran so quickly from our scream that the dogs could not catch up with him.

After this, the old Cossack was completely convinced that it was not a wolf, but a witch; and I thought that it was not a mad wolf, because I had never seen or heard of a wolf, after being driven away, returning again to the people.

Just in case, I sprinkled gunpowder on Bulke’s wound and lit it. The gunpowder flared up and burned the sore spot.

I burned the wound with gunpowder to burn out the mad saliva if it had not yet entered the blood. If drool got in and entered the blood, then I knew that it would spread through the blood throughout the body, and then it could no longer be cured.

WHAT HAPPENED TO BULKA IN PYATIGORSK

From the village I did not go directly to Russia, but first to Pyatigorsk and stayed there for two months. I gave Milton to the Cossack hunter, and took Bulka with me to Pyatigorsk.

Pyatigorsk is so called because it stands on Mount Beshtau. And Besh in Tatar means five, tau means mountain. Hot sulfur water flows from this mountain. This water is hot, like boiling water, and there is always steam above the place where the water comes from the mountain, like above a samovar. The whole place where the city stands is very cheerful. Hot springs flow from the mountains, and the Podkumok river flows under the mountain. There are forests along the mountain, fields all around, and in the distance you can always see the large Caucasus Mountains. On these mountains the snow never melts and they are always white as sugar. One big Mount Elbrus, like a sugar white loaf, is visible from everywhere when the weather is clear. People come to the hot springs for treatment, and gazebos and canopies are built over the springs, and gardens and paths are laid out all around. In the morning, music plays and people drink water or swim and walk.

The city itself stands on a mountain, and under the mountain there is a settlement. I lived in this settlement in a small house. The house stood in the courtyard, and in front of the windows there was a garden, and in the garden there were the owner’s bees - not in logs, as in Russia, but in round baskets. The bees there are so peaceful that I always sat with Bulka in this garden between the hives in the morning.

Bulka walked among the hives, marveled at the bees, smelled them, listened to them hum, but walked so carefully around them that he did not disturb them, and they did not touch him.

One morning I returned home from the waters and sat down to drink coffee in the front garden. Bulka began scratching behind his ears and rattling his collar. The noise disturbed the bees, and I took off Bulka’s collar. A little later I heard a strange and terrible noise coming from the city from the mountain. Dogs barked, howled, squealed, people screamed, and this noise descended from the mountain and came closer and closer to our settlement. Bulka stopped itching, laid his wide head with white teeth between his front white paws, laid his tongue as he needed it, and lay quietly next to me. When he heard the noise, he seemed to understand what it was, pricked up his ears, bared his teeth, jumped up and began to growl. The noise was getting closer. It was as if dogs from all over the city were howling, squealing and barking. I went out to the gate to look, and the owner of my house came up too. I asked:

- What it is?

She said:

- These are the convicts from the prison who go and beat the dogs. There were a lot of dogs, and the city authorities ordered to beat all the dogs in the city.

- How, will they kill Bulka if she gets caught?

- No, they don’t tell you to beat them with collars.

At the same time, as I was saying, the convicts approached our yard.

Soldiers walked in front, and behind were four convicts in chains. Two convicts had long iron hooks in their hands and two had clubs. In front of our gate, one convict hooked a yard dog with a hook, pulled it into the middle of the street, and another convict began to beat it with a club. The little dog squealed terribly, and the convicts shouted something and laughed. The kolodnik with a hook turned the little dog over, and when he saw that it was dead, he took out the hook and began to look around to see if there was another dog.

At this time, Bulka rushed headlong at this convict, as he rushed at the bear. I remembered that he was without a collar and shouted:

- Bulka, go back! - and shouted to the convicts not to beat Bulka.

But the convict saw Bulka, laughed and deftly hit Bulka with his hook and caught him in the thigh. Bulka rushed away, but the convict pulled him towards him and shouted to the other:

- Hit!

Another swung a club, and Bulka would have been killed, but he rushed, the skin broke through his thigh, and he, with his tail between his legs, with a red wound on his leg, rushed headlong into the gate, into the house, and hid under my bed.

He was saved by the fact that his skin broke through in the place where the hook was.

THE END OF BULL AND MILTON

Bulka and Milton ended at the same time. The old Cossack did not know how to handle Milton. Instead of taking him with him only for poultry, he began to take him after wild boars. And in the same autumn, the cleaver [The cleaver is a two-year-old boar with a sharp, not curved fang. (Note by L.N. Tolstoy)] the boar tore him open. No one knew how to sew it up, and Milton died. Bulka also did not live long after he escaped from the convicts. Soon after his rescue from the convicts, he began to get bored and began to lick everything he came across. He licked my hands, but not like he used to caress me. He licked for a long time and pressed his tongue hard, and then began to grab it with his teeth. Apparently he needed to bite his hand, but he didn’t want to. I didn't give him my hand. Then he began to lick my boot, the table leg and then bite the boot or table leg. This lasted two days, and on the third day he disappeared, and no one saw or heard of him.

