Military Observer. What is the Tarutino military maneuver Kutuzov Battle of Tarutino 1812 war and peace

There are small moments in history, seemingly insignificant at first glance, sometimes even curious, which in the future have a significant impact on the course of further events. These include the Tarutino battle, or rather not even a battle, but a clash that took place on October 18, 1812. near the village of Tarutino, the Russian army with the vanguard of the French army, where M.N. retreated. Kutuzov, leaving Moscow. This clash had more of a moral significance than a military one - the French vanguard under the leadership of Marshal Murat was not defeated, but it could have been.

In all sources, this episode is interpreted as the Tarutino battle, but as I said above, it is more like a collision with big blunders, where the principle “it was smooth on paper, but they forgot about the ravines!” was justified.

Kutuzov's main strategic success at Borodino was that the large French losses provided time for replenishment, supplies, and reorganization of the Russian army, which the commander-in-chief then launched into a formidable counter-offensive against Napoleon.

Napoleon did not attack the Russian army during its retreat from Borodino to Moscow, not because he considered the war to be won, but because he feared a second Borodino, after which he would have had to ask for a shameful peace.

While in Moscow and soberly assessing the situation, Napoleon sent his representatives to Alexander 1 and M.I. Kutuzov with a proposal to make peace. But he was refused. And realizing that Moscow was a trap for him, he gave the order to retreat.

And at this time, in the Tarutino camp, the Russian army received reinforcements and increased its strength to 120 thousand people. In 1834, a monument was erected in Tarutino with the inscription: “In this place, the Russian army, led by Field Marshal Kutuzov, saved Russia and Europe».

Although the Cossacks initially misled the French vanguard, which was following on the heels of the Russian army, Murat’s corps still discovered Kutuzov’s camp and stopped not far from Tarutino, observing the Russian army. The strength of the French corps was 26,540 people with artillery of 197 guns. Only the forest separated the Russian camp from the French positions.

It was a strange neighborhood. Enemy troops stood for two weeks without fighting. Moreover, according to the testimony of General A.P. Ermolova: “ Gentlemen generals and officers gathered at the front posts with expressions of politeness, which was the reason for many to conclude that there was a truce.”(Napoleon was waiting for an answer to peace - V.K.). By this time, the partisans reported that the French had no reinforcements at a distance from their position to Moscow. This caused the plan to encircle and destroy the French corps, but..., as I said above, the human factor is to blame for everything.

Murat apparently received information about the impending Russian attack the day before it began. The French were in full combat readiness all night, but the attack did not occur due to the fact that General Ermolov was at their dinner party. The next day, Murat ordered the withdrawal of artillery and convoys. But the adjutant who delivered the order to the chief of artillery found him sleeping and, unaware of the urgency, decided to wait until the morning. As a result, the French were unprepared to repel the attack.

In turn, mistakes were made on the Russian side. They were let down by the lack of cooperation among the detachments of Bennigsen, Miloradovich and Orlov-Denisov, allocated to attack the French. Only the Cossacks of Orlov-Denisov, who reached their initial positions in time, attacked the French camp, who took to their heels, and the Cossacks began to “shmon” their camp. This allowed Murat to stop the fleeing French and organize counterattacks, thereby saving his corps.

The goal of the Tarutino battle was not fully achieved, but its result was extremely successful: in no other battle during that war were so many guns captured (38).

But the significance of this battle lay not only in the success and effectiveness of the military component, this battle contributed to the rise of the spirit of the Russian army and marked a new stage of the Patriotic War - the transition to active offensive actions, which the army and the entire Russian society had dreamed of for so long. This battle showed that the Russians could beat the French, just as the Battle of Moscow in 1941 showed that Hitler’s army could be crushed.

The day after the battle, M.I. Kutuzov wrote to his wife: “ It was no wonder to break them. But it was necessary to destroy it cheaply for us... For the first time, the French lost so many guns, and for the first time they ran like hares...”

The next one will be on October 22-23, 1812, the battle of Maloyaroslavets, which will become Borodino -2 for the French, but with a negative sign.

The battle near Tarutino on October 18, 1812 was the beginning of the countdown to the victory of the Russian people in the Patriotic War of 1812. On this day, October 18, 1962, in honor of the 150th anniversary of the Victory, the Battle of Borodino Panorama Museum was opened in Moscow - an eternal monument to those days.

VADIM KULINCHENKO, retired captain 1st rank, publicist

“We didn’t know how to take Murat alive in the morning”: Tarutino battle

When it became clear to Kutuzov that it was impossible to defend Moscow with available forces, he decided to break away from the enemy and take a position that would cover Russian supply bases in Tula and Kaluga and threaten the operational line of Napoleonic troops in order to gain time and create conditions for launching a counteroffensive . It was this maneuver that went down in the history of the War of 1812 as the Tarutino maneuver. So, on the evening of September 5 (17), the commander-in-chief gave the order to the retreating Russian army to turn off the Ryazan road and go to Podolsk. None of the corps commanders knew where or why the army was turning, and only by the evening of the next day the army reached the Tula road near Podolsk. Next, Russian troops went along the old Kaluga road south to Krasnaya Pakhra, after passing which they stopped at the village of Tarutino.

Military historian and adjutant of Kutuzov A. Mikhailovsky-Danilevsky described in detail the advantages that the Russian army received from these movements: “Having established a firm foot on the Kaluga road, Prince Kutuzov had the opportunity:

1) cover the midday provinces, which were abundant in supplies;

2) threaten the route of enemy actions from Moscow through Mozhaisk, Vyazma and Smolensk;

3) to cross the French communications stretched over an excessive area in detachments and

4) in the event of Napoleon’s retreat to Smolensk, warn him along the shortest road.”

This march-maneuver, which was considered brilliant by both supporters and opponents of Kutuzov, ended successfully. Indeed, it allowed Russian troops to protect from the enemy both food reserves in Kaluga, arms factories in Tula, and foundries in Bryansk. Also, Napoleon's path to the fertile Ukrainian provinces was cut off. And it was precisely this location that deprived the French of the opportunity to implement the so-called “autumn plan” for a campaign against St. Petersburg.

French General A. Jomini admitted that in the history of wars since ancient times, “the retreat that the Russian army made in 1812 from the Neman to Moscow... without allowing itself to be upset or partially defeated by such an enemy as Napoleon... of course, should be placed above all others” not so much in terms of the “strategic talents” of the generals, but “in relation to the amazing confidence, steadfastness and firmness of the troops.”

Separately, it is necessary to point out that the Tarutino maneuver went unnoticed by the French. Thus, Kutuzov wrote in a report to the emperor: “The army, making a flank movement, for the sake of secrecy in this direction, confused the enemy on every march. Heading herself to a certain point, she disguised herself with false movements of light troops, making demonstrations first to Kolomna, then to Serpukhov, after which the enemy followed in large parties.”

The reaction of the French themselves was described in their memoirs by the German doctor Murat G. von Roos: “We drove off, accompanied by smoke that was driving towards us from the direction of the city. The sun shone through the smoke, turning all visible objects yellow. The Cossacks were very close in front of us, but that day we did not even exchange pistol shots... The next day, September 16, we moved further along the road leading to Vladimir and Kazan. We saw our opponents only in the evening, when we approached the wooden town of Bogorodsk, which stood to the right of the road.” After this, the French moved for another day in the direction in which the Cossacks had disappeared. And only on the third day, “in the early morning,” Roos wrote, “I paid a visit to my commander, Colonel von Mielkau. He greeted me with the words: “We have lost the enemy and every trace of him; we have to stay here and wait for new orders.”

In fact, Murat, moving along the Ryazan road, missed the flank movement Russian troops, and when on September 10 (22) the Cossacks dispersed along with the fog, he discovered an empty road in front of him. The mood of the French troops at this time was quite colorfully described by Marshal B. de Castellant: “Our vanguard is twelve miles away. The Neapolitan king, standing in the mud in his yellow boots, with his Gascon accent, spoke to the officer sent by the emperor in the following terms: “Tell the emperor that I carried the vanguard of the French army beyond Moscow with honor, but I’m tired, tired of all this, do you hear Do you? I want to go to Naples to take care of my subjects."