It was impossible to steal him, and he could not leave me, and this happened to him six weeks after he was bitten by a wolf. Therefore, the wolf was definitely mad. Bulka got angry and left. What happened to him was what is called in hunting - a stichka. They say that rabies consists of convulsions in the throat of a rabid animal. Mad animals want to drink but cannot, because water makes the cramps worse.

Then they lose their temper from pain and thirst and begin to bite. That’s right, Bulka started having these convulsions when he started licking and then biting my hand and the table leg.

I drove everywhere around the district and asked about Bulka, but could not find out where he had gone or how he died. If he ran and bit, like mad dogs do, then I would have heard about him. Oh, that’s right, he ran somewhere into the wilderness and died there alone. Hunters say that when a smart dog gets into trouble, it runs into the fields or forests and there looks for the grass it needs, falls out in the dew and heals itself. Apparently, Bulka could not recover. He did not return and disappeared.

An officer's story

I had a little face... Her name was Bulka. She was all black, only the tips of her front paws were white.

In all faces, the lower jaw is longer than the upper and the upper teeth extend beyond the lower ones; but Bulka’s lower jaw protruded forward so much that a finger could be placed between the lower and upper teeth. Bulka's face was wide; the eyes are large, black and shiny; and white teeth and fangs always stuck out. He looked like a blackamoor. Bulka was quiet and did not bite, but he was very strong and tenacious. When he would cling to something, he would clench his teeth and hang like a rag, and, like a tick, he could not be torn off.

Once they let him attack a bear, and he grabbed the bear’s ear and hung like a leech. The bear beat him with his paws, pressed him to himself, threw him from side to side, but could not tear him away and fell on his head to crush Bulka; but Bulka held on to it until they poured cold water on him.

I took him as a puppy and raised him myself. When I went to serve in the Caucasus, I didn’t want to take him and left him quietly, and ordered him to be locked up. At the first station, I was about to board another transfer station, when suddenly I saw something black and shiny rolling along the road. It was Bulka in his copper collar. He flew at full speed towards the station. He rushed towards me, licked my hand and stretched out in the shadows under the cart. His tongue stuck out the entire palm of his hand. He then pulled it back, swallowing drool, then again stuck it out to the whole palm. He was in a hurry, did not have time to breathe, his sides were jumping. He turned from side to side and tapped his tail on the ground.

I found out later that after me he broke through the frame and jumped out of the window and, right in my wake, galloped along the road and rode like that for twenty miles in the heat.

Year of writing: 1862

Genre: story

Plot:

Bulka is the name of the dog that the narrator adores so much. The dog is strong, but kind and never bites people. At the same time, Bulka loves hunting and can defeat many animals.

One day the dog grabbed onto the bear, and he could not tear himself away from her; only after dousing Bulka with cold water, they were able to unhook him. Bulka is brave and is always the first to rush at the animal, so one day the boar cut the dog’s stomach, but it was stitched up and the dog recovered. At the end of the story, Bulka also dies from an animal, since the wolf that she bit while hunting apparently had rabies and the dog eventually got sick and then ran away.

As hunters say, smart dogs run away to die, but not to upset the owner. The narrator also talks about how Bulka, when she stayed at home and he went hunting with other dogs, eventually broke out and joined the hunt, and once ran after him 20 miles to the station, when he was leaving for the Caucasus. The story describes the good relationship between the owner and the dog, and tells about the dog’s devotion.

Picture or drawing of Bulka

Other retellings and reviews for the reader's diary

- Summary of Lomonosov Ode on the Day of Accession to the All-Russian Throne

In the middle of the 13th century, M.V. Lomonosov created a laudatory ode dedicated to the arrival of the monarch Elizabeth to the throne. The majestic work was dedicated to the six-year anniversary of Elizabeth Petrovna’s accession to the throne.

- Summary Garshin The Legend of Proud Haggai

Fate does not tolerate dictators and cruel people; it likes more loyal and benevolent people. This is yet another proof that good still triumphs over evil. Once upon a time there lived in a certain state a ruler

- Aksakov

Aksakov Sergei Timofeevich was born in Ufa on October 1, 1791. From 1801 to 1807 he studied at Kazan University. It was there that he began working on a handwritten student magazine. The first sentimental poems... Thus a new writer was born.

- Summary of Chekhov The Seagull

The play takes place on the estate of Peter Nikolaevich Sorin, his actress sister, Irina Nikolaevna Arkadina, came to visit him, and the novelist Boris Trigorin also came with her, the latter was not yet forty, but he was already quite famous

- Summary of Gorky Varvara

Silence and the usual bourgeois lifestyle The county town is disrupted by the appearance of engineers from the capital. It is planned to build a railway track in the town.

Bulka (Officer's Stories)

Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy

Tolstoy Lev Nikolaevich

Bulka (Officer's Stories)

Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy

(Officer's stories)

I had a face. Her name was Bulka. She was all black, only the tips of her front paws were white.

In all faces, the lower jaw is longer than the upper, and the upper teeth extend beyond the lower ones; but Bulka’s lower jaw protruded forward so much that a finger could be placed between the lower and upper teeth. Bulka's face was wide, her eyes were large, black and shiny; and white teeth and fangs always stuck out. He looked like a blackamoor. Bulka was quiet and did not bite, but he was very strong and tenacious. When he would cling to something, he would clench his teeth and hang like a rag, and, like a tick, he could not be torn off.

Once they let him attack a bear, and he grabbed the bear’s ear and hung like a leech. The bear beat him with his paws, pressed him to himself, threw him from side to side, but could not tear him away and fell on his head to crush Bulka; but Bulka held on to it until they poured cold water on him.

I took him as a puppy and raised him myself. When I went to serve in the Caucasus, I didn’t want to take him and left him quietly, and ordered him to be locked up. At the first station, I wanted to board another crossbar [Pereknaya - a carriage drawn by horses, which changed at postal stations; “were traveling on crossroads” in Russia before the construction of railways], when suddenly I saw something black and shiny rolling along the road. It was Bulka in his copper collar. He flew at full speed towards the station. He rushed towards me, licked my hand and stretched out in the shadows under the cart.

His tongue stuck out the entire palm of his hand. He then pulled it back, swallowing drool, then again stuck it out to the whole palm. He was in a hurry, did not have time to breathe, his sides were jumping. He turned from side to side and tapped his tail on the ground.

I found out later that after me he broke through the frame and jumped out of the window and, right in my wake, galloped along the road and rode like that for twenty miles in the heat.

BULKA AND BOAR

Once in the Caucasus we went boar hunting, and Bulka came running with me. As soon as the hounds started driving, Bulka rushed towards their voice and disappeared into the forest. This was in November: wild boars and pigs are very fat then.

In the Caucasus, in the forests where wild boars live, there are many delicious fruits: wild grapes, cones, apples, pears, blackberries, acorns, blackthorns. And when all these fruits are ripe and touched by frost, the wild boars eat up and grow fat.

At that time, the boar is so fat that it cannot run under the dogs for long. When they have been chasing him for two hours, he gets stuck in a thicket and stops. Then the hunters run to the place where he stands and shoot. You can tell by the barking of dogs whether a boar has stopped or is running. If he runs, the dogs bark and squeal, as if they are being beaten; and if he stands, then they bark as if at a person and howl.

During this hunt I ran through the forest for a long time, but not once did I manage to cross the path of the boar. Finally I heard the prolonged barking and howling of hound dogs and ran to that place. I was already close to the wild boar. I could already hear more frequent crackling sounds. It was a boar with dogs tossing and turning. But you could hear from the barking that they did not take him, but only circled around him. Suddenly I heard something rustling from behind, and I saw Bulka. He apparently lost the hounds in the forest and got confused, and now he heard barking and, just like me, he rolled in that direction as best he could. He ran across the clearing, through the tall grass, and all I could see from him was his black head and his tongue bitten between his white teeth. I called out to him, but he did not look back, overtook me and disappeared into the thicket. I ran after him, but the further I walked, the more dense the forest became. Twigs knocked my hat off, hit me in the face, thorn needles clung to my dress. I was already close to barking, but I couldn’t see anything.

Suddenly I heard the dogs barking louder; something crackled loudly, and the boar began to puff and wheeze. I thought that now Bulka had gotten to him and was messing with him. With all my strength I ran through the thicket to that place.

In the deepest thicket I saw a motley hound dog. She barked and howled in one place, and three steps away from her something was fussing and turning black.

When I moved closer, I examined the boar and heard Bulka squeal piercingly. The boar grunted and leaned towards the hound, the hound tucked its tail and jumped away. I could see the side of the boar and its head. I aimed at the side and fired. I saw that I got it. The boar grunted and rattled away from me more often. The dogs squealed and barked after him, and I rushed after them more often. Suddenly, almost under my feet, I saw and heard something. It was Bulka. He lay on his side and screamed. There was a pool of blood underneath him. I thought: the dog is missing; but I had no time for him now, I pressed on.