Kutuzov himself was very pleased with the implementation of his plan. In his next report to Emperor Alexander I, he noted: “I am still receiving information about the success of my false movement, for the enemy followed the Cossacks in parts (that is, the detachment left on the Ryazan road). This gives me the convenience that the army, having made a flank march of 18 versts on the Kaluga road tomorrow and sent strong parties to Mozhaiskaya, should greatly concern the enemy’s rear. In this way I hope that the enemy will seek to give me a battle, from which, in a favorable location, I expect equal successes, as at Borodino.”

After some time, as Roos wrote, the French “again found the Russians, who seemed to have sunk into the abyss from the moment when ... they saw them on the top of the hill near Bogorodsk. The bloody war fun began again; all types of weapons were put into action, cannon fire occurred every day, often from morning to evening...”

Thus, after withdrawing from Moscow, the Russian army by early October 1812 settled in a fortified camp near the village of Tarutino across the Nara River (southwest of Moscow). The soldiers received rest, and the army as a whole received the opportunity to replenish material and manpower.

At the beginning of October, the commander-in-chief sent an official report to Emperor Alexander I, in which he reported that he had brought 87,035 people with 622 guns to the camp. There is information that immediately after arriving in Tarutino, Kutuzov announced: “Now not a step back!”

In the Tarutino camp, the troops were officially renamed. From that time on, the 1st and 2nd Western Armies merged into the Main Army, commanded by M.I. Golenishchev-Kutuzov. The first days of the army's stay in the camp were accompanied by certain difficulties: there was a lack of food and ammunition, as well as organization. Radozhitsky wrote about the lack of provisions: “Approaching the devastated road, we ourselves began to suffer from poverty, especially our horses: there was no fodder at all, and the poor animals fed only on rotten straw from the roofs. I also had a small supply of oats from the Tarutino camp; Being the owner of the Figner artillery company, I saved oats a lot and only fed them to the horses. Day by day it became more painful; the serviceability of the artillery depended on the horses, and therefore I tried to preserve them by covering them with blankets; The gunners sometimes fed them with crackers.”

In the Tarutino camp, the conflict between M. Kutuzov and M. Barclay de Tolly, which had subsided for a while, escalated. In a letter to Alexander I, Kutuzov explained the surrender of Moscow by the poor condition of the troops after the loss of Smolensk, thus, in fact, placing all the blame on Barclay de Tolly. The latter understood perfectly well that the army was desolate after Borodin, and it was withdrawing from Smolensk in full battle order. Accordingly, Barclay de Tolly also remembered the fact that at the military council in Fili he advocated retreat without a fight, while criticizing the disposition proposed by Bennigsen. It is known that in the Battle of Borodino, Barclay de Tolly demonstrated unprecedented courage and personal bravery. Although this was noted by many, he was unable to shake off his reputation as a "German traitor". As a result, on October 4, Barclay de Tolly wrote a note to Kutuzov in which he asked “due to illness” to relieve him of his post. This request was granted, and the former commander of the 1st Western Army left the troops.

While in the Tarutino camp, Kutuzov took special care of the material component of the army. If there were problems for transporting the remaining supplies in Riga, Pskov, Tver, Kiev and Kaluga, he demanded active cooperation in this matter from the authorities of all nearby provinces, constantly receiving from them ammunition, bread, boots, sheepskin coats and even nails for horseshoes. About this, the field marshal wrote the following to the Kaluga and Tula governors: “I can’t find words with which I could express how great the benefit can come from if the donated provisions continuously reach the army and satisfy the needs for its non-stop food supply; and, on the contrary, I cannot, without great regret, explain that the slow delivery of food to the army is able to stop the movement of the army and completely stop the pursuit of the fleeing enemy.”

In addition to the official authorities, local residents also helped the Russian troops. Taken together, all the measures taken by Kutuzov led to the fact that by October 21, the Russian army already had more provisions than it needed.

At the same time, Napoleon, who occupied Moscow, found himself, as we have already said, in a very difficult situation - his troops could not fully provide themselves with the necessities in the city. In addition, the intensified guerrilla war interfered with the normal supply of the army. For foraging, the French had to send significant detachments, which did not often return without losses. At the same time, to facilitate the collection of provisions and the protection of communications, Napoleon was forced to maintain large military formations far beyond the borders of Moscow.

Indeed, taking advantage of these circumstances, Kutuzov refrained from active hostilities and resorted to a “small war with a big advantage” - guerrilla warfare. In particular, Russian troops even threatened the Moscow-Smolensk highway, along which the French received reinforcements and food.

Later, the additional advantage of Kutuzov’s position near the village of Tarutino became apparent. So, without waiting for peace from the Russian emperor, Napoleon, as already mentioned, considered the option of marching on St. Petersburg. But in addition to the mentioned reasons for abandoning such an idea (in particular, the approach of winter), it is necessary to mention the actual location of Kutuzov’s troops near Tarutino, that is, actually south of Moscow. Accordingly, if the French began a campaign against St. Petersburg, the Russian army would be in his rear.

In particular, Murat's vanguard had been stationed since mid-September, observing the Russian army, not far from their Tarutino camp on the Chernishna River, 90 kilometers from Moscow. This group consisted of the following units: Poniatowski's 5th Corps, two infantry and two cavalry divisions, all four cavalry corps of Emperor Napoleon. Her total number, according to army reports at the end of September, numbered 26,540 people (this data was given by the captain of the Guards Horse Artillery Chambray). At the same time, Chambray himself, taking into account the losses over the previous month, estimated the strength of the vanguard on the eve of the battle at 20,000 people.

It should be noted that the vanguard had strong artillery (197 guns). However, as Clausewitz pointed out, they “were rather a burden to the avant-garde than they could be useful to it.” The front and right flank of Murat's extended position were covered by the Nara and Chernishnaya rivers, the left flank went out into the open, where only a forest separated the French from the Russian positions.

For some time, both the Russian army and the French vanguard coexisted without military clashes. As General A. Ermolov pointed out, “Messrs. generals and officers gathered at forward posts with expressions of politeness, which was the reason for many to conclude that there was a truce.” Both sides remained in this situation for two weeks.

When the partisans reported that Murat did not have reinforcements closer than in Moscow in case of an attack, it was decided to attack the French, taking advantage of a successful disposition.

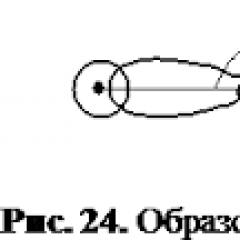

The attack plan was developed by cavalry general Bennigsen, chief of the General Staff of Kutuzov. First of all, it was decided to take advantage of the fact that a large forest approached the French left flank almost closely, and this made it possible to secretly approach their location.

According to the plan, the army was supposed to attack in two parts. The first (four infantry corps, one cavalry corps, ten Cossack regiments under the command of Adjutant General Count Orlov-Denisov), under the personal command of Bennigsen, was supposed to secretly bypass the French left flank through the forest. The other, under the command of Miloradovich, pinned down the other (right) flank of the French vanguard. At the same time, a separate detachment of Lieutenant General Dorokhov received the task of cutting off Murat’s escape route. Commander-in-Chief Kutuzov himself had to remain with the reserves in the camp and exercise general leadership.

Realizing the riskiness of his position, Murat also had information about the upcoming attack. Most likely, the training of Russian troops did not remain a secret to him. Therefore, the day before the battle, the French stood under arms all night in full readiness. But the expected attack did not come. As it turned out, the planned attack by Russian troops was a day late due to the absence of Chief of Staff Ermolov, who was at a dinner party at the time.