Soon I saw a wild boar. The dogs grabbed him from behind, and he turned to one side or the other. When the boar saw me, he poked his head towards me. Another time I shot almost point-blank, so that the bristles on the boar caught fire, and the boar wheezed, staggered, and the whole carcass slammed heavily to the ground.

When I approached, the boar was already dead, and only here and there it swelled and twitched. But the dogs, bristling, some tore at his belly and legs, while others lapped up the blood from the wound.

Then I remembered about Bulka and went to look for him. He crawled towards me and moaned. I walked up to him, sat down and looked at his wound. His stomach was torn open, and a whole lump of intestines from his stomach was dragging along the dry leaves. When my comrades came to me, we set Bulka’s intestines and sewed up his stomach. While they were stitching up my stomach and piercing the skin, he kept licking my hands.

The boar was tied to the horse's tail to take it out of the forest, and Bulka was placed on the horse and so they brought him home. Bulka was ill for six weeks and recovered.

MILTON AND BULKA

I got myself a pointing dog for pheasants. This dog's name was Milton; she was tall, thin, speckled gray, with long jowls [Jowls, thick jowls, drooping lips on a dog] and ears, and very strong and intelligent. They didn’t fight with Bulka. Not a single dog ever snapped at Bulka. Sometimes he would just show his teeth, and the dogs would tuck their tails and move away. Once I went with Milton to buy pheasants. Suddenly Bulka ran after me into the forest. I wanted to drive him away, but I couldn’t. And it was a long way to go home to take him. I thought that he would not disturb me, and moved on; but as soon as Milton smelled a pheasant in the grass and began to look, Bulka rushed forward and began poking around in all directions. He tried before Milton to raise a pheasant. He heard something in the grass, jumped and spun; but his instincts were bad, and he could not find the trail alone, but looked at Milton and ran to where Milton was going. As soon as Milton sets off on the trail, Bulka runs ahead. I recalled Bulka, beat him, but could not do anything with him. As soon as Milton began to search, he rushed forward and interfered with him. I wanted to go home because I thought that my hunt was ruined, but Milton came up with a better idea than me how to deceive Bulka. This is what he did: as soon as Bulka runs ahead of him, Milton will leave the trail, turn in the other direction and pretend that he is looking. Bulka will rush to where Milton pointed, and Milton will look back at me, wave his tail and follow the real trail again. Bulka again runs to Milton, runs ahead, and again Milton will deliberately take ten steps to the side, deceive Bulka and again lead me straight. So throughout the hunt he deceived Bulka and did not let him ruin things.

BULKA AND THE WOLF

When I left the Caucasus, there was still a war there, and it was dangerous to travel at night without an escort [Convoy - here: security].

I wanted to leave as early as possible in the morning and for this I did not go to bed.

My friend came to see me off, and we sat all evening and night on the street of the village in front of my hut.

It was a month-long night with fog, and it was so light that you could read, although the month was not visible.

In the middle of the night, we suddenly heard a pig squeaking in the yard across the street. One of us shouted:

It's a wolf strangling a piglet!

I ran to my hut, grabbed a loaded gun and ran out into the street. Everyone stood at the gate of the yard where the pig was squeaking and shouted to me: “Come here!”

Milton rushed after me - right, he thought that I was going hunting with a gun, and Bulka raised his short ears and darted from side to side, as if he was asking who he was being told to grab onto. When I ran up to the fence, I saw that from that side of the yard, an animal was running straight towards me. It was a wolf. He ran up to the fence and jumped on it. I moved away from him and prepared my gun. As soon as the wolf jumped from the fence to my side, I took it almost point-blank and pulled the trigger; but the gun went "chick" and didn't fire. The wolf didn't stop and ran across the street. Milton and Bulka ran after him. Milton was close to the wolf, but apparently was afraid to grab him; and Bulka, no matter how in a hurry on his short legs, could not keep up. We ran as hard as we could after the wolf, but both the wolf and the dogs disappeared from our sight. Only at the ditch at the corner of the village we heard barking, squealing and saw through the month-long fog that dust had risen and that the dogs were fiddling with the wolf. When we ran to the ditch, the wolf was no longer there, and both dogs returned to us with their tails raised and angry faces. Bulka growled and pushed me with his head - he obviously wanted to tell me something, but couldn’t.