In fact, this circumstance played into Kutuzov’s hands. So, the next day, Murat issued an order to withdraw artillery and convoys. But his adjutant, having delivered the order to the chief of artillery, found him sleeping and, unaware of the urgency of the package, decided to wait until the morning. As a result, the French were absolutely unprepared to repel the attack. The moment for the battle turned out to be successful for the Russian army.

Preparations for the attack began with Bennigsen's columns, being careful, crossing the Nara River near Spassky. But again, another mistake affected the course of events. In particular, the night march and incorrect calculation of the encircling movement led to a slowdown, so the Russian troops did not have time to approach the enemy in a timely manner. Only the Cossack regiments of Orlov-Denisov reached the village of Dmitrovskoye behind the French left flank before dawn. Miloradovich on the French right flank also did not make active movements until dawn.

When dawn began (at this time the attack was planned to begin), Bennigsen’s infantry corps never showed up at the edge. In such a situation, not wanting to miss the surprise and opportunity, Orlov-Denisov decided to attack on his own. As a result, the French from General Sebastiani's corps managed to fire several shots in a hurry, but fled in disarray behind the Ryazanovsky ravine. After this, the Cossacks rushed to plunder the camp and Orlov-Denisov could not gather them for a long time. The French left flank was saved from complete defeat by Murat, who, having gathered those who fled, organized counterattacks and stopped the advance of the Cossacks.

One of the witnesses to this battle recalled: “King Murat immediately rushed to the attacked point and, with his presence of mind and courage, stopped the offensive that had begun. He rushed to all the bivouacs, collected all the horsemen he came across and, as soon as he managed to recruit such a squadron, he immediately rushed with them to the attack. Our cavalry owes its salvation precisely to these consistent and repeated attacks, which, having stopped the enemy, gave the troops time and the opportunity to look around, gather and go to the enemy.”

It was at this moment that one of Bennigsen’s buildings appeared at the edge of the forest near Teterinka, directly opposite the French battery. It was commanded by Lieutenant General K. Baggovut. An artillery firefight ensued. Baggovut, who had previously taken part in the Battle of Borodino, died in it. This event did not allow his corps to act more decisively. Bennigsen, also not prone to improvisation on the battlefield, did not dare to act with only part of his forces and gave the order to withdraw before the arrival of the rest of the troops, who continued to wander through the forest.

Murat successfully took advantage of this confusion of the Russian troops. Repelling the attacks of Orlov-Denisov’s Cossacks, he ordered the artillery convoys to retreat. Therefore, when the rest of Bennigsen’s corps finally appeared from the forest, the moment to defeat the French had already been missed.

Shell-shocked during this battle, Bennigsen was furious and wrote in a letter to his wife: “I can’t come to my senses! What could be the consequences of this wonderful, brilliant day if I had received support... Here, in front of the entire army, Kutuzov forbids sending even one person to help me, these are his words. General Miloradovich, who commanded the left wing, was eager to get closer to help me - Kutuzov forbids him... You can imagine how far from the battlefield our old man was! His cowardice already exceeds the limits permissible for cowards; he already gave under Borodin the greatest thing proof, that’s why he covered himself with contempt and became ridiculous in the eyes of the entire army... Can you imagine my position, that I need to quarrel with him every time it comes to taking one step against the enemy, and I need to listen to rudeness from this man!"

Indeed, as already indicated, Miloradovich’s troops were on the other flank. But in the midst of the battle they slowly moved along the old Kaluga road. Most likely, given the lateness of the bypass columns, Kutuzov ordered Miloradovich’s troops to stop. Assessing this decision, some researchers point out that, despite the retreat of the French, there remained significant chances of cutting off their individual parts.

Kutuzov himself, in turn. Even during the battle, he noted that “if we did not know how to take Murat alive in the morning and arrive at the place on time, then the pursuit would be useless. We can’t move away from the position.”

Having retreated with the main forces to Spas-Kupla, Murat strengthened the position with batteries and opened frontal fire on the Orlov-Denisov Cossacks who were pursuing him. In such conditions, the Russian regiments returned to their camp in the evening with songs and music.

Assessing the results of the Tarutino battle, it should be noted that the defeat of Murat did not work out not only because of mistakes in planning the attack, but also due to the inaccurate execution of the plans by Russian troops. As the historian M. Bogdanovich pointed out, with Russian side 5 thousand infantry and 7 thousand cavalry took part in this battle.

At the same time, some reluctance of Kutuzov to get involved in another battle with the French was also important. Most likely, the commander-in-chief of the Russian army considered unnecessary fighting, since time was already working in his favor. In addition, there was already information that Napoleon was preparing to withdraw from Moscow, so Kutuzov did not want to expose the troops to additional danger by withdrawing them from the camp. At the same time, the commander-in-chief was trying to solve one of his personal problems: to disable Bennigsen, who had been intriguing against him all the time. Accordingly, having appointed this general to command the troops, he did not give him full power, first of all, regarding the issue of possible reinforcements, as well as the occupation of positions at the end of the battle.

General A. Ermolov spoke quite critically about the results of the Tarutino battle: “The battle could have ended with an incomparably greater benefit for us, but in general there was little connection in the actions of the troops. The field marshal, confident of success, remained with the guard and did not see it with his own eyes; private bosses gave orders arbitrarily. A huge number of our cavalry close to the center and on the left wing seemed more assembled for the parade, showing off their harmony more than their speed of movement. It was possible to prevent the enemy from uniting his scattered infantry, to bypass and stand in the way of his retreat, for there was a considerable space between his camp and the forest. The enemy was given time to gather troops, bring in artillery from different sides, reach the forest unhindered and retreat along the road running through it through the village of Voronovo. The enemy lost 22 guns, up to 2,000 prisoners, the entire convoy and crews of Murat, King of Naples. Rich carts were a tasty bait for our Cossacks: they took up robbery, got drunk and did not think of preventing the enemy from retreating.”

Thus, the main objective The battle was not fully achieved, but its result was still quite successful. This concerned, first of all, raising the spirit of the Russian troops. Also, before this, throughout the entire War of 1812, in not a single battle did any of the sides (even at Borodino) have such a number of captured guns - 36 (according to other sources, 38) guns.

As for the losses of the parties, Kutuzov, in a letter to Emperor Alexander I, reported 2,500 killed Frenchmen and 1,000 prisoners. The Cossacks took another 500 prisoners the next day during the pursuit. The commander-in-chief estimated the losses of the Russian side at 300 killed and wounded.

Military theorist Clausewitz confirmed French losses of 3-4 thousand soldiers. Two of Murat’s generals, Dery and Fischer, were killed in the battle. The day after the battle, Russian posts received a letter from Murat asking them to hand over the body of General Deri, the head of his personal guard. This request could not be satisfied because the body could not be found.

It is necessary to point out that the military historian Bogdanovich provided a list of losses Russian army, where 1,200 people were listed (74 killed, 428 wounded and 700 missing). According to the inscription on the marble slab on the wall of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, the losses in killed and wounded amounted to 1,183 people.

Alexander I generously rewarded his military leaders: Kutuzov received a golden sword with diamonds and a laurel wreath, Bennigsen received diamond insignia of the Order of St. Andrew the First-Called and 100 thousand rubles. Dozens of other officers and generals received awards and regular promotions. As after the Battle of Borodino, the lower ranks, participants in the battle, received 5 rubles per person.

The described inconsistency of actions on the field of the Tarutino battle caused an aggravation of the long-standing conflict between Kutuzov and Bennigsen. The latter reproached the commander-in-chief for refusing support and withdrawing Dokhturov’s corps from the battlefield. The result of this confrontation was Bennigsen's removal from the army. As Kutuzov wrote to his wife in a letter dated October 30, 1812: “I hardly allow Bennigsen to visit me and will soon send him away” (which was ultimately done).

Most likely, it was the battle near Tarutino that pushed Napoleon to retreat from Moscow. In his notes, Roos indicated: “this ... camp on the Chernishna River, near the village of Teterinki, where our division and I stood with the last remnant of our regiment, was the final point of our difficult campaign deep into Russia, and October 18 was the day when we were forced were about to start retreating."

Accordingly, despite the fact that the decision to withdraw was made by Napoleon before the start of the Battle of Tarutino, it was after receiving news of this battle that he finally made the decision to leave Moscow. And the very next day the French retreat began towards Kaluga.

It is interesting that in memory of the Tarutino victory over the French, the owner of Tarutino, Count S. Rumyantsev, freed 745 peasants from serfdom in 1829, obliging them to erect a monument on the battlefield.

As already indicated, Napoleon initially planned to spend the winter in Moscow: “There was a moment,” noted the French officer Bosset, “when the emperor thought to spend the winter in Moscow; we collected a significant amount of provisions, which were replenished daily by the discoveries that the soldiers made in the cellars of the burned houses... In the cellars we found whole piles of all kinds of things, flour, pianos, hay, wall clocks, wines, dresses, mahogany furniture, vodka, weapons, woolen materials, beautifully bound books, furs at different prices, etc. And the churches were overflowing with things. Napoleon was so determined to spend the winter in Moscow that one day at breakfast he ordered me to make a list of artists from the Comédie Française who could be called to Moscow without disrupting the performances in Paris.”

As already mentioned, on October 4 (16), Napoleon sent the Marquis Lauriston, who was ambassador to Russia just before the war, to Kutuzov’s camp. Soviet historian E. Tarle wrote: “Napoleon wanted, in fact, to send General Caulaincourt, Duke of Vicenza, too former ambassador in Russia even before Lauriston, but Caulaincourt persistently advised Napoleon not to do this, pointing out that such an attempt would only indicate to the Russians the uncertainty of the French army. Napoleon became irritated, as always, when he felt the justice of the argument of someone arguing with him; and he was already very unaccustomed to debaters. Lauriston repeated Caulaincourt’s arguments, but the emperor interrupted the conversation with a direct order: “I need peace; as long as honor is saved. Immediately go to the Russian camp”….Kutuzov received Lauriston at headquarters, refused to negotiate with him about peace or an armistice and only promised to bring Napoleon’s proposal to the attention of Alexander.”

It is interesting that Kutuzov decided to take advantage of Lauriston’s visit to create an impression on him of the high morale of the army. The Russian commander-in-chief ordered to light as many fires as possible, give the soldiers meat for dinner, and sing at the same time.

During this meeting, Lauriston categorically denied the involvement of the French in the fire in Moscow and reproached the Russian soldiers for excessive cruelty. But Kutuzov insisted that Moscow was plundered by the enemy, and the fire was also the work of the marauders of the Great Army. The meeting ended with Kutuzov assuring Lauriston that he personally would never enter into peace negotiations with the French, because he would be “cursed by posterity for the very possibility.” But he promised to convey Napoleon’s peace proposals to Alexander I. Although Lauriston sought permission to go to St. Petersburg himself, the next morning Prince Volkonsky was sent to the Russian Emperor with a report on the meeting.

Alexander I expressed dissatisfaction with the fact that Kutuzov, despite his order not to enter into any negotiations with the French, nevertheless accepted Loriston. But the field marshal most likely entered into negotiations solely with the goal of gaining additional time to bring the army into combat readiness. He understood perfectly well that every day his army was growing stronger in the Tarutino camp, and the Great Army was disintegrating in Moscow. As it turned out, Kutuzov’s calculation completely justified itself: Napoleon waited in vain for several more days for an answer from Alexander I. But, as you know, the Russian emperor once again left this proposal unanswered, which became the last.

When the futility of concluding peace agreements with the Russian emperor and the impossibility of providing food for the troops finally became clear, Napoleon decided to leave Moscow. This was also facilitated by sharply deteriorating weather with early frosts. In addition, the Tarutino battle showed that Kutuzov had strengthened himself, and further clashes could be expected at the initiative of the Russian army. Baron Dedem wrote: “Spending the winter in Moscow was unthinkable. We made our way to this city, but not a single one of the provinces we passed through was conquered by us.”

Soon Napoleon gave the order to Marshal Mortier, who he appointed Moscow governor-general, to set fire to wine shops, barracks and all public buildings in the city, with the exception of the Orphanage, before leaving Moscow. An order was also given to set fire to the Kremlin palace and Kremlin walls. It was planned that the explosion of the Kremlin would follow the exit of the last French troops from the city.

On October 7 (19), the army moved from Moscow along the old Kaluga road. Only the corps of Marshal Mortier remained in the city. A bad feeling did not leave the French soldiers as they left Moscow: “There was something gloomy in this campaign. The darkness of the night, the silence of the soldiers, the smoking ruins that we trampled under our feet, and each of us anxiously anticipated all the troubles of this memorable retreat. Even the soldiers understood the difficulty of our situation; they were gifted with both intelligence and that amazing instinct that distinguishes French soldiers and which, forcing them to weigh danger on all sides, seemed to double their courage and give them the strength to look danger in the face.”

The convoy train of the retreating French army made a particular impression on the eyewitness. Christopher-Ludwig von Jelin recalled and was surprised: “But what a terrible picture the Grand Army now presented: all the soldiers were loaded with a wide variety of things that they wanted to take from Moscow - perhaps they hoped to take them to their homeland - and at that At the same time, they forgot to finally stock up on the essentials for the duration of their long journey. The convoy looked like a horde, as if it had come to us from foreign, unfamiliar countries, dressed in a wide variety of dresses and having the appearance of a masquerade. This convoy was the first to disrupt order during the retreat, since each soldier tried to send the things he had taken in Moscow ahead of the army, so as to consider them safe.”

Immediately after the start of the retreat, Napoleon planned to attack the Russian army and, having defeated it, get into areas of the country that were not devastated by the war in order to provide his soldiers with food and fodder. But, staying for several days in the village of Troitsky on the banks of the Desna River, he abandoned his original plan - to attack Kutuzov, since in this case he would have to withstand a battle similar to Borodinsky.

After this, Napoleon decided to turn right from the old Kaluga road and, bypassing the Russian army, go out onto the Borovskaya road. Next, he planned to move the army to places untouched by the war in the Kaluga province to the southwest, to Smolensk. He intended to calmly walk through Maloyaroslavets and Kaluga to Smolensk, spend the winter in Smolensk or Vilna and then continue the war.

In a letter to his wife dated October 10 (22), Napoleon wrote: “I left Moscow, ordering the Kremlin to be blown up.” This order had been sent to Marshal Mortier the evening before. The latter, having completed it, had to immediately join the army with his corps. But due to lack of time, Mortier did not have time to thoroughly prepare for the explosion of the Kremlin.

One of the local workers, who was forced to dig tunnels for explosives, recalled: “The French took me there, and they brought many other workers from our group and ordered us to dig tunnels under the Kremlin walls, under the cathedrals and the palace, and they dug themselves right there. But we just didn’t raise our hands. Let everything die, but at least not by our hands. Yes, it was not our will: no matter how bitter it is, dig. The damned ones are standing here, and when they see that one of us is not digging well, they now hit us with rifle butts. My whole back is beaten up.”

When Mortier set out from Moscow, explosions of planted mines began behind him: “Undressed, wounded by fragments of glass, stones, iron, the unfortunate ones ran out into the streets in horror. Impenetrable darkness enveloped Moscow; The cold autumn rain fell in torrents. Wild screams, squeals, and groans of people crushed by falling buildings were heard from everywhere. Calls for help were heard, but there was no one to help. The Kremlin was illuminated by the ominous flames of the fire. One explosion followed another, the earth did not stop shaking. Everything seemed to resemble the last day of the world.”