We examined the dogs and found that Bulka had a small wound on her head. He apparently caught up with the wolf in front of the ditch, but did not have time to capture it, and the wolf snapped and ran away. The wound was small, so there was nothing dangerous.

We went back to the hut, sat and talked about what happened. I was annoyed that my gun had stopped short, and I kept thinking about how the wolf would have remained right there on the spot if it had fired. My friend was surprised that a wolf could get into the yard. The old Cossack said that there was nothing surprising here, that it was not a wolf, but that it was a witch and that she had bewitched my gun. So we sat and talked. Suddenly the dogs rushed, and we saw the same wolf again in the middle of the street in front of us; but this time he ran so quickly from our scream that the dogs could not catch up with him.

After this, the old Cossack was completely convinced that it was not a wolf, but a witch; and I thought that it was not a mad wolf, because I had never seen or heard of a wolf, after being driven away, returning again to the people.

Just in case, I sprinkled gunpowder on Bulke’s wound and lit it. The gunpowder flared up and burned the sore spot.

I burned the wound with gunpowder to burn out the mad saliva if it had not yet entered the blood. If drool got in and entered the blood, then I knew that it would spread through the blood throughout the body, and then it could no longer be cured.

WHAT HAPPENED TO BULKA IN PYATIGORSK

From the village I did not go directly to Russia, but first to Pyatigorsk and stayed there for two months. I gave Milton to the Cossack hunter, and took Bulka with me to Pyatigorsk.

Pyatigorsk is so called because it stands on Mount Beshtau. And Besh in Tatar means five, tau means mountain. Hot sulfur water flows from this mountain. This water is hot, like boiling water, and there is always steam above the place where the water comes from the mountain, like above a samovar. The whole place where the city stands is very cheerful. Hot springs flow from the mountains, and the Podkumok river flows under the mountain. There are forests along the mountain, fields all around, and in the distance you can always see the large Caucasus Mountains. On these mountains the snow never melts and they are always white as sugar. One big Mount Elbrus, like a sugar white loaf, is visible from everywhere when the weather is clear. People come to the hot springs for treatment, and gazebos and canopies are built over the springs, and gardens and paths are laid out all around. In the morning, music plays and people drink water or swim and walk.

The city itself stands on a mountain, and under the mountain there is a settlement. I lived in this settlement in a small house. The house stood in the courtyard, and in front of the windows there was a garden, and in the garden there were the owner’s bees - not in logs, as in Russia, but in round baskets. The bees there are so peaceful that I always sat with Bulka in this garden between the hives in the morning.

Bulka walked among the hives, marveled at the bees, smelled them, listened to them hum, but walked so carefully around them that he did not disturb them, and they did not touch him.

One morning I returned home from the waters and sat down to drink coffee in the front garden. Bulka began scratching behind his ears and rattling his collar. The noise disturbed the bees, and I took off Bulka’s collar. A little later I heard a strange and terrible noise coming from the city from the mountain. Dogs barked, howled, squealed, people screamed, and this noise descended from the mountain and came closer and closer to our settlement. Bulka stopped itching, laid his wide head with white teeth between his front white paws, laid his tongue as he needed it, and lay quietly next to me. When he heard the noise, he seemed to understand what it was, pricked up his ears, bared his teeth, jumped up and began to growl. The noise was getting closer. It was as if dogs from all over the city were howling, squealing and barking. I went out to the gate to look, and the owner of my house came up too. I asked:

What it is?

She said:

These are convicts from the prison walking around beating dogs. There were a lot of dogs, and the city authorities ordered to beat all the dogs in the city.

How, and will Bulka be killed if he gets caught?

No, people with collars are not ordered to beat.

At the same time, as I was saying, the convicts approached our yard.

Soldiers walked in front, and behind were four convicts in chains. Two convicts had long iron hooks in their hands and two had clubs. In front of our gate, one convict hooked a yard dog with a hook, pulled it into the middle of the street, and another convict began to beat it with a club. The little dog squealed terribly, and the convicts shouted something and laughed. The kolodnik with a hook turned the little dog over, and when he saw that it was dead, he took out the hook and began to look around to see if there was another dog.

At this time, Bulka rushed headlong at this convict, as he rushed at the bear. I remembered that he was without a collar and shouted:

Bulka, go back! - and shouted to the convicts not to beat Bulka.

But the convict saw Bulka, laughed and deftly hit Bulka with his hook and caught him in the thigh. Bulka rushed away, but the convict pulled him towards him and shouted to the other:

Another swung a club, and Bulka would have been killed, but he rushed, the skin broke through his thigh, and he, with his tail between his legs, with a red wound on his leg, rushed headlong into the gate, into the house, and hid under my bed.