As a result, only the Vodovzvodnaya Tower was destroyed to the ground; the Nikolskaya, 1st Bezymyannaya and Petrovskaya towers, as well as the Kremlin wall and part of the arsenal, were severely damaged. The Faceted Chamber was burned by the explosion. Contemporaries noted that the attempt to undermine the most high building Moscow, Ivan the Great Bell Tower. It remained unharmed, unlike later extensions: “The huge extension to Ivan the Great, torn off by the explosion, collapsed next to it and on its feet, and it stood as majestically as the one just erected by Boris Godunov to feed workers in times of famine, as if mocking over the fruitless fury of the barbarism of the 19th century."

After the withdrawal of French troops from Moscow, the cavalry vanguard of the Russian army under the command of A. Benckendorff entered the city. He wrote on October 14 to M. Vorontsov: “We entered Moscow on the evening of the 11th. The city was given over to the plunder of the peasants, of whom a great multitude flocked, all of them drunk; The Cossacks and their elders completed the rout. Entering the city with the hussars and Life Cossacks, I considered it my duty to immediately take command of the police units of the unfortunate capital: people were killing each other in the streets, setting houses on fire. Finally everything calmed down and the fire was put out. I had to fight some real battles.”

A. Shakhovskoy also wrote about the presence in the city of crowds of peasants who ran to plunder it from all over the area: “The peasants near Moscow, of course, are the most idle and quick-witted, but at the same time the most depraved and selfish in all of Russia, confident in the enemy’s exit from Moscow and relying to the turmoil of our entry, they arrived in carts to seize what was not plundered, but gr. Benckendorff calculated differently and ordered the bodies and carrion to be loaded onto their carts and taken out of the city, to places convenient for burial or extermination, thereby saving Moscow from the infection, its inhabitants from peasant robbery, and the peasants from sin.”

A. Bulgakov, an official for special assignments under Count Rostopchin, described his first thoughts upon seeing Moscow: “But God, what I felt with every step forward! We drove through Rogozhskaya, Taganka, Solyanka, Kitay-gorod, and there was not a single house that was not burned or destroyed. I felt cold in my heart and could not speak: every face I came across seemed to beg for tears about the fate of our unfortunate capital.”

There were many destroyed houses: “From Nikitsky to Tverskaya Gates along left side everything was burned, and on the right - the prince’s houses were intact. Shcherbatova, gr. Stroganova and two more houses... Tverskaya from the Tverskaya Gate to the house of the commander-in-chief, on both sides, is all intact; and then, from Chertkov down to Mokhovaya, everything burned out, on both sides...” At the same time, the German settlement suffered greatly, “a vast field was formed, covered with burnt pipes, and when the snow falls, they will look like tombstones, and the whole quarter will turn into cemetery". Although among Muscovites there was talk about the miraculously surviving houses: “The arsenal was blown up, the wall near the Nikolsky Gate was also destroyed, the tower itself was destroyed, and among these ruins not only the image survived, but also the glass and the lantern in which the lamp is located. I was amazed and could not tear myself away from this spectacle. It’s clear that the only thing in town is about these miracles.”

From the data of the Moscow Chief of Police Ivashkin, one can learn about the number of human corpses taken from the streets of Moscow - 11,959, as well as horse corpses - 12,546. Most of the dead were wounded soldiers of the Russian army left in the city after the Battle of Borodino.

After returning to the city of Rostopchin, it was ordered not to arrange property redistribution and to leave the stolen property to those into whose hands it fell. Having learned about this order, people rushed to the market: “On the very first Sunday, mountains of looted property blocked a huge square, and Moscow poured into an unprecedented market!”

Despite all the problems of the city described, the departure of French troops from Moscow and the return of the Russians had a huge psychological impact on both the population and the imperial court. The Empress's maid of honor R. Sturdza wrote in her memoirs: “How can we describe what we experienced at the news of the cleansing of Moscow! I was waiting for the Empress in her office when this news captured my heart and head. Standing at the window, I looked at the majestic river, and it seemed to me that its waves were somehow rushing more proudly and solemnly. Suddenly a cannon shot was heard from the fortress, the gilded bell tower of which was located just opposite the Kamennoostrovsky Palace. This calculated, solemn firing, which marked a joyful event, made all my veins tremble, and I have never experienced such a feeling of living and pure joy. I would not have been able to bear such excitement any longer if the streams of tears had not relieved me. I experienced in those moments that nothing shakes the soul more than the feeling of noble love for the fatherland, and this feeling then took possession of all of Russia. The dissatisfied fell silent; the people, who had never given up hope for God’s help, calmed down, and the sovereign, confident in the capital’s state of mind, began to prepare to leave for the army.”

The same M. Volkova, who greeted the news of Kutuzov’s decision to leave Moscow with such incomprehension, wrote: “The French left Moscow... Although I am convinced that only the ashes of the dear city remain, I breathe more freely at the thought that the French do not walk in sweet spots dust and do not defile with their breath the air we breathed. There is general unanimity. Although they say that the French left voluntarily and that their removal was not followed by the expected successes, from that time on we all became emboldened, as if a heavy burden had been lifted from our shoulders. The other day, three runaway peasant women, ruined like us, pestered me on the street and did not give me peace until I confirmed to them that truly there was not a single Frenchman left in Moscow. In churches they again pray earnestly and say special prayers for our dear Moscow, whose fate concerns every Russian. You cannot express the feeling we experienced today, when after mass we began to pray for the restoration of the city, asking God to send a blessing to the ancient capital of our unfortunate Fatherland. The merchants who fled from Moscow are going to return there along the first sleigh route, see what happened to it, and, to the best of their ability, restore what was lost. One can hope to look at dear places that I tried not to think about, believing that I would have to forever give up the happiness of seeing them again. ABOUT! How dear and sacred is the native land! How deep and strong is our affection for her! How can a person sell for a handful of gold the welfare of the Fatherland, the graves of ancestors, the blood of brothers - in a word, everything that is so dear to every creature gifted with soul and mind?

From the book Stories of Simple Things author Stakhov DmitryAnd in the morning they woke up. You can’t trust the opinion of a person who hasn’t had a hangover! Venedikt Erofeev. Moscow - Petushki Hangover! There is so much in this sound... It happens that when we wake up the next morning, we hardly recognize the world, your loved ones, yourself. But what

From the book History of the Russian Army. Volume two author Zayonchkovsky Andrey MedardovichAbandonment of Moscow Guerrilla war Tarutino battle Retreat of Kutuzov's army to Moscow? Military council in Fili? Leaving Moscow? Napoleon's entry into Moscow? The transition of the Russian army to the old Kaluga road? Emperor Alexander I's plan for further

From book Napoleonic Wars author Sklyarenko Valentina MarkovnaTarutino March, or Kutuzov’s secret maneuver Kutuzov’s strategic plan after the Battle of Borodino was clear. He decided to retreat a very short distance and for a very short time. He needed to replenish and form a new army from the remaining units

From the book Napoleon and Marie Louise [other translation] by Breton GuyCAROLINE, IN ORDER TO SAVE THE NEAPOLITAN THRONE, ENCOURAGES MURAT TO TREAT THE EMPEROR “She had Cromwell’s head on the shoulders of a beautiful woman.” Talleyrand Napoleon was very superstitious. At the beginning of April 1813, he first felt that his fate was not

From the book Stalin against Trotsky author Shcherbakov Alexey Yurievich“It’s just that early in the morning there was a coup in the country” There is no point in talking in detail about the October Revolution - I outlined these events in another book, it’s not interesting to repeat. I will note only the main events important for the topic of this work. The Bolsheviks headed for

From Yusupov's book. Incredible story by Blake SarahChapter 13 Boris Nikolaevich. “They knew how to manage...” After the death of Prince Nikolai Borisovich Yusupov, his direct heirs were his wife Tatyana Vasilievna and his only legitimate son, Prince Boris Nikolaevich Yusupov, who lived his entire life in St. Petersburg and his family

From the book Ancient America: Flight in Time and Space. Mesoamerica author Ershova Galina Gavrilovna From the book Beneath Us Berlin author Vorozheikin Arseniy VasilievichThe dead serve the living 1 The regiment was replenished with new fighters. Even the Yaks, which were beaten during the attack on the airfield, were ordered to be left alone for now: why, at such a tense time for the front, should they bother repairing old ones when there are enough new vehicles. Just fight. But here

From the book Cossacks against Napoleon. From Don to Paris author Venkov Andrey VadimovichCavalry units of the Grand Army in 1812 under the general command of Murat Guards cavalry of Marshal Bessières: 27 squadrons, 6000 people; 1 Nansouty corps: 2 cuirassier and 1 light divisions, 60 squadrons - 12,000 people; II Corps Montbrun (later Sebastiani): 2 cuirassier and 1st light divisions, 60

From the book Stories about Moscow and Muscovites at all times author Repin Leonid Borisovich From the book Stalin in life author Guslyarov Evgeniy“He came out of this hell alive...” According to vague reports, he allegedly suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis, which, however, did not prevent him from making an adventurous escape from exile and overcoming the incredible difficulties of walking through the endless icy expanses of Siberia. In February

author Nersesov Yakov NikolaevichChapter 27 Tarutino maneuver: how it happened... Kutuzov understood that a retreat from Moscow was a trap for the enemy. While he is plundering Moscow, the Russian army will rest, be replenished with militia and recruits, and will wage the war against the enemy in its own way! He himself, as always, is very

From the book The Genius of War by Kutuzov [“To save Russia, we must burn Moscow”] author Nersesov Yakov NikolaevichChapter 29 Tarutino “bell” to Bonaparte The plan of the operation - usually called Tarutino (in French historiography - the battle of Vinkovo or on the Chernishna River) - was developed by Quartermaster General K. F. Tol, one of the main favorites of Mikhail Illarionovich. His

From the book Myths and mysteries of our history author Malyshev VladimirDead or Alive Alas, Bokhan was not the only traitor. In 1986, just a year after his disappearance, Viktor Gundarev, deputy KGB resident in Athens, fled to the West. Thus, our glorious scouts established in Greece a kind of “world

Tarutino maneuver of the Patriotic War of 1812 - important stage on the way to victory over Napoleon's army. The Tarutino march-maneuver of the Russian army - from Moscow to the village of Tarutino, located on the Nara River, 80 kilometers southwest of Moscow - was carried out from September 17 to October 3 (from September 5 to 21, old style) 1812.

After the Battle of Borodino, it became obvious that it was impossible to hold Moscow with the remaining forces without replenishment of reserves. Then the commander-in-chief of the Russian army, General Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov, outlined a plan. It was necessary to break away from the enemy and take a position that would cover Russian supply bases in Tula and Kaluga and threaten the operational line of Napoleonic troops, in order to gain time and create conditions for launching a counteroffensive.

On September 14 (2 according to the old style), leaving Moscow, Russian troops headed to southeast along the Ryazan road. On September 17 (5, old style), after crossing the Moscow River at the Borovsky Bridge, Kutuzov, under the cover of the rearguard of Lieutenant General Nikolai Raevsky, secretly from the enemy, turned the main forces of the army to the west. The Cossacks of the rearguard managed to carry away the vanguard of the French army with a demonstrative retreat to Ryazan.

On September 19 (7 old style), the Russian army arrived in Podolsk, and two days later - in the area of the village of Krasnaya Pakhra, where it camped, closing the Old Kaluga Road.

The vanguard of Infantry General Mikhail Miloradovich and Raevsky’s detachment were advanced towards Moscow, and detachments were allocated for partisan operations.

Having lost sight of the Russian army, Napoleon I sent strong detachments along the Ryazan, Tula and Kaluga roads to search for it.

On September 26 (September 14, old style), the cavalry corps of Marshal Joachim Murat discovered Russian troops in the Podolsk region. Subsequently, Kutuzov secretly (mostly at night) withdrew the army along the Old Kaluga Road to the Nara River.

The skillfully organized and carried out Tarutino maneuver allowed the Russian army to break away from the enemy and occupy an advantageous strategic position, which ensured its preparation for a counter-offensive. As a result of the maneuver, Kutuzov maintained communication with the southern regions of Russia, which made it possible to strengthen the army, cover arms factories in Tula and the supply base in Kaluga, maintain contact with the 3rd Reserve Observation Army of cavalry general Alexander Tormasov and the Danube Army of Admiral Pavel Chichagov.

The Tarutino maneuver demonstrated Kutuzov’s leadership talent and his art of strategic maneuver.

(Additional

By the beginning of October 1812, the Russian army was quite ready to launch a counteroffensive. The Russian command monitored the enemy’s actions and waited for an opportune moment. Mikhail Kutuzov believed that the French army would leave Moscow in the near future. Intelligence data gave reason to assume that Napoleon would soon take active action. However, the enemy tried to hide his intentions and made false maneuvers for these purposes.

The first signs of unusual enemy movement appeared in the evening of October 3 (15). General Ivan Dorokhov reported on the possibility of enemy movement towards Kaluga. True, on the same day, the chiefs of the partisan detachments, Alexander Figner, who was operating near Mozhaisk, and Nikolai Kudashev from the Ryazan road, reported that there was no reason for concern. However, Dorokhov's message alerted the commander-in-chief. He ordered the commanders of the army guerrilla units to strengthen surveillance in order to obtain more accurate information about the enemy and not miss his movements.

Mikhail Kutuzov knew that Napoleon, having occupied Moscow, found himself in a difficult position. The French army could not fully provide itself with everything it needed in Moscow. The command of the Russian army launched a widespread guerrilla war, which prevented the normal supply of troops. To search for food and fodder, the French command had to send significant detachments, which suffered losses. To protect communications and collect provisions, Napoleon was forced to maintain large military formations far beyond the borders of the ancient Russian capital. Napoleon's attempts to begin peace negotiations with Alexander and Kutuzov failed. The time for a decision to withdraw the army from Moscow was quickly approaching.

The generals of the Russian army perceived the news of the possible movement of the enemy from Moscow as the beginning of the retreat of Napoleon's troops. Quartermaster General Karl Toll proposed his plan for an attack on Murat's vanguard, which was supposed to significantly weaken the French army. The implementation of this goal, according to Tol, did not present any particular difficulties. Murat's vanguard could only receive reinforcements from Moscow; the opportunity arose to defeat a significant part of the French army separately from the main forces. According to reconnaissance data on the Chernishna River (a tributary of the Nara) 90 km from Moscow, Murat’s forces had been stationed there since September 24, observing the Russian army, there were no more than 45-50 thousand people. And, most importantly, the enemy settled down at ease and poorly organized the security system. In reality, under the command of Murat there were 20-26 thousand people: Poniatowski’s 5th Polish Corps, 4 cavalry corps (or rather, all that was left of them; after the Battle of Borodino, the French command was unable to restore its cavalry). True, the French vanguard had strong artillery - 197 guns. However, according to Clausewitz, they “were rather a burden to the avant-garde than they could be useful to it.” The front and right flank of the extended disposition of the forces of the Neapolitan king were protected by the Nara and Chernishna rivers, the left wing went out into the open, where only a forest separated the French from the Russian positions. For about two weeks, the positions of the Russian and French armies were adjacent.

It turned out that the left flank of the French, abutting the Dednevsky forest, was actually not guarded. Tol’s opinion was joined by the Chief of the Army General Staff Leonty Bennigsen, the general on duty under the Commander-in-Chief Pyotr Konovnitsyn and Lieutenant General Karl Baggovut. Mikhail Kutuzov approved the idea and decided to attack the enemy. That same evening, he approved the disposition, according to which the movement of troops was to begin the next day - October 4 (16), at 18 o'clock, and the attack itself was to begin at 6 o'clock in the morning on October 5 (17).

On the morning of October 4 (16), Konovnitsyn sent an order to the chief of staff of the 1st Western Army, Ermolov, which confirmed that the performance would take place “today at 6 o’clock in the afternoon.” However, the troops did not move out that day, since the disposition was not delivered to the units on time. Mikhail Kutuzov was forced to cancel the order. Apparently, the responsibility for the failure to timely deliver the disposition to the troops lies with Bennigsen, who was entrusted with command of the troops of the right flank, he did not check the receipt of the order by the corps commanders, as well as Ermolov, who was hostile to Bennigsen and did not check the implementation of the instructions. In addition, there was another reason that forced the command to cancel the performance. On the night of October 5 (17), Kutuzov received information about the beginning of the movements of enemy forces along the Old and New Kaluga roads. The commander-in-chief suggested that the French army had left Moscow and might end up at Tarutin at the time of the battle with Murat’s vanguard. Not wanting to meet the main forces of the enemy in unfavorable conditions, Kutuzov canceled the attack. Then it turned out that this information turned out to be false and the commander-in-chief scheduled the offensive for October 6 (18).

Battle plan

The Russian headquarters assumed that the enemy forces amounted to 45-50 thousand people and consisted of the cavalry corps of Murat, the corps of Davout and Poniatovsky. The main forces of the Russian army were sent to attack the reinforced vanguard of Marshal Murat. The army was divided into two parts. The right wing under Bennigsen included the 2nd, 3rd, 4th infantry corps, 10 Cossack regiments, and parts of the 1st cavalry corps. The left wing and center, under the command of the chief of the vanguard of the Main Army, Mikhail Miloradovich, included the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th infantry corps and two cuirassier divisions.

The 2nd, 3rd, 4th cavalry corps, Cossack regiments under the leadership of Major General Fedor Korf, were located in front of the left flank. The headquarters of the commander-in-chief was also to be located on the left flank. The main blow was to be delivered by the troops of Bennigsen’s right wing on the enemy’s left flank. Bennigsen divided his forces into three columns and a reserve. The first column was made up of cavalry under the command of Vasily Orlov-Denisov: 10 Cossack regiments, one horse-jaeger regiment, two dragoon regiments, one hussar regiment, one uhlan regiment. Orlov-Denisov was supposed to go around the left flank of the French troops through the Dednevsky forest and reach their rear near the village of Stremilova. The second column consisted of the infantry of Baggovut's 2nd Corps. She received orders to attack the enemy's left wing from the front near the village of Teterino (Teterinka). The third column included the 4th Infantry Corps under the command of General Alexander Osterman-Tolstoy. The third column was supposed to line up with the second column and attack the center of the French troops, also located near the village of Teterino. The reserve included the 3rd Infantry Corps of Pavel Stroganov, the 1st Cavalry Corps of Pyotr Meller-Zakomelsky. The reserve had the task of assisting Baggovut's 2nd Infantry Corps.

At the same time, M.A.’s troops were supposed to hit the enemy. Miloradovich with the support of part of the forces of the Russian army under the command of Kutuzov himself. Their task was to pin down the enemy's right flank. The troops were positioned in two lines. According to the disposition in the first line, near the village of Glyadovo (Glodovo), there were units of the 7th and 8th Infantry Corps. Behind in the second line was the reserve (5th Corps). The 6th Infantry Corps and two cuirassier divisions were to leave Tarutino to the edge of the Dednevsky forest and act in the center, advancing in the direction of the village of Vinkova. Finally, the army partisan detachments of I.S. Dorokhov and Lieutenant Colonel A.S. Figner struck behind enemy lines, they were given the task of cutting off the retreat route of the enemy army. According to Mikhail Kutuzov’s plan, Russian troops were supposed to encircle and destroy the enemy vanguard. The plan was good, but its implementation depended on the synchronization of the actions of the Russian troops. Under the conditions of that time, at night and in a wooded area, it was very difficult to achieve this plan.

Progress of the battle

To carry out the maneuver, the commander-in-chief sent the author of the plan, Tol, to help Bennigsen, who carried out reconnaissance of the routes. However, in practice, neither Bennigsen nor Tol managed to carry out the maneuver as planned. Only the first column of Orlov-Denisov arrived at the appointed place in the village of Dmitrievskoye on time. The other two columns got lost in the night forest and were late. As a result, the moment of surprise was lost.

As soon as dawn came, Orlov-Denisov, fearing detection of his troops by the enemy, decided to launch an offensive. He hoped that other columns had already taken up positions and would support his attack. At 7 o'clock in the morning, the Cossack regiments attacked Sebastiani's cuirassier division. The Russian Cossacks took the enemy by surprise. Orlov-Denisov noted the feat of 42 officers of the Cossack regiments, who “always being among the hunters in front, were the first to cut into the enemy cavalry columns, knock them over and drive them to the infantry covering their batteries; when the enemy lined up and was preparing to attack, they, warning him, despising all the danger and horror of death, regardless of either grapeshot or rifle volleys, desperately rushed at the enemy, cutting into the ranks, killed many in place, and drove the rest in great confusion several miles." The enemy abandoned 38 guns and fled in panic. The Cossacks reached the Ryazanovsky ravine, along which the road to Spas-Kuplya ran, but here they were met by the cavalry of Claparede and Nansouty and pushed back.

While the enemy's left flank was crushed, in the center the French managed to prepare to repel the attack of Russian troops. When units of the 4th Corps of the third column reached the northwestern edge of the forest and began an attack on Teterinka, the French were ready for battle. In addition, at first only one Tobolsk regiment went on the offensive (the rest of the units had not yet left the forest), then it was joined by the 20th Jaeger Regiment from the Orlov-Denisov detachment. Finally, parts of Baggovut’s second column began to appear, which included Bennigsen. Having deployed the rangers at the edge, Baggovut led them into the attack, without waiting for the rest of the column’s troops to approach.

Russian rangers pushed back the enemy and captured the Ryazanovskoye defile (a narrow passage between hills or water barriers), along which was the retreat route of the French troops. Marshal Murat, realizing the danger of the situation, gathered troops and drove the rangers out of the ravine. Karl Fedorovich Baggovut died during this battle. Bennigsen took command of the column. He did not dare to attack with the forces at his disposal and began to wait for the arrival of the third column and reserve. Joachim Murat took advantage of the respite and, under the cover of artillery fire, withdrew the main forces, convoys and part of the artillery to Spas-Kupla.

Karl Fedorovich Baggovut.

The reserve, the 3rd Infantry Corps, finally joined the second column. According to the original plan, he was supposed to advance in the direction of the Ryazanovsky ravine. However, Bennigsen ordered Strogonov’s corps to support the 2nd Corps and act in the direction of the village of Teterinka. Later, units of the 4th Corps emerged from the forest and Bennigsen directed them to Murat’s central position. This was a grave mistake, since the enemy was already withdrawing his troops.

Thus, the blow to the original plan was delivered only by the forces of Orlov-Denisov and part of the troops of the third column of Osterman-Tolstoy. And yet this attack brought some success. The French batteries were suppressed by Russian artillery fire. Russian infantry knocked the enemy out of their positions and forced them to hastily retreat. The enemy retreat soon turned into a rout. The Cossack regiments of Orlov-Denisov and the cavalry of Miloradovich pursued the French to Voronov. The success could have been more significant if the main part of the troops of the right wing of the Russian army had acted more consistently.

The troops of the right flank of the Russian army did not take part in the battle at all. They were stopped by order of the commander-in-chief. Kutuzov suspended the movement of troops for several reasons. He received a package from Kudashev, which contained an order from Marshal Berthier to General Arzhan dated October 5 (17) to send them convoys and cargo to the Mozhaisk road and the transition of his division to the New Kaluga road to Fominsky. This indicated that the French army was leaving Moscow and was going to move towards Kaluga and Tula along the New Kaluga Road. Therefore, Mikhail Kutuzov decided not to bring his main forces into battle with Murat. On October 4 (16), Seslavin reported to the commander-in-chief that he had encountered significant enemy forces at Fominsky. After analyzing this information, Kutuzov began to suspect that Napoleon was beginning to move his main forces. He orders Dorokhov’s detachment, instead of moving to the rear of Murat’s vanguard, to return to the Borovskaya road. Dorokhov's detachment, which arrived at Fominsky on October 6 (18). Dorokhov met a large French force and asked for reinforcements. The commander-in-chief sent two regiments to him and ordered Dokhturov's 6th Corps, the Guards Cavalry Division and Figner's army partisan detachment to also move into this area. Thus, Mikhail Kutuzov created in advance on his left flank a group that could withstand the battle until the main forces of the Russian army arrived.

It was information about the movement of large enemy forces that forced the Russian commander to act so carefully in the Battle of Tarutino. Further active actions against Murat’s forces lost their former significance, and a more serious “game” began. Therefore, the Russian commander-in-chief rejected the proposals of Miloradovich and Ermolov to pursue the forces of Marshal Murat.

Result of the battle

The defeat of Murat's troops did not happen due to the command's blunders, both in planning the offensive and in the unclear execution of the plans by the troops. According to the calculations of the historian M.I. Bogdanovich, 5 thousand infantry and 7 thousand cavalry actually took part in the battle with the French.

However, despite the fact that Murat’s forces were not destroyed, significant tactical success was achieved in the Battle of Tarutino. The battle ended in victory and the flight of the enemy; large trophies and a significant number of prisoners strengthened the morale of the army. This private victory became the beginning of active offensive actions by the army of Mikhail Kutuzov.

38 guns were captured. The French army lost about 4 thousand killed, wounded and prisoners (of which 1.5 thousand were prisoners). The Russian army lost about 1,200 people killed and wounded.

Battle of Tarutino

and myths of the War of 1812

Bavarian artist Peter von Hess(1792 -1871) participated in campaigns against the French, being at the headquarters of the field marshal Karl-Philippa von Wrede(1767 - 1839), the painter captured many military scenes; later he created a number of paintings from military life in the era of 1812 - 1814, including “The Battle of Tarutino”. The Battle of Tarutino was part of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, named after the village of Tarutino in the Kaluga region, eight kilometers from which the battle took place on October 18, 1812, which became the turning point of the war. It was in the Battle of Tarutino that Russian troops under the command of General Levin August von Bennigsen defeated French troops under the command of a marshal Joachena Murat. The legend of our victory in the Battle of Borodino was created by overly patriotic historians in spite of real facts. We lost Borodino, which is being celebrated today in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior is not entirely clear to me. Most likely, this is the desire of our authorities to promote themselves and join in the mythological victory of Russian weapons in the Battle of Borodino.

Marshal Joachin Murat and the generalLevin August von Bennigsen

After the Battle of Borodino, Mikhail Kutuzov realized that the Russian army could not withstand another major battle and ordered the army to leave Moscow and retreat. He first retreated in a southeast direction along the Ryazan road, then turned west to the Old Kaluga road, where he set up camp in the village of Tarutino near Kaluga. Here the Russian army received rest and the opportunity to replenish material and manpower. Napoleon, having occupied Moscow, did not bring his entire army there. Large French military formations were located outside of Moscow; Marshal Joachin Mur's group reached the Chernishne River near Tarutin, 90 km from Moscow, and observed the Russian army. The opposing armies coexisted for some time without military clashes. The Russian troops were commanded by an ethnic German from Hanover, who did not even have Russian citizenship, Count Levin August von Bennigsen(1745 - 1826), cavalry general in Russian service. The French were under the command of a marshal Joachena Murat(1767 - 1815), for some reason the name of this commander was distorted and is more often written as Joachim Murat. On October 18, 1812, the Battle of Tarutino took place, which was won by Russian troops. But inconsistency on the battlefield caused an aggravation of the long-standing conflict between Kutuzov and Bennigsen, which led to the latter’s removal from the army. The victory at Tarutino was the first victory of the Russian troops after the defeat at Borodino; the success strengthened the spirit of the Russian army, which launched a counteroffensive.

Prince Peter Bagration (1765 - 1812) - Russian infantry general

After the Russian-French War of 1812, 200 years have passed; from our school years we are familiar with the words - Patriotic War and Borodino, Napoleon and Kutuzov, Barclay de Tolly and Bagration, Raevsky’s battery and Denis Davydov. And we are familiar with the legends about this war, which we accept as truth. For example, the myth that Kutuzov was the founder of partisan warfare, although the first partisan detachments began operating in the French rear almost a month before Kutuzov arrived at the army. True, already this year the ethnic Georgian Bagration fell out of the picture. Putin, listing the heroes of Borodino, did not name Bagration, or rather, he didn’t even name him that way, but the ass-lickers from the federal channels helpfully cut out this name. It is indecent for Georgians to be a hero of Russia! This is an echo of Russian aggression against Georgia, a war we unleashed, preparations for which have been going on since 2007.

Oh, how great, great he is in the field!

He is cunning, and quick, and firm in battle;

But he trembled as a hand was extended towards him in battle

With a bayonet God-rati-on.

© G. Derzhavin

Georgian prince, but Russian general,

An invincible husband, of which there are only a few,

He lived in Russia, and at the same time gave his life

For our Orthodox capital.

© G. Gotovtsev

Napoleon's retreat from Moscow, artist Adolph Northern, 1851

Apart from the notorious defeat in the Battle of Borodino, for 200 years now we have almost no other topics about the Russian-French War of 1812 and the Foreign Campaign of the Russian Army of 1813–1814. After all, in the first three months of the war alone, almost 300 military clashes of various sizes took place, from skirmishes to major battles. But this remains behind the scenes. One cannot raise one's hand to call this war patriotic. The myth of the people's war still circulates today, the concept Patriotic War in the sense of unity of all classes around the throne, they proposed back in tsarist times, in Soviet times it was replaced by the myth that the people and the army are united. But no people's war Of course it wasn't. Russian serfs did not suffer from any patriotism, they did not want to fight for the Tsar and the Fatherland, they joined the militia without any desire, escaping at the first opportunity, there were up to 70% of deserters. In the western provinces of Russia, Poles, Lithuanians and Belarusians often greeted French troops with bread and salt. And in Ruza, near Moscow, the Russians greeted Napoleon as a liberator. That did not stop armed peasants from robbing French convoys. However, they robbed Russian convoys with no less pleasure. Taking advantage of the anarchy, the peasants also actively robbed and burned the estates of their landowners.

General Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly,

artist George Dow, 1829

Another myth that we inherited from Soviet times is the partisan movement. It is believed that the guerrilla war behind French lines was launched on the orders of Kutuzov. But the real organizer of guerrilla warfare is the general Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly(1761 - 1818), Baltic German from Riga. Western historians consider him the architect of the strategy and tactics of scorched earth, cutting off the main enemy troops from the rear, depriving them of supplies and organizing guerrilla warfare in their rear. It's good that Putin was a spy in Germany and finds mutual language with Merkel, supplying gas to her country, therefore, unlike the Georgian Bagration, the German Barclay de Tolly has not yet been erased from the history of the War of 1812. It was this German who was the author of the concept of cutting off communications, Andreas Barclay de Tolly, back in July 1812, the first partisan detachment was created - a Special Separate Cavalry Detachment consisting of a dragoon and four Cossack regiments. The first Russian partisans - General Baron Ferdinand Winzengerode and Colonel Alexander Benkendorf, who would later become chief of the gendarmes. The partisans of 1812 were military personnel from temporary detachments, purposefully and organizedly created by the command of the Russian army, including for operations behind enemy lines. In fact, these are rangers or special forces, but they walked behind the French rear not at their own discretion, but to carry out command assignments. Stories about landowners creating partisan detachments from their peasants are a myth.